Close to one-fifth of New Zealanders experienced persistent disadvantage in both 2013 and 2018

Approximately one in five New Zealanders (18.2% or 697,000) experienced persistent disadvantage in one or more domains in both 2013 and 2018. Around one in twenty New Zealanders (4.5% or 172,000) experienced complex and multiple forms of persistent disadvantage (in two to three domains).

The most common persistent disadvantage experienced was being left out (8.8% or 337,000), followed by being income poor (7.4% or 283,000) and then doing without (6.9% or 265,000).

Persistent disadvantage is a systemic problem

A central finding of this inquiry is that people experiencing disadvantage and those trying to support them are constrained by powerful system barriers. Siloed and fragmented government and short-termism reflect well-known challenges that the public management system has been grappling with for decades. Outside the public management system, power imbalances, discrimination, and the ongoing impact of colonisation form part of the economic and social context and create the main drivers for both advantage and disadvantage in Aotearoa New Zealand.

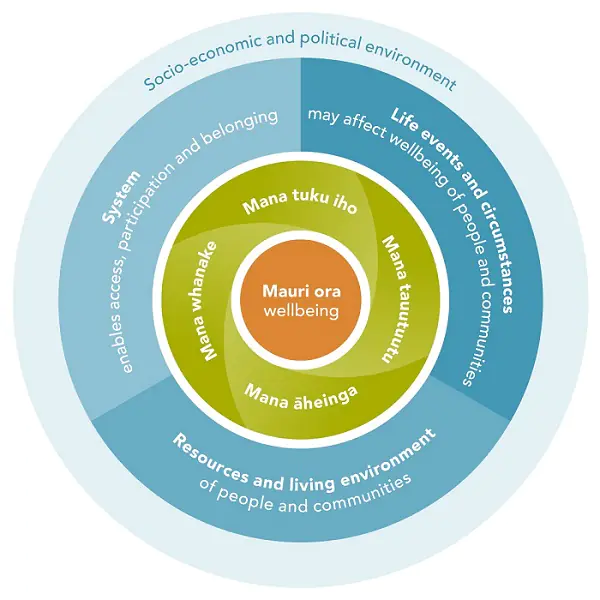

Social, economic, health and other conditions, along with life and past events can make people more vulnerable to persistent disadvantage. Support to manage or overcome these conditions might come from whānau, communities or the government, or from all these places. The goal for the system needs to be that all people can get what they need to live a better life.

Factors that protect against persistent disadvantage include adequate income, housing, health, and social connection; cultural identity and belonging; knowledge and skills; access to employment; stable families; and effective government policies and supports.

For many people, disadvantage does not persist. People can get themselves through a temporary period of disadvantage by drawing on their own resources, accessing support from family, whānau, and friends, the local community, and from the Government (central and local).

However, in the absence of effective support, disadvantage that would otherwise be temporary can persist and compound, trapping people within multiple complex disadvantages.

There are challenges with the way the current policy and public management system operates

In Aotearoa New Zealand, persistent disadvantage continues despite repeated reviews that describe consistent themes and call for changes in policymaking and service design. Although the advances in wellbeing approaches set out in the Commission’s final report are a good start, implicit and explicit assumptions within the public management system create challenges for implementing a comprehensive wellbeing approach.

These challenges have been discussed in a variety of studies that have examined Aotearoa New Zealand’s policymaking approach and system settings.1

There is often a narrow focus on economic growth and material prosperity

This narrow focus sometimes stems from a view that even non-material aspects of wellbeing, such as health and life satisfaction, flow from increased individual and national prosperity, often measured using Gross Domestic Product (GDP). While the Living Standards Framework and He Ara Waiora are intended to address this issue, more could be done to truly operationalise these frameworks into policy and investment advice and decision making.

Some values are emphasised over others

The system (implicitly) prioritises “western” ways of doing things over indigenous and/or more diverse views of wellbeing. This has resulted in the prioritisation of the individual as the focus of policy action (individualism), rather than prioritising collectives, such as family, whānau and communities (collectivism). In contrast, He Ara Waiora, and the All-of-Government Pacific Wellbeing Strategy emphasise a more collective and intergenerational perspective on economic and community activity. However, there remains a tendency for wellbeing policy and investment analysis to default to the types of values set out in the Living Standards Framework alone.

The system struggles to recognise or account for the full range of impacts on wellbeing when making decisions

The still largely siloed nature of the current public management system means that decisions in one part of government may undermine efforts in another part to improve wellbeing. The current system settings need to change to enable the system to focus on complementarities, by encouraging policymakers to uncover and respond to the complex linkages between the decisions being made by different government agencies motivated by different wellbeing objectives.

The current system is overly focused on short-term outcomes and struggles to consider the future

This is reflected in the Budget process, which focuses on the next four years of funding, and in agency statements of intent and reporting cycles, which are often shorter. Investment decisions give disproportionately greater weight to short-term benefits and costs, relative to the needs of future generations. System settings need to change so that policymakers give greater weight in planning and investment decisions to long-term challenges and the needs and rights of future generations.

The system often fails to respond to people experiencing multiple challenges at the same time

People experiencing persistent disadvantage often face multiple challenges at the same time. Yet the system attempts to achieve wellbeing outcomes for them through the accumulated efforts of individual agencies – each focusing on doing their job well but working in isolation. As noted by the OECD, “public policy makers have traditionally dealt with social problems through discrete interventions layered on top of one another. However, such interventions may shift consequences from one part of the system to another or continually address symptoms while ignoring causes.” Shifting system settings to support a connected, multi-sector approach would enable the public sector to make more effective progress towards improving the wellbeing of people experiencing persistent disadvantage.

The system does not pay enough attention to the distribution of wellbeing across individuals, families, whānau and communities

To address persistent disadvantage, more emphasis needs to be given to the distributional impacts of policies and programmes, so individuals, families, whānau and communities most in need get the attention and resources they require. Shifting system settings to consider distributional impacts (which may result from a range of factors, including power imbalances and access to opportunities and resources) would help to improve wellbeing for a greater number of individuals, families, whānau and communities – particularly for those experiencing persistent disadvantage.

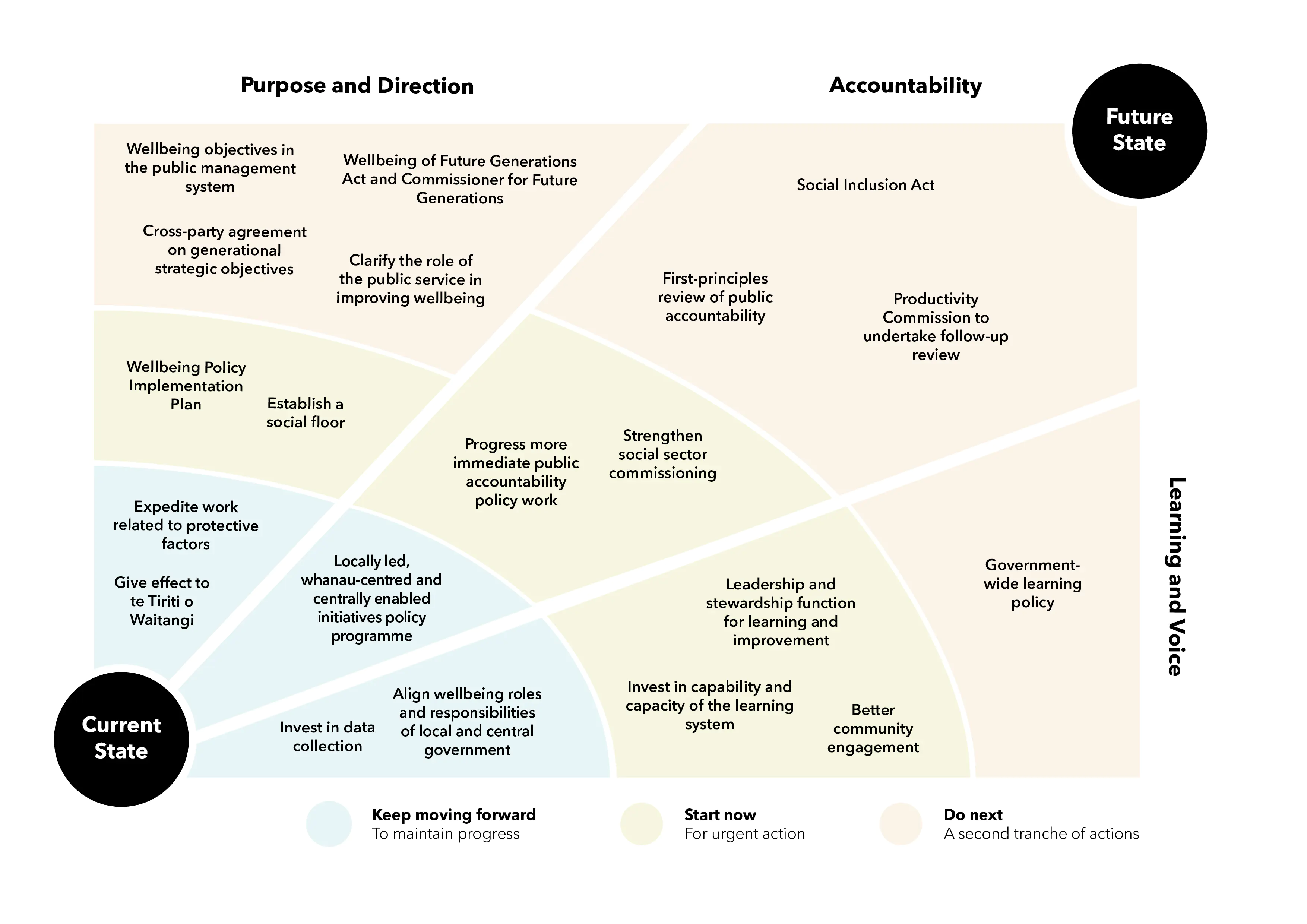

A clearer system purpose and direction for wellbeing is needed

Aotearoa New Zealand was an early adopter of wellbeing measurement frameworks and the introduction of a Wellbeing Budget, and we commend this growing emphasis on wellbeing. However, the current wellbeing approach leans heavily on measurement and lacks true integration into the public management system. Aotearoa New Zealand has been at the forefront of international wellbeing approaches, but other countries are now operationalising wellbeing better.

Public accountability settings need to be re-focused...

Current accountability settings constrain more innovative and effective ways of addressing persistent disadvantage. We have identified three critical gaps in the accountability system:

- weak direct accountabilities for ministers and the public service in addressing persistent disadvantage and the needs of future generations;

- the neglect of te Tiriti o Waitangi (te Tiriti) as a foundational constitutional document; and

- settings that constrain ongoing learning and more innovative and effective ways of addressing persistent disadvantage, including relational, collective and trust-based approaches.

These gaps reflect an overemphasis on preventing abuse of power, and focusing on “delivery” rather than results, leading to a “pseudo-accountability” trap. They also reveal settings that are out of sync with the intent of other public sector reforms to the Public Service Act 2020 and Public Finance Act 1989, particularly those around the provision of more modern, connected, citizen-focused public services. This is limiting the effective operation of those reforms.

...to support locally led, whānau-centred and centrally enabled approaches

Locally led, whānau-centred and centrally enabled approaches can provide more effective and responsive assistance to individuals, families, and whānau experiencing persistent disadvantage. However, Aotearoa New Zealand’s public accountability and funding settings do not yet adequately enable and support more trust-based and devolved ways of providing public services, or the relational commissioning approaches committed to in the Social Sector Commissioning Action Plan. Moreover, the approaches that do exist are typically under-resourced and struggle to meet the level of need and aspirations within communities.

To resolve this, policy work is needed to redesign accountability settings so the pursuit of ensuring appropriate use of public funds do not excessively constrain the cross-cutting nature of locally led, whānau-centred approaches. Likewise, contracting, monitoring, evaluation and learning approaches need to be more proportionate to the quantum of funding and risk involved.

The inquiry acknowledges the range of existing whānau-centred approaches to improving wellbeing and devolving direction setting and decision making to local communities. However, efforts across government are piecemeal, not fully coordinated and lack long-term funding arrangements,

which limits their potential effectiveness. Central government needs to take a stronger role to build enduring support (including funding pathways) for these initiatives. A whole-of-government approach to policy work in this space is needed, and roles and responsibilities need to be clearer.

Building a learning system

The inquiry found a need for a step-change in how the Aotearoa New Zealand public sector uses evidence and learns. To break the cycle of persistent disadvantage, the public management system needs to become a ‘learning system’, by:

- generating, synthesising and sharing what it is learning across the system (with policies and accountability mechanisms in place to ensure this happens and that what is being learned is acted on);

- including diverse views and perspectives to bring decision making closer to those experiencing persistent disadvantage, by engaging with people who are affected by government decisions, so they have input into shaping those decisions, as well as judging the impacts;

- supporting policymakers to take action now and in the future, to improve the lives of people experiencing persistent disadvantage; and

- taking an intergenerational lens, which includes ensuring the system-wide impacts of decisions over time are evaluated.