Advisory Group on Conduct Problems. (2009). Conduct problems: Best practice report [Report]. MSD. www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/conduct- problems-best-practice/conduct-problems.pdf

Aguiar, W., & Halseth, R. (2015). Aboriginal peoples and historic trauma: The processes of intergenerational transmission. National Collborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/context/ RPT-HistoricTrauma-IntergenTransmission-Aguiar-Halseth-EN.pdf

Andersen, L. S., Gaffney, O., Lamb, W., Hoff, H., & Wood, A. (2020). A safe operating space for New Zealand/ Aotearoa: Translating the planetary boundaries framework. Ministry for the Environment. www.environment.govt.nz/publications/a-safe-operating-space-for-new-zealandaotearoa-translating- the-planetary-boundaries-framework/

Ardern, J. (2018). Child Poverty Reduction Bill—A background summary. The Beehive. www.beehive.govt.nz/ sites/default/files/2018-01/Child%20Poverty%20Reduction%20Bill%20backgrounder_0.pdf

Atkinson, J., Salmond, C., & Crampton, P. (2019). NZDep2018 Index of Deprivation [Final Research Report, December 2020]. University of Otago. www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/otago823833.pdf

Babian, L., Beatty, J., Bennetts, K., Loh, E., McKibben, D., & Russell, J. (2021). Kia whaihua mō te oranga: Placing value on wellbeing – Alternative approaches to assessing and prioritising public initiatives. ANZSOG. www.mbie.govt.nz/dmsdocument/25087-placing-value-on-wellbeing-anzsog-report-pdf

Baker, M. G., Telfar Barnard, L., Kvalsvig, A., Verrall, A., Zhang, J., Keall, M., Willson, N., Wall, T., & Howden- Chapman, P. (2012). Increasing incidence of serious infectious diseases and inequalities in New Zealand: A national epidemiological study. The Lancet, 379, 1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140- 6736(11)61780-7

BarBrook-Johnson, P., Sharpe, S., Pasqualino, R., Moura, F. S. D., Nijsee, F., Vercoulen, P., Clark, A., Peñasco, C., Anadon, L. D., Mercure, J.-F., Hepburn, C., Farmer, J. D., & Lenton, T. M. (2023). New economic models of energy innovation and transition: Addressing new questions and providing better answers. The Economics of Energy Innovation and System Transition (EEIST). https://eeist.co.uk/eeist-reports/ new-economic-models-of-energy-innovation-and-transition/

Berentson-Shaw, J. (2018). Telling a new story about ‘child poverty’ in New Zealand [A report prepared by The Workshop for The Policy Observatory, Auckland University of Technology]. The Workshop, The Policy Observatory. www.theworkshop.org.nz/publications/telling-a-new-story-about-child-poverty-in- new-zealand-2018

Bishop, R., & Berryman, M. (2006). Culture speaks: Cultural relationships and classroom learning. Huia Publishers.

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Tiakiwai, S., & Richardson, C. (2003). Te Kotahitanga Phase 1: The experiences of Year 9 and 10 Māori students in mainstream classrooms [Report to the Ministry of Education]. Ministry of Education. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi= a9cf5dc1a44d4b6d63182a5b1c2773ac21558a58

Boston, J. (2021a). Assessing the options for combatting democratic myopia and safeguarding long-term interests. Futures : The Journal of Policy, Planning and Futures Studies, 125, 102668-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2020.102668

Boston, J. (2021b). Protecting long-term interests: The role of institutions as commitment devices. In Giving future generations a voice (pp. 86–107). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Boston, J., Bagnall, D., & Barry, A. (2019). Foresight, insight and oversight: Enhancing long-term governance through better parliamentary scrutiny. Institute of Governance and Policy Studies, Victoria Univeristy of Wellington. www.victoria.ac.nz/ data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1753571/Foresight-insight-and-oversight.pdf

Boston, J., Bagnall, D., & Barry, A. (2020). Enhancing long-term governance: Parliament’s vital oversight role. Policy Quarterly, 16(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v16i1.6354

Brandsen, T., Steen, T., & Verschuere, B. (2018). Co-creation and co-production in public services: Urgent issues in practice and research. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315204956-1

Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports, 129(Suppl 2), 19–31.

Bray, R., Gray, M., & Hart, P. ’t. (2019). Evaluation and learning from failure and success. Australia & New Zealand School of Government. www.anzsog.edu.au/research-insights-and-resources/research/ learning-from-failure-and-success/

Bush, N. R., Noroña-Zhou, A., Coccia, M., Rudd, K. L., Ahmad, S. I., Loftus, C. T., Swan, S. H., Nguyen, R. H. N., Barrett, E. S., Tylavsky, F. A., Mason, W. A., Karr, C. J., Sathyanarayana, S., & LeWinn, K. Z. (2023). Intergenerational transmission of stress: Multi-domain stressors from maternal childhood and pregnancy predict children’s mental health in a racially and socioeconomically diverse, multi-site cohort. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02401-z

Carey, G., & Crammond, B. (2015). What works in joined-up government? An evidence synthesis. International Journal of Public Administration, 38(13–14), 1020–1029. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2014.982292

Carlisle, K., & Gruby, R. L. (2019). Polycentric systems of governance: A theoretical model for the commons. Policy Studies Journal, 47(4), 927–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12212

Caulkin, S., Pell, C., O’Donovan, B., & Mack, J. (Eds.). (n.d.). The Vanguard Periodical. The Vanguard Method in people centred services (Edition Two). Vanguard Consulting Ltd. https://dokumen.tips/documents/ the-vanguard-periodical-vanguard-periodical-the-vanguard-method-in-people-centred.html?page=1

Center on the Developing Child. (2010). The foundations of lifelong health are built in early childhood. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Foundations-of-Lifelong-Health.pdf

Chapman, J., & Duncan, G. (2007). Is there now a new ‘New Zealand model’? Public Management Review, 9, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030600853444

Clerk of the House of Representatives. (2022). Submission on the review of Standing Orders 2023. Parliamentary scrutiny of the Executive [Submission]. Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives. www.parliament. nz/resource/en-NZ/53SCSO_EVI_122709_SO116/91ba0b16edb32a779395effdd73377a9293b4137

Cochrane, B., & Pacheco, G. (2022). Empirical analysis of Pacific, Māori and ethnic pay gaps in New Zealand [Research Note]. New Zealand Work Research Institute. https://workresearch.aut.ac.nz/ data/assets/ pdf_file/0004/672205/7e71e4dbee2432b576ef6fbc348f4d7109cdd073.pdf

ComVoices. (2022). Insights from social policy research on communities and Covid-19. https://comvoices.org. nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/COMVOICES-Community-Research-Seminar-Report.pdf

Connolly, J. (2023). Causal diagrams to support ‘A fair chance for all’. www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/ Inquiries/a-fair-chance-for-all/A-Fair-Chance-for-All-Causal-Diagrams-2023.05.03.pdf

Controller and Auditor-General. (2019). Public accountability: A matter of trust and confidence (A Discussion Paper Presented to the House of Representatives under Section 20 of the Public Audit Act 2001 B.29[19e]). https://oag.parliament.nz/2019/public-accountability/docs/public-accountability.pdf

Controller and Auditor-General. (2021a). Building a stronger public accountability system for New Zealanders (Presented to the House of Representatives under Section 20 of the Public Audit Act 2001 B.29[21h]). https://oag.parliament.nz/2021/public-accountability/docs/public-accountability.pdf

Controller and Auditor-General. (2021b). Summary—Working in new ways to address family violence and sexual violence. https://oag.parliament.nz/2021/joint-venture/docs/summary-joint-venture.pdf

Controller and Auditor-General. (2021c). The Government’s preparedness to implement the sustainable development goals (Presented to the House of Representatives under Section 20 of the Public Audit Act 2001 B.29[21g]). https://oag.parliament.nz/2021/sdgs/docs/sustainable-dev-goals.pdf

Controller and Auditor-General. (2021d). The Government’s preparedness to implement the sustainable development goals (Presented to the House of Representatives B.29[21g]). www.oag.parliament. nz/2021/sdgs/docs/sustainable-dev-goals.pdf

Controller and Auditor-General. (2021e). The problems, progress, and potential of performance reporting (Presented to the House of Representatives under Section 20 of the Public Audit Act 2001 B.29[21j]). https://oag.parliament.nz/2021/performance-reporting/docs/performance-reporting.pdf

Controller and Auditor-General. (2023). How well public organisations are supporting Whānau Ora and whānau-centred approaches (B.29[23a]). Office of the Auditor-General. https://oag.parliament.nz/2023/ whanau-ora

Cookson, R., Doran, T., Asaria, M., Gupta, I., & Mujica, F. P. (2021). The inverse care law re-examined: A global perspective. Lancet, 397(10276), 828–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00243-9

Cottam, H. (2020). Welfare 5.0: Why we need a social revolution and how to make it happen (Policy Report IIPP 2020-10). Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public- purpose/publications/2020/sep/welfare-50-why-we-need-social-revolution-and-how-make-it- happen#:~:text=make%20it%20happen-,Welfare%205.0%3A%20Why%20we%20need%20a%20 social%20revolution%20and%20how,of%20a%20new%20social%20settlement.

Dale, C. (2021, December 23). How to take the interests of future generations into account [Opinion]. NZ Herald. www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/claire-dale-how-to-take-the-interests-of-future-generations-into-account/3G2SRI5T5HWADAORCRS3DCXMVA/

Davidson, J. (2020). #FutureGen, lessons from a small country. Chelsea Green Publishing.

De Neve, J.-E., Clark, A. E., Krekel, C., Layard, R., & O’Donnell, G. (2020). Taking a wellbeing years approach to policy choice. BMJ, 2020(371), m3853. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3853

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2022). Review of the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy— Findings and recommendations. www.childyouthwellbeing.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2022-09/proactive- release-briefing-cyw-strategy-findings-recommendations.pdf

Dietz, T., Fitzgerald, A., & Shwom, R. (2005). Environmental values. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 30, 335–372. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144444

Dormer, R., & Ward, S. (2018). Accountability and public governance in New Zealand (Working Paper No. 117). School of Accounting and Commercial Law, Victoria University of Wellington. www.wgtn.ac.nz/ data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1869021/wp-117.pdf

DPMC. (2022). Review of the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy—Findings and recommendations (Briefing DPMC-2021/22-2587). www.childyouthwellbeing.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2022-09/proactive-release- briefing-cyw-strategy-findings-recommendations.pdf

Durie, M. (2017). Indigenous suicide: The Turamarama Declaration. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing Te Mauri - Pimatisiwin, 2(2), 59–67.

Edwards, B. (2022, June 23). Wealthy can buy access to power – And politicians don’t want this changed. Democracy Project. https://democracyproject.nz/2022/06/23/bryce-edwards-wealthy-can-buy-access- to-power-and-politicians-dont-want-this-changed/

Engelbrecht, H.-J. (2013). The Living Standards Framework and Innovation.

Eppel, E., & O’Leary, R. (2021). Retrofitting collaboration into the new public management: Evidence from New Zealand (A. Whitford & R. Christensen, Eds.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108906357

Espiner, G. (2023a, March 23). How well-connected lobbyists ask for—And receive—Urgent meetings, sensitive information and action on law changes for their corporate clients [News]. RNZ. www.rnz.co.nz/ news/in-depth/486527/how-well-connected-lobbyists-ask-for-and-receive-urgent-meetings-sensitive- information-and-action-on-law-changes-for-their-corporate-clients

Espiner, G. (2023b, March 25). Lobbyists in New Zealand enjoy freedoms unlike most other nations in the developed world [News]. RNZ. www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/486670/lobbyists-in-new-zealand-enjoy- freedoms-unlike-most-other-nations-in-the-developed-world

Financial Times. (2020, April 4). Virus lays bare the frailty of the social contract [News]. www.ft.com/content/7eff769a-74dd-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795.

Frameworks Institute. (2020). Mindset shifts: What are they? Why do they matter? How do they happen? [A FrameWorks Strategic Report]. www.frameworksinstitute.org/publication/mindset-shifts-what-are- they-why-do-they-matter-how-do-they-happen/

FrankAdvice. (2023). A learning system for addressing persistent disadvantage. NZPC. www.productivity.govt. nz/assets/Documents/a-learning-system-for-addressing-persistent-disadvantage/A-learning-system-for- addressing-persistent-disadvantage-final.pdf

Fry, J. (2022). Together alone: A review of joined-up social services. NZPC. www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/ Documents/Together-alone_A-review-of-joined-up-social-services.pdf

Future Generations Commissioner for Wales. (2020). The future generations report. www.futuregenerations. wales/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/FGC-Report-English.pdf

Future Generations Commissioner for Wales. (2022). Future generations: Commissioner for Wales peformance report 2021-2022 [Summary]. www.futuregenerations.wales/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/ FG-Summary-2022.pdf

Gaukroger, C., Ampofo, A., Kitt, F., Phillips, T., & Smith, W. (2022). Redefining progress: Global lessons for an Australian approach to wellbeing. Centre for Policy Development. https://cpd.org.au/wp-content/ uploads/2022/08/CPD-Redefining-Progress-FINAL.pdf

Gilens, M., & Page, B. I. (2014). Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), 564–585. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714001595

Gill, D. (2000). New Zealand experience with public management reform—Or why the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence. International Public Management Journal, 3(2000), 55–66.

GOV.UK. (n.d.). What works network [Guidance]. Retrieved 24 May 2023, from www.gov.uk/guidance/what-works-network

Graham, H., & Bell, S. (2021). The representation of future generations in newspaper coverage of climate change: A study of the UK press. Children & Society, 35(4), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12411

Gunasekara, F., & Carter, K. (2012). Dynamics of income and deprivation in New Zealand, 2002-2009: A descriptive analysis of the survey of family, income and employment (SoFIE) (Public Health Monograph Series No. 24). Department of Public Health, University of Otago. www.occ.org.nz/documents/103/ Dynamics-of-Income.pdf

Haemata Limited. (2022a). Colonisation, racism and wellbeing. www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Documents/ NZPC_Colonisation_Racism_Wellbeing_Final.pdf

Haemata Limited. (2022b). Māori perspectives on public accountability [Final Report]. Office of the Auditor- General. https://oag.parliament.nz/2022/maori-perspectives/docs/maori-perspectives.pdf

Haemata Limited. (2022c). Wānanga feedback report [Prepared for New Zealand Productivity Commission].NZPC. https://www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Inquiries/a-fair-chance-for-all/Haemata-Wananga- Feedback-Report-A-Fair-Chance-for-All.pdf

Hagen, P., Tangaere, A., Beaton, S., Hadrup, A., Taniwha-Paoo, R., & Te Whiu, D. (2021a). Designing for equity and intergenerational wellbeing: Te Tokotoru [Innovation Brief]. The Auckland Co-Design Lab, The Southern Initiative, Auckland Council. https://static1.squarespace.com/ static/5f1e3bad68df2a40e2e0baaa/t/619d6ee9ce2a4c268892b683/1637707507280/TeTokotoru_Oct_ InnovationBrief_2021.pdf

Hagen, P., Tangaere, A., Beaton, S., Hadrup, A., Taniwha-Paoo, R., & Te Whiu, D. (2021b). Designing for equity and intergenerational wellbeing: Te Tokotoru. The Southern Initiative. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f1e3bad68df2a40e2e0baaa/t/619d6ee9ce2a4c268892b683/1637707507280/ TeTokotoru_Oct_InnovationBrief_2021.pdf

Health and Disability System Review. (2020). Health and disability system review [Final report - Pūrongo Whakamutunga]. www.systemreview.health.govt.nz/final-report

Holzer, H., Whitmore Schanzenbach, D., Duncan, G., & Ludwig, J. (2008). The economic costs of childhood poverty in the United States. Journal of Children & Poverty, 14(1), 41–61. https://doi. org/10.1080/10796120701871280

HQSCNZ. (2019). A window on the quality of Aotearoa New Zealand’s health care 2019 – A view on Māori health equity. Health Quality & Safety Commission NZ. www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/Our-data/Publications- resources/Window_2019_web_final-v2.pdf

Hughes, P. (2019). Public service legislation and public service reform. Policy Quarterly, 15(4), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v15i4.5918

Hughes, T. (2022a). Social investment (in wellbeing?). Policy Quarterly, 18(3), 3–8.

Hughes, T. (2022b). The distribution of advantage in Aotearoa New Zealand: Exploring the evidence [Background Paper to Te Tai Waiora: Wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand 2022]. The Treasury. www. treasury.govt.nz/publications/tp/distribution-advantage-aotearoa-new-zealand-exploring-evidence

Human Learning Systems. (2021). Plymouth alliance for complex deeds. www.humanlearning.systems/ uploads/Plymouth%20Alliance.pdf

Human Rights Commission. (2022, July 18). New research reveals majority of the Pacific Pay Gap can’t be explained. www.scoop.co.nz/stories/BU2207/S00274/new-research-reveals-majority-of-the-pacific-pay- gap-cant-be-explained.htm

International Labour Office. (2012). The strategy of the International Labour Organization. Social security for all: Building social protection floors and comprehensive social security systems. International Labour Organization. www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---soc_sec/documents/publication/ wcms_secsoc_34188.pdf

Jones, N., O’Brien, M., & Ryan, T. (2018). Representation of future generations in United Kingdom policy- making. Futures : The Journal of Policy, Planning and Futures Studies, 102, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.01.007

Karacaoglu, G. (2021). Love you: Public policy for intergenerational wellbeing. Tuwhiri.

Kiro, C., Asher, I., O’Reilly, P., McGlinchey, T., Waldegrave, C., Brereton, K., Reid, R., McIntosh, T., Nana, G., Hickey, H., & Tautai, L. T. (2019). Whakamana tāngata: Restoring dignity to social security in New Zealand. Kia Piki Ake Welfare Expert Advisory Group. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/ DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE40597708

Knowles, M., Rabinowich, J., Ettinger de Cuiba, S., Becker Cutts, D., & Chilton, M. (2016). ‘“Do you wanna breathe or eat?”’: Parent perspectives on child health consequences of food insecurity, trade-offs, and toxic stress. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(1), 25–32.

Lahey, R. (2010). The Canadian M&E System: Lessons learned from 30 years of development (ECD Working Paper No. 23). World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/27909

Lahey, R., & Nielsen, S. B. (2013). Rethinking the relationship among monitoring, evaluation, and results- based management: Observations from Canada. New Directions for Evaluation, 2013(137), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.20045

Learning from the Waitangi Tribunal Māori health report. (2019). The Policy Place. https://thepolicyplace. co.nz/2019/07/the-ps-are-out/

Litmus Partner. (2021). Success frameworks for Place-Based Initiatives: Design and toolkit [Final report prepared for: Social Wellbeing Agency Toi Hau Tāngata]. Social Wellbeing Agency. https://swa.govt.nz/ publications/guidance/

Llena-Norzal, A., Martin, N., & Murtin, F. (2019). The economy of well-being: Creating opportunities for people’s well-being and economic growth (SDD Working Paper No. 102). https://one.oecd.org/ document/SDD/DOC(2019)2/En/pdf

Lodge, M., & Gill, D. (2011). Toward a new era of administrative reform? The myth of post-NPM in New Zealand. Governance, 24(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2010.01508.x

Lovelock, K. (2020). Implementation evaluation of Mana Whaikaha system transformation [Revised draft, Final version]. Allen+Clarke. https://manawhaikaha.co.nz/assets/Uploads/Mana-Whaikaha-Implementation- Evaluation-Final-Version-3-March-2020-002.pdf

Lowe, T. (2021). Managing and governing learning cycles. In Human learning systems: Public service for the real world (pp. 178–194). ThemPra Social Pedagogy. https://realworld.report/assets/documents/hls-real- world.pdf

Lowe, T., & Hesselgreaves, H. (2021). The HLS Principles: Learning. In Human learning systems: Public service for the real world (pp. 54–72). ThemPra Social Pedagogy. https://realworld.report/assets/documents/ hls-real-world.pdf

Lowe, T., & Plimmer, D. (2019). Exploring the new world: Practical insights for funding, commissioning and managing in complexity. Collaborate. https://collaboratecic.com/insights-and-resources/exploring-the- new-world-practical-insights-for-funding-commissioning-and-managing-in-complexity/

Lowe, T., & Wilson, R. (2017). Playing the game of outcomes-based performance management. Is gamesmanship inevitable? Evidence from theory and practice. Social Policy & Administration, 51(7), 981–1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12205

Manaaki Tairāwhiti. (2023). Manaaki Tairāwhiti. Manaaki Tairāwhiti. www.mt.org.nz/ Marmot, M. (2015). The health gap: The challenge of an unequal world. Bloomsbury Press.

Martin, B. H. (2016). Unsticking the status quo Strategic framing effects on managerial mindset, status quo bias and systematic resistance to change. Management Research Review, 40(2), 122–141. https://doi. org/10.1108/MRR-08-2015-0183

Mazey, S., & Richardson, J. (Eds.). (2021). Policy-making under pressure: Rethinking the policy process in Aotearoa New Zealand. Canterbury University Press. https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/engage/cup/recent/ policy-making-under-pressure-rethinking-the-policy-process-in-aotearoa-new-zealand.html

McAllister, T. (2022). Seen but unheard: Navigating turbulent waters as Māori and Pacific postgraduate students in STEM. Journal of The Royal Society of New Zealand, 52(sup1), S116–S134. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2022.2097710

McEwen, C. A., & McEwen, B. S. (2017). Social structure, adversity, toxic stress, and intergenerational poverty: An early childhood model. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 445–472. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev- soc-060116-053252

McLachlan, R., Gilfillan, G., & Gordon, J. (2013). Deep and persistent disadvantage in Australia [Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper]. Australian Productivity Commission. www.pc.gov.au/research/ supporting/deep-persistent-disadvantage

McMeeking, S., Kahi, H., & Kururangi, K. (2019). Implementing He Ara Waiora in alignment with the Living Standards Framework and Whanau Ora [Draft Recommendatory Report]. University of Canterbury. https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/17608/FNL%20TSY%20JULY%20HE%20ARA%20 WAIORA%20DESIGN%20REPORT.pdf?sequence=2

McMeeking, S., Kururangi, K., & Hamuera, K. (2019). He Ara Wairoa: Background paper on the development and content of He Ara Wairoa. University of Canterbury. https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/17576

McMullin, C. (2023). The persistent constraints of new public management on sustainable co-production between non-profit professionals and service users. Administrative Sciences, 13(37). https://doi. org/10.3390/admsci13020037

Menzies, M. (2022). Long-term insights briefings: A futures perspective. Policy Quarterly, 18(4), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v18i4.8017

Miller, R. J., Ruru, J., Behrendt, L., & Lindberg, T. (2010). Discovering indigenous lands: The doctrine of discovery in the English colonies. Oxford University Press.

Minister of Social Development and Employment. (2004). Reducing inequalities: Next steps [Cabinet paper]. www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/monitoring/reducing- inequalities/reducing-inequalities-next-steps.pdf

Ministry for Pacific Peoples. (2022). Pacific wellbeing strategy. Weaving all-of-government: Progressing Lalanga Fou. www.mpp.govt.nz/programmes/all-of-government-pacific-wellbeing-strategy/

Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment. (2022). Te Ara Paerangi: Future Pathways White Paper 2022. www.mbie.govt.nz/science-and-technology/science-and-innovation/agencies-policies-and-budget- initiatives/te-ara-paerangi-future-pathways/te-ara-paerangi-future-pathways-white-paper/white-paper/

Ministry of Health. (2021). Kia Manawanui Aotearoa: Long-term pathway to mental wellbeing. www.health.govt.nz/publication/kia-manawanui-aotearoa-long-term-pathway-mental-wellbeing

Ministry of Social Development. (2018). Rapid evidence review: The impact of poverty on life course outcomes for children, and the likely effect of increasing the adequacy of welfare benefits [Report for the Welfare Expert Advisory Group]. Ministry of Social Development. www.msd.govt.nz/documents/ about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/information-releases/weag-report-release/rapid- evidence-review-the-impact-of-poverty-on-life-course-outcomes-for-children-and-the-likely-effect-of- increasing-the-adequacy-of-welfare-benef.pdf

Ministry of Social Development. (2020). Place-Based Initiatives: Evaluation findings and long term funding [Cabinet Paper]. www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/information- releases/cabinet-papers/2020/place-based-initiatives-evaluation-findings-and-long-term-funding.html

Ministry of Social Development. (2022a). Social Sector Commissioning 2022-2028 Action Plan. www.msd.govt. nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/planning-strategy/social-sector-commissioning/ index.html

Ministry of Social Development. (2022b). Social sector commissioning: Sector update. www.msd.govt. nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/planning-strategy/social-sector-commissioning/social-sector-commissioning-update-2022.pdf

Morgan, J. D., De Marco, A. C., LaForett, D. R., Oh, S., Avankova, B., Morgan, W., & Franco, X. (2018). What racism looks like: An infographic. Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://fpg.unc.edu/publications/what-racism-looks-infographic

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2014). Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the developing drain (Working Paper No. 3). Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. https:// harvardcenter.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2005/05/Stress_Disrupts_Architecture_ Developing_Brain-1.pdf

Nepe, R., Panapa, W., & Jackson, L. (2021). Update on Manaaki Tairāwhiti and the navigators to the FVSV JV DCEs. Manaaki Tairāwhiti.

New Zealand Government. (2021a). Government offers formal apology for Dawn Raids.www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-offers-formal-apology-dawn-raids

New Zealand Government. (2021b). Te Aorerekura. The National Strategy to Eliminate Family Violence and Sexual Violence. https://tepunaaonui.govt.nz/assets/National-strategy/Finals-translations-alt-formats/ Te-Aorerekura-National-Strategy-final.pdf

New Zealand Government. (2022a). Government Data Investment Plan 2022 [Version 2.0]. www.data.govt.nz/leadership/data-investment-plan/

New Zealand Government. (2022b). New Zealand’s Fourth National Action Plan 2023-2024 [Draft for consultation]. https://ogp.org.nz/assets/New-Zealand-Plan/Fourth-National-Action-Plan/OGPNZ-draft- 4th-National-Action-Plan-24-November-2022.pdf

New Zealand Government. (2022c, May 19). The wellbeing objectives. NZ 2022 Budget. www.budget.govt.nz New Zealand Legislation. (2019). Public Service Legislation Bill, Government Bill 189-1. www.legislation.govt.nz/bill/government/2019/0189/latest/d795037e2.html

Nicholson-Crotty, S., Nicholson-Crotty, J., & Fernandez, S. (2016). Performance and management in the public sector: Testing a model of relative risk aversion. Public Administration Review, 77(4), 603–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12619

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach (pp. xii–xii). Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674061200

NZPC. (2015a). More effective social services [Final report]. www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Documents/8981330814/Final-report-v2.pdf

NZPC. (2015b). More effective social services: Cut to the chase. www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Documents/c31698bddb/social-services-final-report-cttc.pdf

NZPC. (2022a). A fair chance for all interim report. Breaking the cycle of persistent disadvantage [Interim report]. www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/InquiryDocs/EISM-Interim/Productivity-Commission-A-fair- chance-for-all-Interim-Report.pdf

NZPC. (2022b). The benefits of reducing persistent disadvantage [Research Note]. NZPC. www.productivity.govt.nz/inquiries/a-fair-chance-for-all/

NZPC. (2022c). The benefits of reducing persistent disadvantage [Working Paper].

NZPC. (2023a). A fair chance for all: Summary of submissions on interim report. www.productivity.govt.nz/ assets/Inquiries/a-fair-chance-for-all/Summary-of-submissions-Fair-Chance-for-All.pdf

NZPC. (2023b). Follow-on review—Frontier firms [Final Report]. www.productivity.govt.nz/inquiries/follow-on- review-frontier-firms/

NZPC. (Forthcoming). A quantitative analysis of disadvantage and how it persists in Aotearoa New Zealand [A supplementary report to the a fair chance for all inquiry]. www.productivity.govt.nz/inquiries/a-fair- chance-for-all/

OECD. (2016). Pisa 2015 results (volume i): Excellence and equity in education. www.oecd-ilibrary.org/ docserver/9789264266490-5-en.pdf?expires=1681953579&id=id&accname=guest&checksum= 5DDC7F0F5FC215B404D0FE7C967D7693

OECD. (2017). Systems approaches to public sector challenges: Working with change. OECD Publishing. https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/OPSI-Systems-Approaches.pdf

OECD. (2019a). How does the earnings advantage of tertiary-educated workers evolve across generations? https://doi.org/10.1787/3093362c-en

OECD. (2019b). OECD good practices for performance budgeting. https://doi.org/10.1787/c90b0305-en

OECD. (2022). Anticipatory innovation governance: Towards a new way of governing in Finland. https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/OECD-Finland-Anticipatory-Report-FINAL.pdf

OECD. (2015). PCSD Toolkit—Organisation for economic co-operation and development. www.oecd.org/governance/pcsd/toolkit/

OECD Secretariat, & Washington, S. (2018). Centre Stage 2: The organisation and functions of the centre of government in OECD countries. OECD. www.oecd.org/gov/report-centre-stage-2.pdf

Office for Disability Issues. (2019). Reports from Convention Coalition. www.odi.govt.nz/united-nations- convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/nzs-monitoring-framework/monitoring-reports- and-responses/reports-from-convention-coalition/

Oxford Martin Commission. (2014). Now for the long term: The report of the Oxford Martin Commission for future generations (pp. 59–64). http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1946756714523920

Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. (2021). Wellbeing budgets and the environment. A promised land? www.pce.parliament.nz/publications/wellbeing-budgets-and-the-environment/

Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. (2022). Environmental reporting, research and investment. Do we know if we’re making a difference? https://pce.parliament.nz/media/0qger2rr/environmental- reporting-research-and-investment-do-we-know-if-were-making-a-difference.pdf

Pawson, E. & The Biological Economies Team. (2018). The new biological economy. How New Zealanders are creating value from the land. Auckland University Press.

Pearce, J. (2011). An estimate of the national costs of child poverty in New Zealand. Analytica. https:// static-cdn.edit.site/users-files/82a193348598e86ef2d1b443ec613c43/an-estimate-of-the-costs-of-child- poverty-in-nz-10-august-2011.pdf?dl=1

Perret, C., Hart, E., & Powers, S. T. (2020). From disorganized equality to efficient hierarchy: How group size drives the evolution of hierarchy in human societies. Proc Biol Sci, 287(1928). https://doi.org/10.1098/ rspb.2020.0693

Petrie, M. (2021). Environmental governance and Greening Fiscal Policy. Government accountability for environmental stewardship. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83796-9

Petrie, M. (2022). Integrating economic and environmental policy. Policy Quarterly, 18(2), 10–17. https://doi. org/10.26686/pq.v18i2.7569

Pihama, L. (2017). Investigating Māori approaches to trauma informed care. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing, 2(3), 18–31.

Prickett, K. C., Paine, S.-J., Carr, P. A., & Morton, S. (2022a). A fair chance for all? Family resources across the early life course and children’s development in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Prickett, K. C., Paine, S.-J., Carr, P. A., & Morton, S. (2022b). A fair chance for all? Family resources across the early life course and children’s development in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Priest, N., Paradies, Y., Trenerry, B., Truong, M., Karlsen, S., & Kelly, Y. (2013). A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science & Medicine, 95, 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031

PSC. (2022a). Enabling active citizenship: Public participation in government into the future [Long-term insights briefing]. Te Kawa Mataaho Public Services Commission. www.publicservice.govt.nz/assets/ DirectoryFile/Long-Term-Insights-Briefing-Enabling-Active-Citizenship-Public-Participation-in- Government-into-the-Future.pdf

PSC. (2022b). Guidance: System Design Toolkit for shared problems. www.publicservice.govt.nz/guidance/ guidance-system-design-toolkit/

PSC. (2020). Public Service Act 2020 reforms [Guidance]. www.publicservice.govt.nz/guidance/public-service- act-2020-reforms/

Rangihau, J., Manuel, E., Brennan, H., Boag, P., Reedy, T., Baker, N., & Grant, J. (1988). Puao-te-ata-tu (Day break): The report of the Ministerial Advisory Committee on a Maori perspective for the Department of Social Welfare. Department of Social Welfare.

Raworth, K. (2018). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Review into the Future for Local Government. (2022). He mata whāriki, he matawhānui: Draft report.www.futureforlocalgovernment.govt.nz/assets/Reports/Draft-report-final.pdf

Robeyns, I. (2017). Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined (1st ed.). Open Book. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1zkjxgc

Rua, M., Hodgetts, D., Stolte, O., King, D., Cochrance, B., Stubbs, T., Karapu, R., Neha, E., Chamberlain, K., Te Whetu, T., Te Awekotuku, N., Harr, J., & Groot, S. (2019). Precariat Māori households today [Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga’s Te Arotahi Series Paper]. Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga - A Centre of Research Exellence. www.maramatanga.ac.nz/sites/default/files/teArotahi_19-0502%20Rua.pdf

Schakel, W. (2019). Unequal policy responsiveness in the Netherlands. Socio-Economic Review, 19(1), 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwz018

Schick, A. (1996). The spirit of reform: Managing the New Zealand state sector in a time of change [A report prepared for the State Services Commission and The Treasury]. State Services Commission, The Treasury. www.publicservice.govt.nz/assets/DirectoryFile/The-Spirit-of-Reform-Managing-the-New- Zealand-State-Sector-in-a-Time-of-Change.pdf

Scott, G. (2001). Public sector management in New Zealand: Lessons and challenges. New Zealand Business Roundtable. www.nzinitiative.org.nz/reports-and-media/reports/public-management-in-new-zealand/ document/76

Scott, R., & Boyd, R. (2022). Targeting commitment: Interagency performance in New Zealand. Brookings Institution Press, Ash Institute for Democratic Governance and Innovation. www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctv1f1d07x?turn_away=true

Scott, R. J., Donadelli, F., & Merton, E. R. (2022). Administrative philosophies in the discourse and decisions of the New Zealand public service: Is post-New Public Management still a myth? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 00208523221101727. https://doi.org/10.1177/00208523221101727

Scott, R. J., & Merton, E. R. K. (2022). Contingent collaboration: When to use which models for joined-up government (A. Whitford & R. Christensen, Eds.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009128513

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Russell Sage Foundation.

Shareef, J., & Boasa-Dean, T. (2020, September 27). An indigenous Māori view of doughnut economics. Doughnut Economics Action Lab. www.doughnuteconomics.org/stories/24

Sharma, S., Walton, M., & Manning, S. (2021). Social Determinants of health influencing the New Zealand COVID-19 response and recovery: A scoping review and causal loop diagram. Systems, 9(52). https://doi.org/10.3390/systems9030052

Shonkoff, J. P., Slopen, N., & Williams, D. R. (2021). Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the impacts of racism on the foundations of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42(1), 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-101940

Sibley, C. G., & Wilson, M. S. (2007). Political attitudes and the ideology of equality: Differentiating support for liberal and conservative political parties in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 36(2), 72–84.

Siebert, J., Bertram, L., Dirth, E., Hafele, J., Castro, E., & Barth, J. (2022). International examples of a wellbeing approach in practice. ZOE Institute for Future-fit Economies. https://zoe-institut.de/en/ publication/international-examples-of-a-wellbeing-approach-in-practice/

Social Wellbeing Agency. (2023, February). Reports [Publications]. https://swa.govt.nz/publication/reports/

Solar, O., & Irwin, A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health (Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper (Policy and Practice) No. 2). World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44489

South Auckland Social Wellbeing Board. (2023). South Auckland Social Wellbeing Board. https://saswb.com Spoonley, P., & Hirsh, W. (1990). Between the lines: Racism and the New Zealand media. Heinemann Reed. State Services Commission. (2007). Standards of Integrity and Conduct. New Zealand Government.www.publicservice.govt.nz/guidance/guide-he-aratohu/standards-of-integrity-and-conduct/

Stats NZ. (2021). Less than half of disabled people under the age of 65 are working. www.stats.govt.nz/news/less-than-half-of-disabled-people-under-the-age-of-65-are-working/

Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29, 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2009). Report by the Commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz- Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdf

Sundqvist, G., & Nilsson, M. (2017). Weaknesses and strengths of the Swedish model of governance for sustainable development. Sustainability Science, 12(4), 535–548.

Swartling, Å. G., & Lidskog, R. (2017). From government to governance for sustainable development: A review of concepts, theory and practice in Sweden. Journal of Cleaner Production, 163, S175–S184.

Sweden Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2022). Strategy for Sweden’s global development cooperation on sustainable economic development 2022–2026. Ministry for Foreign Affairs. www.government.se/ international-development-cooperation-strategies/2023/01/strategy-for-swedens-global-development- cooperation-on-sustainable-economic-development-20222026/#:~:text=The%20objective%20of%20 Sweden’s%20international,Agenda%20and%20the%20Paris%20Agreement.

Te Puna Aonui and Manaaki Tairāwhiti. (2022). Insights from a place-based approach. Case study: Manaaki Tairāwhiti. www.mt.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/documents/insights-from-a-place-based-approach-2022.pdf

Te Puni Kōkiri. (n.d.). Ngā Tini Whetū. Retrieved 14 April 2023, from www.tpk.govt.nz/en/nga-putea-me-nga- ratonga/whanau-ora/nga-tini-whetu-is-a-whanaucentred-early-support-pr/

Te Puni Kōkiri. (2016). The Whānau Ora Outcomes Framework: Empowering whānau into the future. Te Puni Kōkiri. www.tpk.govt.nz/docs/tpk-wo-outcomesframework-aug2016.pdf

Te Whatu Ora. (2023). Localities – Te Whatu Ora—Health New Zealand. www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/whats- happening/work-underway/localities/

The Auckland Co-Design Lab. (2021, November 24). Niho Taniwha. www.aucklandco-lab.nz/resources- summary/niho-taniwha

The Southern Initiative. (2017). Early Years Challenge: Supporting parents to give tamariki a great start in life [Summary Report]. https://knowledgeauckland.org.nz/media/1859/early-years-challenge-report-tsi- oct-2017.pdf

The Southern Initiative & Auckland Co-design Lab. (2022). Unleashing the potential of whānau centred and community led ways of working enhancing collective ownership and action [Report for Child Wellbeing and Poverty Reduction Unit, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, to support the review of the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy]. www.aucklandco-lab.nz/reports-summary/unleashing-the- potential-of-whnau-centred-and-locally-led-ways-of-working

The Southern Initiative & The Auckland Co-Design Lab. (2019). Learning in complex settings: A case study of enabling innovation in the public sector [Innovation Brief]. https://static1.squarespace. com/static/5f1e3bad68df2a40e2e0baaa/t/6066c8e7915769264f39f67c/1617348842242/ Learning%2BIn%2BComplex%2BSettings_InnovationBriefMay2019.pdf

The Treasury. (2012). Treasury’s advice on lifting student achievement in New Zealand: Evidence Brief. www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2012-03/sanz-evidence-mar12.pdf

The Treasury. (2021). The Living Standards Framework 2021. www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/tp/living- standards-framework-2021-html

The Treasury. (2022). Te Tai Waiora: Wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand 2022 [B.43]. www.treasury.govt.nz/ publications/wellbeing-report/te-tai-waiora-2022

Thom, R. R. M., & Grimes, A. (2022). Land loss and the intergenerational transmission of wellbeing: The experience of iwi in Aotearoa New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine, 296(114804). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114804

Trust Tāirawhiti. (2023). Tairāwhiti Wellbeing Survey. www.tairawhitidata.nz/

Tryggvadóttir, Á. (2021). Spending reviews: Towards best practices. OECD. www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/ spending-reviews-towards-best-practices.pdf

United Nations. (2021). Our common agenda—Report of the Secretary-General. www.un.org/en/content/ common-agenda-report/assets/pdf/Common_Agenda_Report_English.pdf

Waitangi Tribunal. (1998). Te Whānau o Waipereira Report. Waitangi Tribunal. Waitangi Tribunal. (1999). The Wananga Capital Establishment report (WAI 718). https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68595986/Wai718.pdf

Waitangi Tribunal. (2014a). He Whakaputanga me te Tiriti: The Declaration and the Treaty (WAI 1040). https://waitangitribunal.govt.nz/news/report-on-stage-1-of-the-te-paparahi-o-te-raki-inquiry-released-2/

Waitangi Tribunal. (2019). Hauora: Report on stage one of the Health Services and Outcomes Inquiry [Waitangi Tribunal Report Wai 2575]. https://waitangitribunal.govt.nz/inquiries/kaupapa-inquiries/ health-services-and-outcomes-inquiry/

Waitangi Tribunal. (2014b). Meaning of the Treaty. www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/treaty-of-waitangi/meaning- of-the-treaty/

Wallander, J. L., Berry, S., Carr, P. A., Peterson, E. R., Waldie, K. E., Marks, E., D’Souza, S., & Morton, S. M. B. (2021). Patterns of risk exposure in first 1,000 days of life and health, behavior, and education-related problems at age 4.5: Evidence from Growing Up in New Zealand, a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Pediatrics, 21(285), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02652-w

Warren, K. (2021). Designing a new collective operating and funding model in the New Zealand public sector [Working Paper 21/12]. Victoria University of Wellington. www.wgtn.ac.nz/ data/assets/pdf_

file/0011/1942751/WP-21-12-Designing-a-collective-operating-and-funding-model-in-the-New-Zealand- public-sector.pdf

Washington, S. (2021). Taking care of tomorrow today – New Zealand’s long-term insights briefings. The Mandarin. www.themandarin.com.au/162481-taking-care-of-tomorrow-today-new-zealands-long-term- insights-briefings/

Weijers, D. M., & Morrison, P. S. (2018). Wellbeing and public policy: Can New Zealand be a leading light for the ‘Wellbeing Approach’? Policy Quarterly, 14(4), 3–12.

Welsh Government. (2015a). Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. www.futuregenerations. wales/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WFGAct-English.pdf

Welsh Government. (2015b). Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015—Essentials guide. www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2021-10/well-being-future-generations-wales-act-2015- the-essentials-2021.pdf

Welsh Parliament Public Accounts Committee. (2021). Delivering for future generations: The story so far. https://senedd.wales/media/sjrp5vm0/cr-ld14223-e.pdf

Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency. (2022). Whānau Ora annual report 2020/2021. https://whanauora.nz/publications/woca-annual-report

White, J., Schmidt-McCleave, R., & Clarke-Parker, M. (2022). Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission: Brief of Evidence of Peter Stanley Hughes for institutional response hearing. www.abuseincare.org.nz/ assets/Uploads/Witness-Statement-of-Peter-Hughes-for-the-State-Institutional-Reponse-Hearing.pdf

Wilson, P., & Fry, J. (2019). Kia māia: Be bold—Improving the wellbeing of children living in poverty (NZIER Public Discussion Paper, Working Paper No. 2019/1). NZIER. http://hdl.handle.net/11540/10271

Wilson, P., & Fry, J. (2023). Working together: Re-focusing public accountability to achieve better lives [NZIER report to the New Zealand Productivity Commission]. NZIER. www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/ Documents/working-together-re-focussing-public-accountability-to-achieve-better-lives/NZIER- accountability-report-final.pdf

| |

Boxes

|

|

|

Box 1

|

Reducing persistent disadvantage could raise productivity and create substantial social and economic benefits for everyone

|

18

|

|

Box 2

|

Failing to provide effective and early support, especially in early childhood, can have long-term and intergenerational impacts

|

30

|

|

Box 3

|

Why addressing persistent disadvantage matters for the wellbeing of people, communities and society

|

40

|

|

Box 4

|

Embedding te Tiriti o Waitangi within the health sector

|

42

|

|

Box 5

|

Values filter information, impact our reasoning, influence intentions and determine actions

|

56

|

|

Box 6

|

Reforming the values for how the public service and government could work

|

58

|

|

Box 7

|

Swedish Government approach to long-term objective setting

|

60

|

|

Box 8

|

French “Green Budget”

|

63

|

|

Box 9

|

What is anticipatory governance?

|

71

|

|

Box 10

|

Key features of the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015

|

72

|

|

Box 11

|

Centrally enabled, locally led, whānau-centred approaches are under-resourced

|

84

|

|

Box 12

|

The Tairāwhiti “way of working”

|

88

|

|

Box 13

|

Impact – the pseudo-accountability trap

|

91

|

|

Box 14

|

“Backbone” functions

|

92

|

|

Box 15

|

Te Tokotoru: A systems response

|

110

|

|

Box 16

|

Manaaki coaches use what is being learned on the ground to change the system

|

116

|

|

Box 17

|

Creating a platform to share learning and building the capacity to learn across the early years system in South Auckland

|

116

|

|

Box 18

|

The Tairāwhiti Wellbeing Survey

|

129

|

| |

Figures

|

|

|

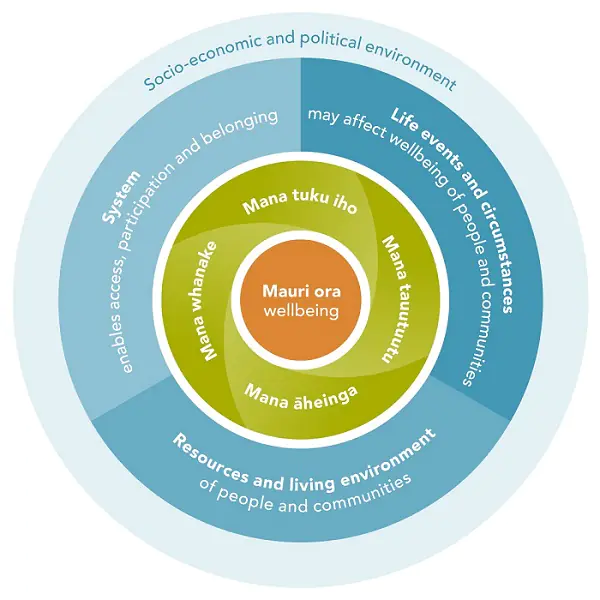

Figure 1

|

The New Zealand Productivity Commission’s “Mauri ora” approach

|

16

|

|

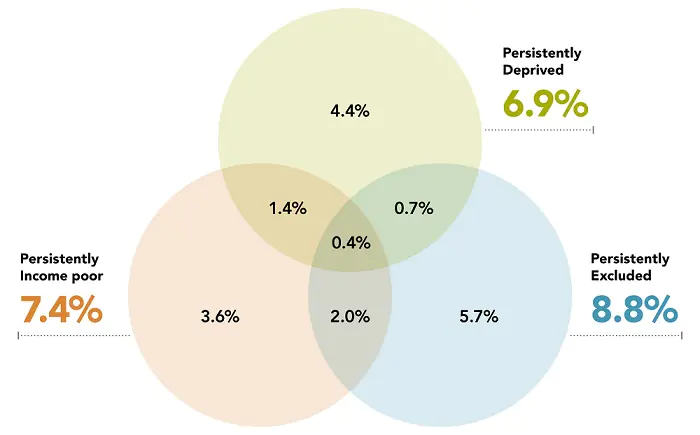

Figure 2

|

Persistent disadvantage across three domains (using seven measures) in 2013 and 2018

|

23

|

| |

Tables

|

|

|

Table 1

|

Inquiry research reports

|

19

|

|

Table 2

|

Percentage of population group experiencing persistent disadvantage in specified domains in both 2013 and 2018 (peak working age households)

|

24

|

|

Table 3

|

Contrasts between the historic and evolving emphasis of the system to enable it to deliver public value and to respond to complex contemporary challenges

|

38

|

|

Table 4

|

Principles to underpin a wellbeing approach in Aotearoa New Zealand

|

48

|

|

Table 5

|

Key whānau system measures used by Manaaki Tairāwhiti

|

113

|

|

Table 6

|

Examples of leadership and governance groups created to support whānau-centred, locally led and centrally enabled approaches

|

118

|

|

Table 7

|

Attributes of a learning system leadership function

|

122

|

|

Table 8

|

Recommendations roadmap

|

133

|

|

Table 9

|

Guidance for public bodies on wellbeing work

|

153

|