A fair chance for all: Where should we focus?

Table of contents

Foreword

E ngā maunga e tū ake rā, e ngā awa e rere ake rā, tēnā koutou. Ko te manawa whenua o aku mihi e rere nei ki a koutou nā koutou i whai wā ki te tuku mai i ō koutou whakaaro, i ō koutou kōrero nei, hei hāpai, hei whakakaha i tēnei mahi. E mihi atu ana, e whakamānawa atu ana, e ona atu ana.

I’d like to personally thank you for all the mahi you put into telling us where we should focus our inquiry into reducing persistent disadvantage.

We heard from over 1,000 people. This was the largest response the Commission has had and shows how much you care about improving the lives of those who live in Aotearoa. Consulting on our Terms of Reference was also a novel experience for the Commission, which is all part of us trying new ways to inform and interact with a wider group of New Zealanders.

Your feedback has made a difference. Your reflections and ideas have informed the Terms of Reference for our inquiry, which have now been approved by Cabinet. For example, we heard that you’re tired of a focus on the negatives, and people continually being seen as ‘broken’ or in need of ‘fixing’. Instead, we heard you want government and society to recognise and build on the strengths that exist within communities and whānau. We also heard that there has already been plenty of research into persistent disadvantage, and that what is needed now is action. This is reflected in the Terms of Reference.

You gave us lots of ideas that we’ll use to shape and inform the inquiry. You shared your views on what aspects of disadvantage need to be addressed, such as housing, education, the early years of a child’s life, support for mental health, and the ongoing impacts of racism and colonisation.

This document summarises the main messages that you gave us. We’re excited to now get underway on the next stage of this mahi, to help find ways to ensure all Kiwis get a fair chance in life. We’ll start releasing our research findings early in 2022, followed by our draft findings and recommendations around August 2022.

We will be seeking your thoughts, knowledge and reflections during our work and, in particular, around our draft recommendations. We look forward to further engagements and enlightening kōrero. In the meantime, our sincere thanks for your involvement.

Ganesh Nana

Chair, New Zealand Productivity Commission Te Kōmihana Whai Hua o Aotearoa

Purpose

In June 2021, the Government asked the Productivity Commission to prepare the Terms of Reference for a new inquiry into the drivers of persistent disadvantage within people’s lifetimes and across generations. During July and August, the Commission sought input from across Aotearoa to help shape the Terms of Reference. This document summarises the main messages from the feedback.

The submissions covered a huge range of issues; many more than can be properly investigated in one inquiry. We took into account everything people told us, and then considered how the Commission can best add value with its available time and resources. The Terms of Reference direct the Commission to focus on systems-level change.

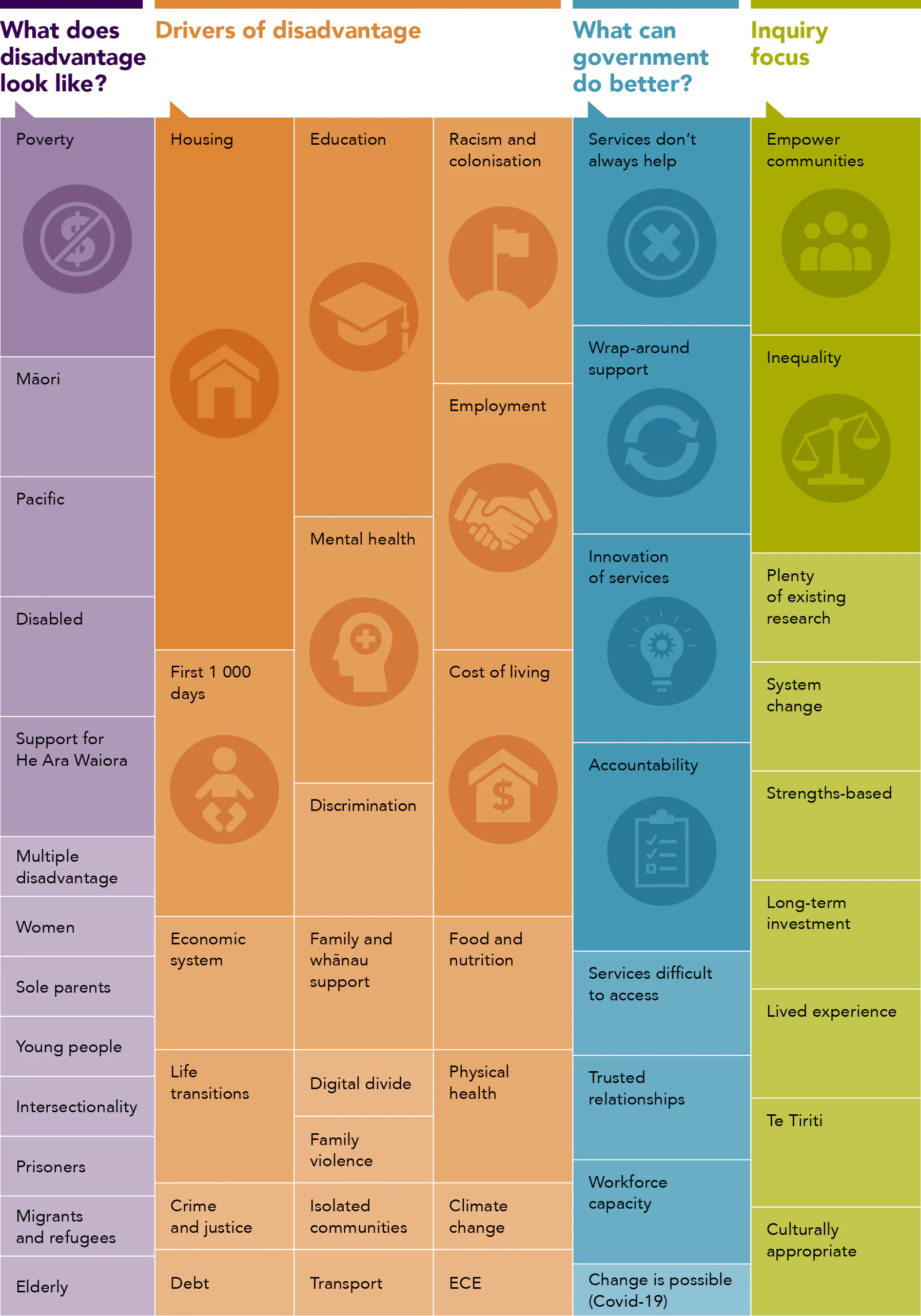

Figure 1 The most common themes from public feedback

The size of the square indicates the number of times each topic was mentioned.

Consultation process for a new inquiry

This was the first time the Commission has been asked by the Government to consult the public on a Terms of Reference.

The Commission released a consultation document and invited public input into where the inquiry should focus. We received 81 submissions and 875 responses to our online survey. We also spoke with over 180 people, including representatives from more than 60 organisations. In addition, Haemata facilitated four deep-dive online hui with a range of iwi and Māori. Details on these hui are set out in a separate report from Haemata. A summary of the high-level themes from the online survey responses are in a report by Text Ferret.

In total, over 1 000 people had their say. This is a record for the Commission, and we are extremely grateful to everyone who took the trouble of sharing their experiences and perspectives with us.

How your feedback made a difference

The Commission used the feedback to help develop the Terms of Reference for the inquiry, which was approved by Cabinet on 20 December 2021. For example, the Terms of Reference acknowledge the significant existing evidence base, and directs the Commission to bring together and build on this previous work. It also directs us to draw on the lived experience of the diversity of people who are affected by, and who have overcome, persistent disadvantage.

Many people offered valuable insights about the underlying causes of persistent disadvantage, and ideas for how to solve these problems. We will continue to use the rich information and perspectives provided as we undertake the inquiry.

The inquiry will promote a strengths-based approach to developing recommendations that will help whānau and communities realise their potential and enhance their mana and wellbeing. This includes exploring ways to better support Māori-led and Pacific-led solutions.

1 What persistent disadvantage looks like

People provided a lot of rich information about what it is like to live in persistent disadvantage, and who is most likely to be affected.

Disadvantage is not just about income

Most submitters mentioned poverty in some form (eg, due to insufficient benefit levels, low pay and/or the high cost of living). However, many people also pointed out that persistent disadvantage is not just about low income or material hardship. Disadvantage can have multiple aspects, which are complex and often interrelated. The impacts of different facets of disadvantage are cumulative, and can result in toxic levels of stress for whānau and communities.

“Poverty, access to education, affordable housing, stable and quality income levels, community connection, level and quality of social supports in place (have someone I can count on), ability to be self (feel accepted and celebrated for being you), connection to nature and Whenua.”

The Commission’s consultation document proposed using the Treasury’s He Ara Waiora framework as a way of thinking about the multiple aspects of disadvantage. As a wellbeing framework, He Ara Waiora can be used to explore the range of barriers people may face to reaching their potential. The feedback showed widespread support for using this framework.

“I also believe having both meaningful opportunities no matter one’s capability, engagement and participation within one’s community, and a sense of belonging is essential for wellbeing.”

Who is affected by persistent disadvantage?

No one size fits all

People pointed out that those facing multiple barriers to reaching their potential are not a homogeneous group. Different people (as well as different whānau and communities) face a diverse range of issues, which means there is no magic bullet ‘programme’ that will work for everyone.

“No two individuals, whanau or communities are alike – every presentation of disadvantage will comprise a different mix of social problems, that have each occurred in different ways, at different times and had a different impact – there simply is no ‘one size fits all’.”

Groups to focus on

Most people suggested focusing on Māori, Pacific and disabled people (including neurodiverse) as those suffering most from persistent disadvantage.

“I didn’t realise I had a learning disability until struggling through 6 years of undergraduate [study] – I’m grateful for what I know now but I wish I knew sooner, that I had support throughout my life instead of thinking I was stupid.”

People also identified children and young people, sole parents, women, rural and isolated populations, prisoners, migrants and refugees, the elderly and the rainbow community as groups at higher risk of persistent disadvantage.

Many noted that people in persistent disadvantage often belong to more than one of these groups, for example, a young sole parent living in a rural area. They said the inquiry therefore needs to consider the cross-over (or ‘intersectionality’) of groups.

2 The drivers of persistent disadvantage

Submitters talked about various causes of disadvantage, the outcomes of living in persistent disadvantage and the protective factors that help people thrive. This section summarises the most commonly-mentioned factors as ‘drivers of disadvantage’. These shouldn’t be seen in isolation, as some people experience multiple drivers of disadvantage simultaneously.

Housing

Housing was the most frequently raised issue in the consultation. Many see housing as a fundamental human right and an important foundation to support wellbeing and allow people to participate in society.

“…having adequate, affordable and suitable housing is an essential pre-condition of wellbeing. Housing is foundational to enabling fair life chances. Without a secure home, people cannot carry on many of the fundamentals of life that enable them to engage in work and their community, keep themselves and their families healthy, and provide a platform for children’s development.”

People consistently told us that housing was no longer affordable for many people in New Zealand. They said that high house prices and rents are soaking up more of people’s income, which is contributing to higher costs of living and overcrowding.

“Housing is a big problem. Makes it hard to feed kids on minimum wage.”

Many people said that secure tenure is important for creating stability in people’s lives and the lives of their family and whānau.

“Insecure, unaffordable housing means people lose connection with their support networks, places they are familiar with and access to services. It frequently disrupts educational achievement and employment, both of which are essential to breaking the cycle of disadvantage.”

People also said that unhealthy homes are causing preventable illnesses, particularly for people in rented houses. They talked about lack of access to suitable housing, in particular to suit different cultures (eg, those living in large extended families) and for people living with a disability.

“There are not enough homes with accessible features beyond just a ramp – one level, bathrooms accessible for a wheel chair, open plan, grass in a yard for service animals, catering for family members living with the disabled person eg, a parent with children.”

Some also noted the extreme outcome of unaffordable housing is homelessness.

Education

Education was the second most frequently raised theme in our consultation. Many people told us that education can provide the opportunity to help people achieve the life they want.

“To achieve a healthy standard of living people need access to essential resources such as good quality food, transport, healthcare, and secure, warm housing. To access these resources without ongoing government assistance people need to be educated and skilled so they have a higher chance to gain employment and receive sufficient income.”

Yet as many people pointed out, New Zealand has some of the biggest differences in education outcomes attributable to socio-economic issues in the developed world.

“Education – huge inequity in outcomes for different subgroups of our population, and educational practices that perpetuate rather than address this disadvantage (eg, punitive discipline approaches, removal from school, systemic racism, streaming...).”

The key challenge raised by most people was that schools need additional resources to be able to support students facing barriers to reaching their potential, such as students with health problems, learning difficulties or neurodiversity. Another key point made was that education needs to be culturally appropriate, and that teachers must ensure their expectations of children are not biased by race.

“There are many disadvantaged tamariki in primary schools, who through no fault of their own, do not fit into or respond to the New Zealand education curriculum, often leading to truancy in secondary schooling.”

Some of the problems people raised about the education system included the lack of support for people leaving school without qualifications, the questionable value of some low-level tertiary qualifications, and difficulties in retraining given the changing nature of work. Students leaving school without basic skills (such as social skills, literacy and numeracy) also featured. Some people pointed out that the education system currently doesn’t equip all students with the necessary skills they need for life.

The impacts of racism and colonisation

For Māori, disadvantage is intertwined with the impacts of colonisation and racism. The story for Pacific peoples in New Zealand is different, but also has racism at its core. Many people are keen for the inquiry to tackle these difficult issues, and make recommendations for addressing systemic racism, as well as prejudice and a lack of cultural understanding in the way services (such as health, justice and education) are designed and delivered.

“The significant losses of land, resources and culture experienced by Māori as a result of colonisation have been carried throughout generations, contributing to cycles of intergenerational trauma and disadvantage for many. This disadvantage is further exacerbated by the modern structures and systems in New Zealand, largely operating under a Western model.”

In the hui facilitated by Haemata, Māori participants initially discussed issues like housing, education, mental health, drugs and alcohol, and food. Knowing where to go to access services was also raised as an issue; government systems are confusing for people not used to using them.

The facilitators in these sessions tried to find the issues underlying these ‘symptoms’. They found a lack of identity, disconnection from culture and an economic model that doesn’t work for Māori. These issues relate strongly to the Māori concepts of Tino Rangatiratanga and Mana Motuhake:

- Tino Rangatiratanga is a form of negative freedom – a person having an absence of barriers to achieving their potential; and

- Mana Motuhake is a form of positive freedom – a person having the resources to achieve their potential.

More information on these findings is available in the Haemata report.

First 1 000 days of a child’s life

There was a lot of agreement among submitters about the importance of a child developing a strong bond with a trusted adult in the first few years of life. This can have a huge impact on their future prospects and potentially avoid ongoing cycles of disadvantage for the next generation.

“Many tamariki/children who experience trauma and toxic stress early in life exhibit negative consequences as they get older and this can affect their capacity and capability to parent their own children and the cycle of disadvantage continues.”

Many people suggested a number of important protective factors that could help support children to deal with challenges later in life. These included helping children develop executive functioning skills (a set of mental skills that include working memory, flexible thinking and self-control), reducing exposure to adverse childhood experiences, and better supporting parents.

Many people explained that increased support for during pregnancy and the first few years of life are investments that will pay themselves back in the long term and are likely to be more effective than intervening later in life.

“…responsive relationship with adults is a key protective factor. Can intervene later but more expensive.”

Mental health

Many people identified mental health problems as an underlying driver of persistent disadvantage. They told us that unresolved trauma (often from adverse childhood experiences) frequently lies behind other issues like addiction and criminal behaviour.

“…persistent and intergenerational disadvantage is invariably underpinned by persistent intergenerational unresolved trauma.”

People said the main problems are a lack of mental health services and addiction support services. At the moment, the system is focused on people who have reached crisis point, which means that they often end up being harder and more expensive to treat than they would have been if help had been available earlier.

“Promotion of wellbeing and prevention of mental distress needs to start well before people need to access services or treatment. By assisting young people to pre-emptively build wellbeing, we can make effective interventions.”

Some people also mentioned the importance of wider factors, such as societal attitudes on mental health. In particular, submitters said there is stigma around poverty and mental health problems that leads to shame, exacerbating the issues people face.

Employment

Many people pointed to the availability of good-quality jobs as an important path out of poverty. They defined good-quality jobs as being meaningful, offering the living wage, and providing secure hours and opportunities for progression. Workers in some industries expressed a view that migrants were suppressing wages. Some people raised the precarious nature of work and uncertainty around hours; the so-called ‘gig economy’. A few people told us that jobs will need to be sustainable as the country moves to a low emissions economy.

“Although unemployment in Aotearoa is very low, many people are still living in poverty. This indicates wages are not keeping up with living costs, forcing some people to hold down several jobs and yet still be on a low overall income.”

Where you live

Where you live was raised by many people as a contributor to disadvantage. They explained that those living in disadvantaged communities are more likely to be exposed to negative influences, compared to people in less deprived communities.

“[T]hose living in [the] most deprived areas in New Zealand often have greater access to ‘bad’ environmental influences, such as gambling venues, takeaway shops, and liquor stores, than ‘good’ environmental influences, such as green spaces.”

People also said that the availability of government services (such as publicly-funded health services) can vary from place to place (the so-called ‘postcode lottery’). Good-quality jobs may be scarce in rural areas. Transport was also raised as a barrier in accessing services and jobs, especially the lack of public transport in rural areas.

Other drivers of disadvantage

People described a range of other drivers of disadvantage, and protective factors, including the following:

- Access to affordable, high-quality childcare and early childhood education to support a child’s first 1 000 days and enable sole parents to engage in meaningful work.

- The high cost of living. Housing costs are the key driver, but many people also said that other essentials such as food (especially healthy food for growing families), utilities and transport are too expensive.

- Crime and justice, in particular systemic racism impacting Māori. Some people also pointed out that minor offences (such as driver licensing and car registration) lead to many first jail terms.

- Debt, both with government but also with poorly-regulated private lenders.

- The digital divide, especially as government pushes more of its services online.

- Discrimination, including sexism, ageism and discrimination against LGBTQI.

- The economic system – neoliberalism, deregulation, the negative impacts of economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s. and the acceptance of a ‘natural’ rate of unemployment.

- Family and whānau support provides a significant source of valuable unpaid work and acts as a protective factor against disadvantage.

- Family violence and abuse is a risk factor for trauma and poor lifetime outcomes.

- Physical health, and in particular the availability of affordable dental treatment.

- Transitions between systems was mentioned as a point where people frequently fall through the cracks (eg, from midwife to a Well Child Tamariki Ora provider, early childhood education to school, and school to work or further study).

3 What government could do better

People described a range of ways in which government services could be improved, to better support whānau and communities to reach their potential.

For whānau and communities

Services can be difficult to access

A common theme was that it can be hard for people to find out about and locate the services that they are entitled to, and then to navigate the system to access them. In addition, individual services often only address part of a person’s needs, or only last for a limited time. It can also be extremely time-consuming to engage with services.

“It is exhausting dealing with the very agencies that have been set up to help people.”

Services don’t always help

Many people raised several issues about the welfare system (such as benefit payments being insufficient to meet the cost of living, and high abatement rates), which can keep people trapped in poverty as they start to earn. The punitive nature of eligibility requirements was also a common theme, in particular the outmoded treatment of relationships, and the use of child support to offset a Sole Parent’s Support payments. A Universal Basic Income or Guaranteed Minimum Income were suggested as potential solutions to these problems.

“More people on a benefit could work odd hours if the threshold was higher… it’s easier to NOT work, and have to deal with WINZ constantly...”

“[B]ringing government and community-based responses increasingly together grounded in a community-based, collective and relational way of working needs to be a focus of Government when it comes to addressing persistent disadvantage. This approach should focus on delivering outcomes that are genuinely responsive to family and whānau needs, and which enable solutions to address persistent disadvantage that are locally-grounded and encourage collaboration between service providers. People and whānau are best supported by integrated community services grounded in local communities and which are informed by the aspirations and needs of the whānau, hapū, Iwi, families, children and young people that they serve.”

Some people also felt that how they were treated by some government services made matters worse.

“It is awful to have to ask for help and [be] made to feel small for doing so.”

Services need to work together to provide wrap-around support

Delivering services in silos (eg, health, education, welfare) may work for most of the population, but fails those facing multiple disadvantages. People can fall through the cracks while transitioning between systems, further delaying access to the services they need. People said that services need to provide intensive, tailored, wrap-around support to help people who are dealing with multiple issues simultaneously. To do this, people suggested that government agencies need to work together, rather than providing funding in silos and expecting delivery agencies to coordinate themselves on the ground.

“…persistent intergenerational disadvantage is a complex problem and as such cannot be broken into its constituent parts or examined and responded to via silos.”

Services need to build trusted relationships

Many people raised the importance of trusted relationships in providing effective services. The barriers faced by people are complex, deeply personal and interrelated. Deep distrust of government exists in some communities, often stemming from the legacy of colonisation.

“Real change needs relationships.”

It was clear from the feedback that trusted relationships are needed to get to the heart of an issue and deliver lasting change in people’s lives.

Trusted relationships take time to build, which is difficult within the current system of short- term, contestable government contracts and siloed funding.

For service providers

Make it easier for providers to innovate and demonstrate what is working

Many providers said that it is too difficult to introduce new services or new ways of doing things because of the current approaches to accountability for funding, including data collection and evaluation. Service providers said they wanted longer-term contracts with funding that covered the full cost of services and that allows them to build their workforce capacity and capability. They also want less onerous reporting requirements. A key challenge is allowing delivery agencies greater flexibility to innovate while still maintaining accountability.

“…[t]he over reliance on ‘markets, measurement and management’… has concentrated power and control in Wellington based government institutions (that consume a large amount of resources) with an over focus on managing risk and reducing spending at the expense of innovation, supporting emerging ideas and informal agile community networks.”

Several people said that reform is needed in the way that data is shared, to enable services and communities to identify issues and demonstrate they are making a difference.

“Local communities need better access to local official data in planning and monitoring initiatives that address disadvantage.”

Government services need to be accountable

Many people said that services delivered by government agencies are rarely evaluated, while contracted services are required to be extensively audited and evaluated. Some also suggested that holistic measures (like subjective wellbeing or client satisfaction with the publicly- funded service) could be used more frequently.

Covid-19 demonstrated that change is possible

Several people pointed out that during the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown the government provided non-government organisations with the flexibility to deliver what was needed to their communities without the need to justify how every dollar was spent. There were also examples of government agencies working together during the initial Covid-19 response, but subsequently everyone ‘snapped back’ to business-as-usual operating models.

4 What the inquiry should focus on

While submitters pointed out various drivers of disadvantage, they also noted that people often experience multiple drivers at once. For that reason, many people suggested that the inquiry should not look at individual drivers in isolation. Instead, the inquiry could contribute to breaking the cycle of disadvantage by focusing on changing systems.

There is plenty of existing research

Many people pointed out that a lot of research has already been done dating back to the Royal Commission on Social Security in 1972 and Puao-Te-Ata-Tu, The Report of the Ministerial Advisory Committee in 1988. People mentioned more recent contributions, including the Welfare Expert Advisory Group, the Expert Advisory Group on child poverty and the Commission’s own inquiry More effective social services. Specific pieces of research were also mentioned, including Decades of disparity on Māori health disparities.

“We believe there is already sufficient evidence, knowledge and research to identify and outline key ways forward in reducing persistent disadvantage.”

People told us that it is important for the Commission to be clear on what added value this inquiry can bring to an already crowded space. Some recommended that the inquiry focus on bringing together existing research into a prioritised plan of action. This plan would need to consider why previous recommendations haven’t been actioned and how to remove barriers to change.

“[H]ow is it that urgent transformational change, required to break the cycle of disadvantage, has been unfailingly called for across inquires, reviews, and reports in New Zealand, for well over three decades, and that this change has failed to appear?”

Systemic change

Many felt that the inquiry needs to focus on the systems (inside and outside of government) to understand the drivers leading to persistent disadvantage and to identify where changes are needed to allow people to live free of disadvantage.

“Individuals, whānau and communities cannot break free from the cycle of disadvantage and thrive long-term unless there is a system to support and enable that to happen.”

Take a strengths-based approach

Many people pointed out that continual use of ‘deficit framing’ damages the mana of those facing multiple barriers in reaching their potential. For example, people don’t respond well to being seen as ‘broken’ and requiring ‘interventions’. Some people might be classed as ‘disadvantaged’ by statistics, but don’t view themselves that way. Instead of telling people what is wrong with them, it is important for government services to focus on building people’s strengths. Services are more likely to create change if they have the buy-in of the people involved and help create a positive vision of the future. Deficit framing is pervasive because it is used to collect data and target public funding. This critique was also applied to the framing of this inquiry and the Commission’s consultation document.

“[T]he focus of the inquiry [should] be on establishing a strengths-based vision for the future – one where all kiwis can thrive and designing a system that will enable that to be achieved.”

A few people felt that greater personal responsibility was needed, but a clear majority felt most people are doing the best they can in difficult circumstances.

Make the case for long-term investment

People stuck in persistent disadvantage represent lost opportunity. Some people suggested it would be useful for the inquiry to produce evidence to support long-term government investment in reducing persistent disadvantage. This is important because effective treatment (eg, healing from trauma) is expensive, can take many years, and there can be a long lag time between treatment and outcome.

“What are the economic benefits of reducing inequality (ie, if you spend $x now, you won’t have to spend $y later) – build the case for Treasury.”

This point was particularly raised in the context of the education system failing Māori and Pacific children. The ageing population and future demographic changes mean today’s Māori and Pasifika youth are the future workforce. Improving their outcomes is therefore critical for enhancing wellbeing, and lifting long-term economic performance and productivity.

Draw on lived experience

Some people emphasised that the ‘lived experience’ of people facing barriers to reaching their potential is just as valuable as quantitative research. In particular, understanding someone’s life can provide context; the ‘why’ behind some of the statistics in the existing research and government reports. Some felt more research about lived experience would be useful, while others pointed out that plenty of this work has already been done and just needs to be drawn together.

“To understand why the current system is not fit for purpose the inquiry will need to understand the life journeys of the most disadvantaged families and communities.”

A few people also recommended talking to front-line workers (eg, teachers, nurses, social workers).

Empower communities to support themselves

Many people said that the best way to tackle disadvantage is through empowering communities and whānau to help themselves, rather than via government agencies (who are seen as outsiders and engender low trust, partly because people have negative experiences of dealing with government in the past).

“Use and enhance the capacity, knowledge, wisdom and ability of local communities and community and voluntary organisations around the country that are working with and on persistent disadvantage.”

Communities and whānau already provide unpaid work for each other and are more likely to have the trusted relationships needed for services to be effective. They are also more likely to understand the issues faced by people in their community. Some people noted that this does not preclude the need for outside expertise to help solve problems. However, communities and whānau should be involved in decision-making. This will help ensure the services are effective and mana-enhancing.

“Empowering communities with specialist/ expert advisory committees and sufficient funding rather than regulating them and expecting them to comply.”

By Māori for Māori

Many people said that solutions for Māori should be designed and led by Māori. They pointed out that adopting this approach would not only improve the effectiveness of services, but would also help honour Te Tiriti. Some people also said similar things for Pacific communities.

“Recognise that State interventions, particularly for Māori, have harmed generations of Māori and identify ways that will stop this – Fund and support Māori-led groups and initiatives to restore people’s wellbeing – Look at preventative and strengthening community strategies and initiatives.”

Some people felt that communities have innovative solutions that can be scaled up, while others felt that it is impossible to scale these up because every community is different.

Inequality makes it harder to get ahead

Some people felt that it was difficult to focus on disadvantage without considering entrenched advantage, which includes wealth as well as social networks and connections (eg, in the labour market).

“The time has come for deep structural changes to systems, not tweaking minor fixes to the status quo. Lay the groundwork for creating an equitable society that does as much to pull unhealthy excess and wealth accumulation down as much as lifting persistent poverty up.”

Advantage can be passed intergenerationally in the same way that disadvantage can be (eg, through inheritances). The main point made was the lack of taxes on property and wealth, which also increases the incentive to speculate on housing, pushing prices up, though some also raised income taxes and wage inequality.