Overview: Tino Rangataritanga and Mana Motuhake

Prior to delving into the individual themes, the concepts of Tino Rangatiratanga and Mana Motuhake will be explored, and upfront definitions and overviews of these concepts will be provided within the context of this inquiry – their links to Te Tiriti o Waitangi will also be highlighted where appropriate.

Tino Rangatiratanga and Mana Motuhake – A form of positive and negative freedom

As Tino Rangatiratanga and Mana Motuhake both have overlapping ideas and concepts, confusion often arises between the two. To illustrate these two concepts in a simple way, their differences will be illustrated through the lens of negative and positive freedom. Put simply, negative freedom looks at the absence of obstacles, barriers, and constraints to living the way you want to live – for example, being able to exercise your customary fishing rights without barriers. On the other hand, positive freedom looks at the presence of control, self-mastery, and/or self-determination which ultimately enables you to take advantage of your negative freedom – for example, having the means to take advantage of your customary fishing rights (e.g., learning how to fish, having the right equipment). The concept of Tino Rangatiratanga can be seen as a form of negative freedom, while Mana Motuhake can be seen as a form of positive freedom.

In the context of this inquiry, many of those who continue to operate within the cycle of persistent disadvantage are often living in the absence of either one or both of these concepts, and many of the responses during the deep-dive wānanga related to a lack of either negative or positive freedom (Tino Rangatiratanga and Mana Motuhake).

Tino Rangatiratanga – A form of ‘negative freedom’

While a solid definition of Tino Rangatiratanga remains uncertain, the concept is often translated to mean a form of sovereignty, and while there are parallels between the two, Tino Rangatiratanga can be viewed as much more than merely ‘sovereignty’. In the context of this inquiry, Tino Rangatiratanga points to the ability for both the individual and the collective to choose their own way of life, free from the barriers, obstacles, and constraints often placed on those within the cycle of disadvantage.

While often viewed as a concept, Tino Rangatiratanga is also a form of practice. It is about living in accordance with tikanga (customs), while providing choice and opportunity for generations to come. It is about ensuring that both the natural environment and the property that has been guaranteed under Te Tiriti o Waitangi is maintained – free of any constraints – and is available for the benefit of our tamariki (children), and our mokopuna (grandchildren) in the future.

Mana Motuhake – A form of ‘positive freedom’

Mana Motuhake is often translated to mean many different things; Māori autonomy, independence, self-government, and self-determination to name a few. Sir Mason Durie describes Mana Motuhake and self-determination as being, “… about the advancement of Māori people, as Māori, and the protection of the environment for future generations”. When looking at the first part of Durie’s definition – ‘the advancement of Māori people, as Māori…’ – we understand that Mana Motuhake is not just about the higher-level political and societal decision-making, but rather, it looks at being able to advance yourself and your people in a practical sense. It is about having the control, the self- mastery, and the self-determination to advance yourself as an individual and as a people by taking advantage of the rights and responsibilities afforded to you – much in line with the idea of ‘positive freedom’. From a practical point-of-view, this might mean using your land and your resources for the betterment of your people. It might also mean being able to uphold and continue the tradition of customary practice (e.g., fishing, hunting, and cultivation) which has long seen Māori supplement a lifestyle that isn’t reliant on a capitalist construct.

Key Theme 1: Disconnection from one's culture/lack of identity

“We don’t get deep enough into the heart of the issue,

that’s why it becomes a ‘persistent’ cycle.”

Inquiry questions – Disconnection from one’s culture/lack of identity

- Why do Māori sometimes feel disconnected from their culture?

- What causes this disconnection?

- How does this disconnection leave Māori in a place of vulnerability and disadvantage?

- How does being connected to one’s culture drive greater long-term productivity?

A key theme that was identified throughout the deep-dive wānanga regarded a disconnection from one’s culture being a root-cause of the symptoms that continue to drive the cycle of persistent disadvantage. Further to this, participants pointed to a possible link between colonisation, the resulting deracination of Māori, and the persistent cycle of disadvantage.

Verbatim response: “People are disconnected culturally, socially, and linguistically from a base, this is what leads to all the symptomatic issues that are seen in society, such as mental health issues, and alcohol and drug addiction… underneath these symptoms are a driving cause, which is that people feel disconnected, they don’t have a sense of identity.”

Participants felt that being connected with one’s culture facilitated a sense of worth, tradition, confidence, and intergenerational knowledge transmission within individuals. Participants generally agreed that Māori who felt a sense of connection with their culture, were more likely to feel a sense of expectation on them to succeed and create something for themselves and for their mokopuna. Those who didn’t feel this sense of expectation and self-worth often get left behind in the cycle, or even worse, end up on the wrong side of the law and before the courts.

Verbatim response: “...kāore ratou i te mōhio ko wai rātou, nō hea rātou, ko wai ō rātou iwi... I have seen multiple generations of Māori defendants before the courts who do not know who they are, where they come from, and which iwi they belong to. There has long been this intergenerational loss of identity in the courts and it is a huge challenge for them to find their way back.”

Sub-theme: Is the disconnection from one’s culture a ‘root-cause’ of the disadvantage cycle?

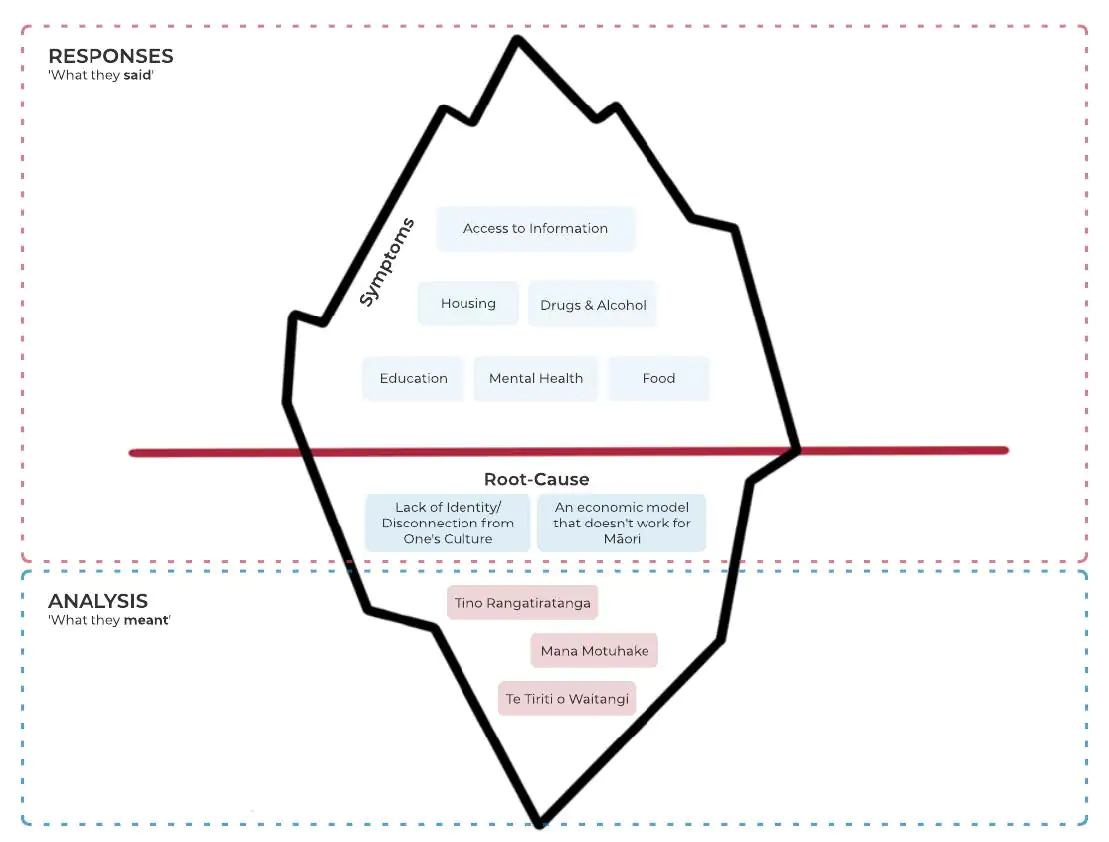

The initial deep-dive wānanga set down the foundation for a dialogue of conversation pertaining to one’s disconnection from their culture being a ‘root-cause’ of many of the symptomatic issues that are often highlighted as outcomes of the disadvantage cycle. Symptoms are the external issues regularly seen within the community (e.g., housing, education). The root-causes are the underlying factors that contribute and drive the emergence of symptoms (e.g., a disconnection from one’s culture, an economic model that doesn’t work for Māori). There was general agreement between participants that the inquiry should focus on root-cause issues rather than symptomatic issues. It was also common concensus that the Governments of the last few decades had not done enough to address the root-cause, but rather, continually looked to address the symptoms.

Verbatim response: “I think that some of the solutions that we come up with are like band- aids, they just try and deal with one little thing, I think it’s a lot more complex than that. We see symptoms of the issue and we try and fix the symptom, like a drug and alcohol program that gets implemented after the drug and alcohol becomes a problem. You really have to think about what has led to that, where has that symptom come from.”

Key Theme 2: The need for an 'Aotearoa economy'

“We need an ‘Aotearoa economy’, one that puts people at the center”.

Inquiry questions – the need for an ‘Aotearoa economy’

- What does an ‘Aotearoa economy’ look like?

- How would an ‘Aotearoa economic model’ differ from the current economic model?

- What does productivity for Māori look like?

Verbatim response: “I see the true measure of productivity and the success of te ōhanga Māori (the Māori economy) being our ability to drive transformative change in our people’s lives… when we are considering how to reshape our economic activity and what an ‘Aotearoa economy’ looks like, I think it’s one that puts people at the center”.

This theme was discussed primarily by business leaders that we spoke with who viewed persistent disadvantage from an economic perspective. The possible inquiry questions outlined above were touched on during the deep-dive wānanga, however, require further examination to understand the economic drivers behind the cycle of persistent disadvantage. The discussion below should be viewed as a possible beginning to a wider discussion which requires input from all factions of society – particularly within the Māori community. Discussions with participants regarding this theme are outlined below and are supported with the relevant evidence that was provided during these discussions.

The grounding for an ‘Aotearoa economy’

For several decades now we have enjoyed an economy that works on free market principles; based on supply and demand and the production of goods and services. While there are many benefits to this form of economy, there are certain members of society whose skills are not marketable, and this results in them having a higher chance of falling into unemployment. Over time, this effect compounds and they (along with their families) fall into a cycle of persistent economic poverty – otherwise known as a ‘persistent cycle of disadvantage’. As discussed in our wānanga, unfortunately for Māori, this situation is all too real.

Several of the statistics highlighted in the wānanga related to the disadvantage that Māori are presented with – which all reinforce the theory outlined above. These included poorer health outcomes, poorer educational outcomes, and an overall poorer economic standing. Conversely, if we look at some of the statistics regarding the importance of certain economic factors to Māori, nearly 92% of the Māori population see the health of the natural environment as something that is ‘very important’, 71% also view being engaged in Māori culture as important.1 In order for Māori priorities to form a cornerstone of a new economic model, it is these types of factors which will provide Māori with a greater sense of Tino Rangatiratanga and Mana. This is an economic model that puts people and their values at the heart of it.

Considering social impact – ‘asset allocation vs. impact allocation’

Verbatim response: “I like to have some rules when looking at investments and improving our wellbeing, one is that you need a financial return… we’re not ‘for profit’, but we’re also not ‘for loss’. You also need to have a social return, essentially thinking about how we are advancing the interests of the iwi”.

The concept of putting people at the center of a new economic model probed further discussion into both the benefits and the costs of this type of model. To Māori, the importance of social impact is not to be understated as economic-based decisions are often considered in the context of a wider ‘social ROI’ – something that was discussed heavily during one of the deep-dive wānanga. The participants of this wānanga spoke of their ambition to advance their respective iwi and hapū, both from an economic and social perspective. They spoke of being often confronted with the dilemma of ‘asset allocation vs. impact allocation’, and the importance of achieving both an economic return-on- investment (ROI) while providing a social ROI to their respective iwi and hapū – something that would form a cornerstone of a successful ‘Aotearoa economy’. Below is a thought presented by a participant regarding the true purpose of money and its responsibility to sustain people.

“E rua, e rua te kūmara me te pūtea, kāore he hua ōna ki tua atu o te whāngai i te tangata”.

Money is like a kumara, it has no value outside of its ability to sustain people”.

An economic model based on ‘tauutuutu’ – the principle of reciprocity

Verbatim response: “I went fishing in Japan and caught a beautiful shimaji [fish], and I asked the interpreter to throw it back for me. They didn’t understand that, and they asked, ‘Why would you do that?’, so I replied, ‘the first fish is for Tangaroa’. The fact of the matter is, the Māori world is built on a reciprocal economy, not an extractive economy, and our success in that economy is not just based on the value that we accrue, but the value that we contribute back to it”.

The concept of tauutuutu (reciprocity) forms a key part of the relationship that Māori have with the environment and participants stated that they would consider this concept critical to an ‘Aotearoa economy’ that provides for everybody. How we interact with our environment impacts its sustainability and therefore its ability to lift people out of the cycle of persistent disadvantage.

Key Theme 3: An education system that isn't fit for purpose

Inquiry questions – An education system that isn’t fit for purpose

- What does an education system that works for Māori look like?

- How could educational opportunities and outcomes for Māori be improved?

- What are the impacts of greater educational opportunities and outcomes on the persistent cycle of disadvantage?

While this could be considered a symptomatic issue of some of the root-cause issues outlined in the key themes above, access to education opportunities and raising educational outcomes for Māori who continue to be bound by the ties of persistent disadvantage continued to be important to almost all participants. Due to the wide nature of sub-themes and lived experiences shared, their verbatim examples and feedback have been provided below.

On the educational opportunities often afforded to Pākehā, but not afforded to Māori: “I had a friend [assumed to be non-Māori] who sent her kids to a private school and to Kip McGrath. Despite this, they continued to struggle and went on to become average students. Yet, I know there are so many of our own Māori students who don’t have the opportunity to go to a private school or to engage in extra-curricular learning who are very intelligent, however, they drop out because they don’t have that whole push and expectation behind them to succeed”.

On the educational life cycle of Māori: “There is a difference in the educational cycle that Māori go through, traditionally, non-Māori were taught to go to school and get a qualification, and then have a career, and then have a family. Māori have a very different educational cycle… we go to school and often struggle in a mainstream schooling system, this leads to a lack of motivation, and we eventually drop out, we have a family early and as a result, our employment is often sporadic. We often become second chance learners later in life…”.

Not poor enough to apply for benefits, not wealthy enough to provide opportunity: “As a principal, I had to plead a case on behalf of a Year 8 student to go to boarding school... the family was not poor enough to get any benefit, they didn’t have the same access to support that poorer families have, but they couldn’t afford to send the student to boarding school”.

On the inherent deficit-thinking within the mainstream curriculum: “The Ministry of Education continues to put out this material [Māori as a poster-person of ‘second-chance learners’] that reinforces the deficit-thinking inherent within the mainstream curriculum around Māori education and learning… this reinforces the inherent bias within the current system. The question is, ‘how do we move away from this ‘poverty of the mind’ view?”.

On tall-poppy syndrome: “Whānau who have had poor education themselves often cut their children down when they are doing well. I was taking some kids down to our local squash club here in Te Puke where we run a disadvantaged children’s program. I was picking the kid up when the father just said to his kid, “you know it’s all rubbish aye”, you don’t need to be doing that… and immediately the boy pulled out. I just thought it was a great opportunity for him to get out after school and get away from all the drinking and what not that goes on at home”.

On access to information and the path to financial assistance: “Knowing where to find things is often hard... for example, we have been trying to apply to get into university, or to get a higher education which we have to pay for. We went looking around for grants and all that but didn’t really know where to go. When you figure out where to go, you have to figure out how to do it... and then after getting to university we found that there were many of us in the same boat. Support around those things would have been huge”.

Key Theme 4: Intergenerational/communal living

Inquiry questions – Intergenerational/communal living

- How could intergenerational/communal living bring Māori out of the cycle of persistent disadvantage?

- What opportunities could be provided to Māori for them to live in an intergenerational and communal manner?

The final key theme observed across the deep-dive wānanga regarded the ability to lift people out of the cycle of persistent disadvantage through intergenerational/communal living. Māori have long been communal living people who thrived and survived in communal living spaces. Many Māori, particularly in rural areas of Aotearoa, continue to live in this way and choose not to conform to the ideals of mainstream society. Rather, we choose to ‘live off the land’ through hunting, fishing, growing, and gathering our own kai (food). Many see this as an act of exercising their Tino Rangatiratanga and Mana Motuhake.

“Before colonisation and during the early period of Pākehā settlement, we lived in kāinga: clusters of dwellings occupied by whānau or hapū and associated with shared resources. Often there was a fortified pā [village] that could be retreated to in times of conflict. There were also seasonal encampments associated with mahinga kai – food gathering areas. To maintain access to resources, we needed to negotiate and maintain good relationships with our neighbouring whānau and hapū.”2

While acknowledging the belief that some participants have around this form of living being a customary right, there are also many other benefits to this type of living that participants believed would contribute to breaking the cycle of disadvantage.

Rebuilding the sense of whakapapa and connection

Connection to whānau, hapū and iwi, as well as tūrangawaewae [place of belonging] is crucial to building a sense of identity and culture within te ao Māori. Those who were raised around their whānau while being embraced in their culture felt a strong sense of connection with their whakapapa and felt supported to succeed. For those who were trying to reconnect with their whānau and tūrangawaewae, communal living situations such as papakāinga provided that space for reconnection, learning, and intergenerational knowledge transmission.

Verbatim response: “It’s hard to find your way back [to your tūrangawaewae] when it’s been 3 or 4 generations since your ancestors lost touch with where they were from”.

The legislative barriers to entry

Despite the many advantages to papakāinga living, participants were frustrated at the bureaucracy and confusion regarding the establishment of papakāinga. The large amount of ‘red-tape’ associated with establishing this form of living often drove whānau Māori away from this process and forced them into living situations which they didn’t desire. The list of current land and housing policies regarding the establishment of papakāinga that participants spoke of included:

- Resource Management Act 1991

- Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993

- Local Government Act 2002

- Other bespoke Treaty of Waitangi settlement legislations.

These legislative boundaries were viewed as needing to be reviewed and redesigned to allow and encourage the intergenerational/communal style of living.

Verbatim response: “We need to stop living in this whole nucleus kind of arrangement [mum, dad, and kids], that model has never worked for our people. How do we live cost effectively, have living and housing arrangements that suit multiple generations of living together, and is financially sustainable? It works where the income that we generate all goes into the bigger pot and we all live well rather than you living poor over there by yourself and me living poor over here by myself”.