This chapter is in two parts. The first part presents high-level findings from our quantitative research. We then recap and build on the systems approach we took in the interim report, and we discuss systemic barriers constraining the public management system and how the system is evolving its ability to respond to complex societal challenges.

2. The dynamics and drivers of persistent disadvantage

Table of contents

- Foreword

- Terms of reference

- Acknowledgements

- Overview

- 1. This inquiry

-

2. The dynamics and drivers of persistent disadvantage

- Our quantitative research

- Too many New Zealanders experience persistent disadvantage

- The drivers of disadvantage are systemic

- Power imbalances create advantage for some people and compound disadvantage for others

- Discrimination and the ongoing impact of colonisation compound disadvantage

- Our public management system is part of the problem

- The public management system is evolving to respond to complex societal challenges

- 3. Our vision - a fair chance for all

-

4. Re-think the macro settings and assumptions of the public management system

- Macro settings increasingly emphasise wellbeing, but more actions are needed

- There are challenges with the way the current policy and public management system operates

- Broaden the values within the system to include the many dimensions of wellbeing and indigenous worldviews

- Set long-term wellbeing objectives

- Recognise the interests of future generations

- Establish a social floor

-

5. Re-focus public accountability settings to activate a wellbeing approach

- Accountability settings have a powerful influence over how the public management system operates

- Aotearoa New Zealand lacks the checks and balances found in other democracies

- There are three critical gaps in the design of our accountability system

- These gaps arise from the interplay of features that strongly incentivise certain ways of working

- Commission an independent, first-principles review of accountability settings, building on existing work

- Progress more immediate public accountability policy work

- Introduce legislation that imposes stronger accountability on ministers for addressing persistent disadvantage

- Support more locally led, whānau-centred and centrally enabled ways of working

-

6. Enable a public management system that learns and empowers community voice

- Current approaches to learning are not sufficient to drive improvement

- Learning needs to be locally led, whānau-centred and centrally enabled

- An ongoing focus on learning by doing and real-time feedback

- Learning needs to happen at all levels of the public management system

- A learning system can help the system focus on what matters to individuals, families, whānau, and communities

- Actively involve whānau and communities in innovation, learning and policymaking

- The learning system must enable two-way learning and accountability between communities and central government

- Build stronger connections with communities

- Create a leadership and stewardship function for learning in the public management system

- Establish a government-wide learning policy

- Invest in the capability and capacity of the learning system

- Invest in data collection to allow wellbeing and disadvantage to be measured over the life course and between generations

- 7. Conclusions

- Commonly used terms

- Appendix A: Well-being for Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 – Further details

- Appendix B: Public consultation

- References

Our quantitative research

Most reporting on disadvantage in Aotearoa New Zealand is based on cross-sectional data that does not indicate whether it is temporary or persistent. The Living in Aotearoa survey by Statistics NZ aims to provide more information on the persistence of income poverty and material hardship, but its results for the first three years will not be reported until 2024. This inquiry has therefore had to rely on available sources, which provide only limited longitudinal data.

As explained in Chapter 1, the inquiry defined persistent disadvantage as having three domains: being left out, doing without, and being income poor. We were only able to measure persistent disadvantage in two time periods (2013 and 2018), using seven measures from census data. The inquiry also analysed the factors contributing to temporary or persistent disadvantage by linking census data with Household Economic Survey data from 2015/2016 to 2020/2021.

We focused on households with at least one adult aged 25 to 64, which we refer to as “peak working age households”. Individuals in peak working age households who experienced disadvantage in at least one of the three domains in two consecutive time periods were considered to have persistent disadvantage.

More information on the datasets and methods used to measure persistent disadvantage, as well as the analysis of young and older households, is provided in our supplementary report to the inquiry A quantitative analysis of disadvantage and how it persists in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZPC, forthcoming).

Too many New Zealanders experience persistent disadvantage

Despite their innate strengths and the ability of people and communities to withstand life’s challenges, not everyone in Aotearoa New Zealand is experiencing mauri ora.

Close to one-fifth of New Zealanders experienced persistent disadvantage in both 2013 and 2018

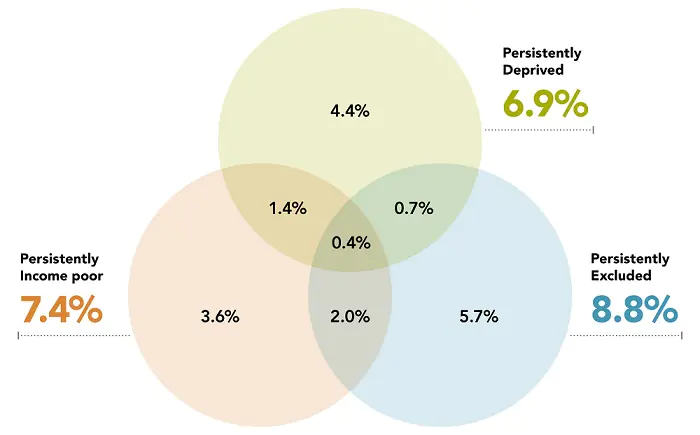

We found that approximately one in five New Zealanders (18.2% or 697,000) experienced persistent disadvantage in one or more domains in both 2013 and 2018. Around one in twenty New Zealanders (4.5% or 172,000) experienced complex and multiple forms of persistent disadvantage (in two to three domains).

The most common persistent disadvantage experienced was being left out (8.8% or 337,000), followed by being income poor (7.4% or 283,000) and then doing without (6.9% or 265,000).

Figure 2 Persistent disadvantage across three domains (using seven measures) in 2013 and 2018

Source: NZPC analysis of Census 2013 & 2018 for peak working age households.

Some groups experienced higher rates of persistent disadvantage

On average, current-day New Zealanders are healthier, better educated, have higher incomes, and live in communities with less crime than previous generations. However, this aggregate story conceals significant differences in wellbeing – demographically, geographically and intergenerationally (NZPC, 2022a; The Treasury, 2022).

As shown in Table 2, the proportions of renters in public housing (“public renters”), people from families with no formal (high school) qualifications, sole parents, and Pacific peoples who experienced persistent disadvantage in one or more domains were two to four times greater than the “average” Aotearoa New Zealand population. Between 60% and 70% of public renters and households with no high school qualifications experienced some form of persistent disadvantage. Note that these relationships should not be interpreted as group membership causing deprivation; for example, allocation of public housing is based on income, savings, and other need, so this relationship between disadvantage and public housing is true by design.

Although more households with Māori and people with disabilities experienced persistent disadvantage at rates higher than average peak working age households, Pacific peoples and sole parents had even higher rates. Asian peoples experienced being income poor or doing without at rates 1.5 times greater than the average peak working age households, but they were less likely to be left out or experience persistent disadvantage in two or all three domains.8

Finding 1

Approximately 697,000 New Zealanders experienced persistent disadvantage in one or more domains in both 2013 and 2018. A total of 172,000 people experienced complex and multiple forms of persistent disadvantage in two or three domains in both 2013 and 2018. Māori, people with disabilities, Pacific peoples, and sole parents experienced higher rates of persistent disadvantage compared with rest of the peak working age households in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Table 2 Percentage of population group experiencing persistent disadvantage in specified domains in both 2013 and 2018 (peak working age households (HH)

|

|

Population (%) | One domain in both years (%) | Two or more domains in both years (%) | Any type of disadvantage in both years (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public renters | 5.2 | 33.2 | 30.1 | 63.4 |

| No high school qualification in HH | 6.4 | 46.5 | 22.5 | 68.8 |

| Sole parents | 9.5 | 24.8 | 11.5 | 36.4 |

| Disability | 4.1 | 21.1 | 9.9 | 31.1 |

| Māori | 16.9 | 18.0 | 8.5 | 26.6 |

| Pacific | 9.0 | 31.1 | 14.6 | 45.7 |

| Asian | 17.7 | 15.8 | 3.8 | 19.5 |

| Total – peak working age HH | 100 | 13.7 | 4.2 | 18.2 |

Note: “Population” is the households with at least one adult aged 25–64 years (“peak working age households”).

Manukau (within the Auckland region) had the highest proportion of people experiencing persistent disadvantage in one or more domains, and the Wellington region, the South Island and Waitemata (within the Auckland region) had the smallest. The geographic distribution of persistent disadvantage we found followed a similar pattern of distribution to the New Zealand Deprivation Index,9 which ranks communities from the least to the most deprived, based on a set of nine census measures (Atkinson et al., 2019).

For many people, disadvantage does not persist

All of us experience challenges in our life that can temporarily impact our wellbeing and move us into mauri noho. For most of us these periods of disadvantage are relatively short: our analysis found that 45%–48% of working age New Zealanders experienced disadvantage at least once in a 5-year period, but for 60%–63% of them this may have been a temporary or one-off experience. For example, young people’s first jobs are typically at lower pay than they will earn in their later life, as they acquire skills and experience, and learn what employment best suits them. Many people can get themselves through a temporary period of disadvantage by drawing on their own resources, accessing support from family and friends and the local community, and from the Government (McLachlan et al., 2013; NZPC, 2022a).

The rate of disadvantage in Aotearoa New Zealand is fairly constant over time

We used the Household Economic Survey to examine trends in temporary disadvantage across the three domains over six years between 2015–2016 and 2020–2021. We found the rate of disadvantage, whether experienced in one domain or over more domains (being income poor, doing without or being left out), remained fairly consistent in that six-year period. We found that, generally, annually reported rates of disadvantage in any domain or combination of domains were at least twice the rates of persistent disadvantage we reported. This is consistent with an earlier New Zealand study using six years of data from the Survey of Family Income and Employment (Gunasekara & Carter, 2012). However, this finding is limited by data availability, and it may not hold over longer periods or, for example, through economic downturns.

Any experience of disadvantage negatively affects life satisfaction and wellbeing

Life satisfaction has been found to be a good indicator of subjective wellbeing. For example, De Neve et al. (2020) report life satisfaction ratings as being correlated to third-party reports and biomarkers of health, a good predictor of life expectancy, and highly reliable on retesting of the same populations.

As might be expected, we found that people with no temporary or persistent disadvantage have the highest life satisfaction scores of any group. Life satisfaction declines when disadvantage in any domain is experienced, and it decreases further if disadvantage is experienced in multiple domains or over longer time periods.

The drivers of disadvantage are systemic

We have taken a system-wide approach

Employment, education, housing and health are all social policy sectors which can make a direct difference in people’s lives. However, as required by the terms of reference of this inquiry, we have taken “a system-wide and whole-of-government perspective” and investigated the role of the public management system. Many submitters have recommended and supported this approach throughout the inquiry.

As described previously, there have been many reports and recommendations on how to address disadvantage, yet it persists at significant levels. The reason is partly a lack of political commitment, but even when there is political commitment, there are other factors at work – often within the public management system – which get in the way of following through on recommendations. As illustrated by the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care and the report of the Welfare Expert Advisory Group, actions by the public management system can create or exacerbate disadvantage, rather than reducing it, if decision-makers are not held to account and corrective actions are not promptly applied.

Although sector-specific policies have received attention on many occasions, there has been much less investigation on the role of the public management system itself in addressing persistent disadvantage.

The Commission, in its function as an independent advisor to the Government, is well placed to fill this gap.

We identified four barriers as underlying drivers of disadvantage

In taking a systems approach, our interim report recognised that findings such as communities experiencing higher rates of disadvantage are symptoms of deeper issues. We hypothesised four “barriers” as underlying drivers of disadvantage, and as factors that keep people trapped (NZPC, 2022). Generally, submitters endorsed those system barriers (NZPC, 2023a) with some, like the New Zealand Council of Christian Social Services, explaining how those barriers are observed in everyday work with clients.

Our members evidence these barriers through the experiences their clients face in interacting with systems and services designed to offer help to those experiencing disadvantage. More and more kaimahi time is being spent advocating for clients who are weary, disillusioned, and desperate as a result of their mana being diminished in their attempts to access the support they are entitled to. (sub. DR120, p. 2)

These submissions, and the feedback we got from many officials at workshops, give us confidence to reaffirm our view that those barriers are holding back the initiatives and changes needed to address persistent disadvantage, and are keeping people trapped. The following sections discuss these barriers in more detail, but first we provide high-level comments on the nature of the barriers and relationship between them. The first two barriers are as follows.

- Power imbalances – policy and service responsiveness is strongly skewed toward people who have political, social or economic power, which entrenches the cycle of disadvantage.

- Discrimination and the ongoing impact of colonisation – people of European descent became the ethnic majority and instituted assimilation and land alienation policies that continue to disadvantage Māori. Institutional racism and discrimination against other groups is also prevalent, including towards Pacific peoples, women, migrants, LGBTQ+ communities, sole parents and people with disabilities.

Power imbalances, discrimination, and the ongoing impact of colonisation exist within our wider society. They provide the economic and social context for both advantage and disadvantage and can be reflected and amplified by the public management system. For a high-level example, historic and contemporary breaches of te Tiriti o Waitangi (te Tiriti) by the Crown are instituted through the public management system. Discrimination also reflects societal power dynamics, making this barrier a subset of power imbalances. As discussed in following chapters, these barriers can be addressed by broadening the values of the system and including the voices of disadvantaged people in decision making, along with better operationalising te Tiriti and international obligations. The second two barriers are as follows.

- Siloed and fragmented government – disadvantage is a complex problem, but our public services are focused on providing standardised services to individual people through ministries and agencies focused on separate sectors.

- Short-termism – our systems are too focused on the immediate issues of the day, at the expense of addressing long-term challenges or anticipating what might lie around the corner.

These barriers relate more closely to the design and operation of the public management system. Silos and fragmentation get in the way of the whole-of-government, whānau-centred, and locally led approaches that are needed, and which have been shown to be effective in addressing disadvantage. Silos and fragmentation can be addressed through new models of public management that emphasise the co-creation of support through networks and partnerships, such as Whānau Ora.

Short-termism reflects that the attention of voters and politicians is more easily captured by the immediate, certain and visible nature of the present, at the expense of meeting long-term and future challenges. This bias must be balanced in recognition of the intergenerational impacts of persistent disadvantage, and to achieve the long-term commitment needed to address persistent disadvantage.

The complex interactions between these barriers, the causes and impacts of disadvantage, and the influences and tensions within the public management system are explored diagrammatically in a companion report, Causal diagrams to support ‘A fair chance for all’ (Connolly, 2023). Developing these diagrams helped the inquiry team to develop an integrated picture of the interconnected elements contributing to people’s persistent experience of disadvantage.

Finding 2

The drivers of disadvantage are systemic. Broader societal barriers are reflected in the public management system. Power imbalances, discrimination, and the ongoing impacts of colonisation form part of the economic and social context for both advantage and disadvantage in Aotearoa New Zealand. In addition, siloed and fragmented government and short-termism reflect well-known challenges that the public management system has been grappling with for decades.

Power imbalances create advantage for some people and compound disadvantage for others

Power is the ability to act on or influence something. Political power is the ability to shape the outcome of contested policies, including through shaping the political agenda and public opinion. People with more power have more influence on the design of policies and services, which become more responsive to, and better meet their needs. At the extremes, wealthy people can have a greater influence over important decisions (Gilens & Page, 2014; Schakel, 2019), and powerful people can get direct access to politicians to influence policy (Edwards, 2022; Espiner, 2023a, 2023b), but vulnerable groups feel invisible (NZPC, 2023a).

Social and economic differences drive power imbalances

In Aotearoa New Zealand, income and wealth are very unevenly distributed (T. Hughes, 2022b), and demographic and geographic inequities are evident across our education, housing, justice, welfare and health sectors. These social and economic differences have a significant and direct influence on the extent to which particular groups of people are more or less likely to experience disadvantage in their lives. Power imbalances mean the voices of people and communities more likely to experience disadvantage are not listened to or heard; their needs are less likely to be understood or met; and, consequently, they continue to experience inequitable outcomes.

There are many factors within the influence of government policy and the design of public services that can protect people against becoming disadvantaged or persistently disadvantaged. As set out in our interim report (Finding 4.5), protective factors include adequate income, housing, health and social connection, cultural identity and belonging, knowledge and skills, access to employment, stable families, and effective government policies and supports (NZPC, 2022a). For example, getting a good start in life is critical, as childhood adversity can impact social and cognitive development (Advisory Group on Conduct Problems, 2009; Center on the Developing Child, 2010; Wallander et al., 2021). The effects of a disadvantaged start are reversible through effective support during pregnancy and childhood (Bush et al., 2023; McEwen & McEwen, 2017), but failure to provide support through equitable health, education and housing policies can have adverse life course and intergenerational impacts (see Box 2). Yet it can be difficult for governments to prioritise such polices if “advantaged” people already have protective factors, disadvantaged people lack voice, and decision-makers lack diversity or understanding of the lives of people experiencing disadvantage.

The system reinforces advantage and disadvantage

The system is often not responsive to people and groups experiencing disadvantage, and who struggle to get the support they need. For example, Māori have higher rates of many diseases, less access to services, and they benefit less from the treatments they receive (HQSCNZ, 2019). This means different people can experience the same system very differently and can have very different, yet legitimate perspectives on the same issue. The system cannot deliver a “fair chance for all” when decisions are based on the experiences of people who are advantaged, and when the system fails to include the voices of disadvantaged groups.

The health sector has long recognised that power distribution in society has a central role in generating patterns of inequitable outcomes. In 1971, a doctor in the United Kingdom named inequity in the provision of healthcare “the inverse care law”, observing the double injustice that disadvantaged populations are more susceptible to illness than socially advantaged people, and they need more healthcare than advantaged populations yet receive less (Cookson et al., 2021). In Aotearoa New Zealand, this inequitable access to healthcare is reflected in the health outcomes of population groups that experience high rates of disadvantage (Baker et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2021).

Tertiary education and high literacy and numeracy skills are strongly associated with better labour-market and social outcomes (OECD, 2019a). Although education could substantially reduce persistent disadvantage (Llena-Norzal et al., 2019; The Treasury, 2012), socioeconomic background has a pervasive impact on student achievement and participation in higher education (OECD, 2016). People whose parents are not tertiary educated are under-represented in tertiary education and are more likely to leave the education system at each educational milestone (OECD, 2019a). Families experiencing persistent disadvantage may lack the resources for their children to fully participate in education, and children can experience ableism, bullying (OECD, 2019a) and racism at school.

Some teachers are racist. They say bad things about us. We’re thick. We smell. Our uniforms are paru [dirty]. They shame us in class. Put us down. Don’t even try to say our names properly. Say things about our whānau. They blame us for stealing when things go missing. Just ‘cause we are Māori. (Bishop & Berryman, 2006, p. 1)

In OECD countries, highly educated people live an average six years longer than less educated people, with higher employment rates and lower job insecurity (Llena-Norzal et al., 2019). In Aotearoa New Zealand, our schooling system is less effective for people from disadvantaged backgrounds than in comparable OECD countries (OECD, 2019a). Māori and Pasifika peoples are under-represented in university student and staff numbers, especially in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM); they experience marginalisation, racism and exclusion, and staff experience pay and promotion inequities (McAllister, 2022). Until these inequities are resolved, health and education systems in Aotearoa New Zealand are more likely to reinforce advantage, rather than acting as interventions through which equity can be achieved.

Power imbalances thwart trust and drive disengagement and further disadvantage

Power imbalances also thwart trust, which is a critical ingredient in reaching people who have disengaged due to negative past experiences with “the system”. Disengagement drives further disadvantage and exacerbates the consequences of disadvantage (Haemata Limited, 2022b).

For those without support, or who lack confidence or sufficient communication skills, this power imbalance presents as a lack of care and empathy and can mean they are not able to engage with the public services they may require (ibid, p. 15).

If people experiencing disadvantage do not get early and effective support, their problems persist, which further restricts their choices and opportunities, and worsens their situation. They may then experience persistent loss of wellbeing, increasing vulnerability to further disadvantage. This can also be transmitted to future generations, as highlighted in Box 2.

|

Box 2 Failing to provide effective and early support, especially in early childhood, can have long-term and intergenerational impacts |

|---|

|

Persistent disadvantage can lead to toxic stress for both children and adults, which can have long-term negative impacts on individual and whānau health and wellbeing, and can be transmitted to future generations, as the stress affects the environment within which children live and grow (Bush et al., 2023; McEwen & McEwen, 2017). The life course and intergenerational impact of poverty and adversity were also highlighted by submitters (Poverty Free Aotearoa, sub. DR139; David King, sub. DR155). Parents and whānau experiencing persistent disadvantage have fewer resources to invest in their children to keep them healthy and help them develop, and resource scarcity can cause overwhelming stress (Knowles et al., 2016; Ministry of Social Development, 2018; The Southern Initiative, 2017). In addition, studies have shown that toxic stress can lead to changes in DNA, affecting the expression of genes that regulate stress and emotional responses – potentially leading to increased risk of mental health issues, substance abuse, and other health problems in future generations (McEwen & McEwen, 2017). “Toxic stress” is a term used to describe a chronic stress response that occurs when a person experiences ongoing adversity, such as abuse, neglect, or poverty, without adequate support (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2014). It can impact the development of a child’s brain, immune system, and other organ systems, leading to physical and mental health problems throughout their life (ibid.). Toxic stress can also have negative impacts on social and emotional development, including the ability to form healthy relationships and manage emotions (ibid.). The impacts of toxic stress can be particularly severe in childhood, as this is a critical period for brain development (ibid.). Critically, many of these effects are reversible through effective support during pregnancy and childhood (Bush et al., 2023; McEwen & McEwen, 2017). Several submissions highlighted the complex and unique position of children in relation to persistent disadvantage (sub. DR90, 100, 107, 117, 119, 124, 127, 129, 139 and 140). Several submissions agreed with the finding that early intervention to prevent disadvantage during a child’s early years is critical to breaking the cycle of disadvantage (sub. DR100, 124 and 140). A recent New Zealand study identified children who had limited access to resources (such as low income, parents not in employment and living in an overcrowded home) during their early childhood (Prickett et al., 2022a). The parents of the children who experienced access to below-average levels of resources reported that their children had high levels of depression, anxiety, and aggressive behaviours during their early childhood. The children also had less well-developed skills needed to think, learn, remember, reason, and pay attention (ibid.). These skills are critical to education and skill development, subsequently to employment opportunities and earning potential. |

Power imbalances are felt within all levels of the public management system

As described in Chapter 5, the public sector can be very hierarchical, constraining what is perceived as “legitimate action” by public servants. Many public servants we spoke to expressed the discomfort they experience when existing practices and processes do not allow them to take the actions needed to make a difference, but they do not feel supported to express their opinions or take risks. For some, “workarounds” become a standard part of how they work, exposing them to personal risk if things go wrong. Navigating such situations requires great courage and tenacity, but often leads to decreased motivation and commitment, and potentially burnout.

Some public servants also expressed that power and responsibility lies largely with ministers or with voters. But this downplays the significant power that public servants (especially in senior roles) have to make decisions that impact the public’s wellbeing. It also ignores the stewardship role, which obliges the public service to focus on what is important in the medium-to-long term, not just in the current electoral cycle. In Foucault’s distributed theory of power, power exists only when it is put into action, even if “integrated into a disparate field of possibilities brought to bear upon permanent structures” (Foucault, 1982, p. 788).10 This means it is critical for public servants to identify the actions that are available – whether to them, other agencies, or within society – even if these actions may not be easy or have a large or immediate impact. Improvement generally requires action – exercising power through the actions that are available. The changes recommended in this report are intended to make this easier. Although public servants will still need both courage and support, we consider that the recommendations we make in this report will reduce the need for individuals to use risky workarounds – such as providing services to people who do not meet eligibility criteria.

Discrimination and the ongoing impact of colonisation compound disadvantage

Discrimination refers to the unjust or prejudicial treatment of individuals or groups based on certain characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, age, disability, or other personal traits. Discrimination can take many forms, including but not limited to verbal or physical abuse; exclusion from social, economic, or political opportunities; differential treatment in hiring, promotions, or access to services; and other forms of bias or unfairness. Discrimination can occur at the individual or systemic level and is a violation of basic human rights and dignity.

Discrimination makes it harder for affected groups of people to access the same opportunities and results in inequitable outcomes

Women, people with disabilities, Māori, and Pacific peoples experience employment and wage “gaps”. In 2022, the gender pay gap between men and women in Aotearoa New Zealand was 9.1%. The pay gap for people with disabilities was 11.5% in 2021, compared with people without disabilities (Statistics NZ, 2021). In 2021, the pay gap between Māori and Europeans was 19% and 1% for men and women respectively, and 24% and 14% for Pasifika men and women respectively (Cochrane & Pacheco, 2022). Analysis by the Human Rights Commission (2022) found that only 27% of the pay gap for Pasifika men, and 39% of the gap for Pasifika women could be explained by differences in observable factors such as job characteristics and education.

This research provides further evidence about what we’ve long suspected – the bulk of the Pacific Pay Gap can’t be explained and is at least partly due to invisible barriers like racism, unconscious bias and workplace discriminatory practices. (Saunoamaali’i Karanina Sumeo, Equal Employment Opportunities Commissioner)

Institutional or systemic racism is destructive

Institutional (or systemic) racism is “distinguished from the explicit attitudes or racial bias of individuals by the existence of systematic policies or laws and practices that provide differential access to goods, services and opportunities of society by race” (Morgan et al., 2018). Institutional racism is an outcome of organisational policies and practices, including those of government agencies, and can be unintentional or unconscious.

Although institutional racism can be unintentional, it has been described as the most insidious and destructive form of racism (Haemata Limited, 2022a; Rangihau et al., 1988). Institutional racism against Māori is well documented in Aotearoa New Zealand. For example, the Waitangi Tribunal11 has highlighted systemic underfunding of Māori tertiary education and health providers (Waitangi Tribunal, 1999, 2019). Discrimination and institutional racism compound the impact of colonisation, which deliberately alienated Māori from their lands, culture and language (Rangihau et al., 1988; Thom & Grimes, 2022).

Pacific peoples have a different history, albeit with similar themes of being harmed and disadvantaged by both deliberate and unconscious racist policies and practices. Whole communities were terrorised by police during the dawn raids of “Operation Pot Black” in the 1970s (New Zealand Government, 2021a). Pacific people migrated to Aotearoa New Zealand during the preceding economic boom but were then used as scapegoats during a downturn (Spoonley & Hirsh, 1990). In 2021 the Government formally apologised to the people and communities impacted by the dawn raids (New Zealand Government, 2021a).

The cumulative and intergenerational effects of colonisation and racism present significant barriers to wellbeing for Māori and Pacific peoples today

These impacts are insidious when people experiencing racism accept the negative assumptions and lack of access to opportunities as the norm. For example, low expectations from teachers can create a “downward spiralling, self-fulfilling prophecy of Māori student achievement and failure” (Bishop et al., 2003, p. 2). Poor education outcomes for Māori students then lead to socioeconomic disadvantage, disillusion and anger (Waitangi Tribunal, 1999, p. 31). Māori and Pacific peoples may also be part of other groups that face discrimination and higher rates of disadvantage – women, people with disabilities, or gender or neuro-diverse – and therefore face additional barriers.

Culture and identity are central to both Māori and Pacific models of wellbeing (Haemata Limited, 2022a; McMeeking, Kahi, et al., 2019; Ministry for Pacific Peoples, 2022). Iwi that suffered a higher proportion of land loss at the hands of the Crown have lower contemporary rates of te reo Māori proficiency and cultural connection than iwi that retained more land at the end of the 19th century (Thom & Grimes, 2022). The systemic oppression experienced globally by indigenous peoples over generations manifests as historic and intergenerational trauma (ibid.; Aguiar & Halseth, 2015; Bishop et al., 2003, p. 2). Māori have experienced this trauma in distinct ways, from the ongoing impacts of the land alienation and cultural assimilation policies that were part of colonisation and the resulting loss of connection to place, culture and language, to institutional racism, discrimination, and negative stereotyping (Haemata Limited, 2022a; Pihama, 2017; Waitangi Tribunal, 1999).

The impacts of historical and intergenerational trauma can include high rates of addiction and mental health issues, violence, poverty, and a loss of trust in institutions. Recognising and addressing the ongoing impacts of historical and intergenerational trauma is essential to promoting healing, reconciliation, and the wellbeing of indigenous peoples (Aguiar & Halseth, 2015; Thom & Grimes, 2022). The particular experience of trauma for Māori can impact their self-worth, their identity, and their aspirations for the future, and it can become embedded across generations (Haemata Limited, 2022a). A person’s sense of identity and belonging can influence their behaviour, such as their ability to take advantage of opportunities and their tolerance for risk.

Being connected with one’s culture facilitates a sense of worth, tradition, confidence, and knowledge transmission which participants agreed lead to Māori feeling a greater sense of expectation on them to succeed and create something for themselves and for their mokopuna. (Haemata Limited, 2022c, p. 1)

It is critical that historical and contemporary trauma is recognised, and that support is effective and not retraumatising (Pihama, 2017). If this does not happen, then Māori can become disengaged from public services and not seek the support they need. For example, one participant in a recent wānanga discussed how “this mindset has caused her whānau to remain both in unsafe housing and refusing financial assistance” (Haemata Limited, 2022c, p. 10).

The long-term adverse impacts of stress and trauma caused by discrimination against already vulnerable communities is concerning (for example see Priest et al., 2013; Shonkoff et al., 2021). Several submissions to this inquiry highlighted the struggles various minority groups experience in being seen, heard, and supported. This includes children, people of Asian descent, refugees, neurodiverse people, LGBTQ+ people, older people, people with mental health and addiction issues, people with limited English, and people with disabilities (sub. DR097, 100, 101, 108, 109, 122, 135, 142, 145 and 152). As expressed by Parents with Vision Impaired Children in their submission, the lack of access to timely, effective services, sensitive to the needs of vulnerable people is another factor that can exacerbate disadvantage.

So many of our families are tired of piecemeal half-assed approaches that “tinker at the edges” and don’t address the challenges and barriers they and their disabled child face. (sub. DR97, p. 3)

Discrimination and the ongoing impacts of colonisation and power imbalances were barriers that strongly resonated with submitters (NZPC, 2023a), as noted in the submission from Social Service Providers Aotearoa.

The acknowledgement of the ongoing impacts of colonisation, structural and institutional racism, power dynamics among other things in this report is important, because it gives us a start point from which to make progress. It is also important, given that these factors and breaches of te Tiriti o Waitangi underpin and drive many of the inequities experienced by some of our whānau Māori today, and the stratification of our society. Acknowledging these underlying drivers is part of what enables action to get to a better place as a nation and within our communities. (sub.DR129, p. 5)

Our public management system is part of the problem

Our public management system encompasses public service agencies and their functions and mandates; the public sector’s relationships and partnerships; policymaking and service-delivery processes and practices; and system-wide governance, accountability, and funding arrangements. This system largely determines who gets to be part of setting high-level public policy goals, what information or evidence is generated and drawn on, which approaches and programmes receive funding, what the eligibility criteria are, how people in the system are held to account, and what information is used to improve the system settings over time.

Governments and the public service have commissioned many reviews and studies over the past 50 years and implemented various reforms related to how the system operates to improve the lives of New Zealanders. Common and repeated findings of reviews include the need for greater coordination and cooperation across government sectors and between agencies providing services to the same people; that the system is failing to meet performance and cost expectations; and that the system is failing particular groups of people, including Māori, Pacific peoples and people with multiple complex needs (NZPC, 2022a).

Above, we have described power imbalances, discrimination, and the ongoing impacts of colonisation as broader societal barriers, which are also reflected in the public management system.

In this section, we describe the barriers of siloed and fragmented government and short-termism as expressed in the design and operation of the system. These reflect well-known challenges that our public management system has been grappling with for decades, along with other western democracies (Boston et al., 2020; Carey & Crammond, 2015; Eppel & O’Leary, 2021). Underlying this challenge is a transition from governments focusing on the efficient delivery of public goods and services, to governments taking a more connected and integrated approach to citizens’ needs and responding to complex, long-term societal challenges (Lodge & Gill, 20 1; OECD, 2017; R. J. Scott et al., 2022).

Short-termism is reflected in structure and incentives of government

Short-termism is a human “presentist bias”. Although people do care about the future, the attention of both voters and politicians is more easily captured by immediate issues at the expense of addressing long-term and future challenges. In contrast to the immediate, certain and visible nature of the present, the future is less certain, tangible and visible (Boston, 2021a).

Aotearoa New Zealand has protected longer-term interests in financial sustainability and monetary policy through the Public Finance Act 1989 and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act 2021. In addition, the Public Service Act 2020 requires agencies to produce Long-term Insights Briefings every three years. However, our Parliament lacks sufficient oversight and scrutiny arrangements to balance against the bias towards short-termism (Boston et al., 2019). Effective action on complex, long-term and intergenerational issues will be limited if the tendency to prioritise immediate and short-term issues is not sufficiently balanced.

Silos and fragmentation influence the design and operation of the public management system

Addressing “complex issues that span agency boundaries” and providing “wraparound services based on New Zealanders’ needs” were aims of recent reforms establishing a new Public Service Act in 2020 and making updates to the Public Finance Act 1989 (New Zealand Legislation, 2019, pp. 1–2).

The [previous State Services Act] was designed to address problems that existed at the time it was passed, mostly problems of bureaucratic over-centralisation and of lack of responsiveness to ministers. Arrangements for working as a system were not a priority to its designers. To oversimplify, the assumption behind the [Act] was that if each department just did its own prescribed job then the sum total of activity would be a well-functioning system. Peter Hughes, Public Service Commissioner (P. Hughes, 2019)

The Public Service Act 2020 and Public Finance Act 1989 are at the heart of the public management system, as they set out how the public service operates and how funding works. Recent changes to these instruments have started to adapt the system in recognition of the need to address complex challenges. However, there remains a strong vertical accountability to individual ministers and separate, specialised agencies and functions. As a result, silos and fragmentation can influence the way the public management system is designed, and how it operates.

These core elements reflect intentional design choices introduced by the New Public Management reforms of the late 1980s and early 1990s.12 These reforms were focused on delivering public services more efficiently and they were inspired by the perceived inefficiency of government compared to the perceived efficiency of markets and firms incentivised to satisfy “customers” (Schick, 1996, p. 18). The public management system was structured into smaller single-purpose agencies, and policy and operational functions were also separated (Chapman & Duncan, 2007; Eppel & O’Leary, 2021). This decentralised structure was coupled with an emphasis on top-down and individual accountability, especially the accountability of chief executives to ministers.

By the end of the 1990s, the limitations of New Zealand’s NPM-type reforms were widely recognized, particularly how the funding and accountabilities of organizational silos and fragmentation of services, created and reinforced by the reforms, hindered collaboration. (Eppel & O’Leary, 2021, p. 52)

A top-down approach may be a good match when efficient delivery of separately delivered and standardised services is needed, but people experiencing persistent disadvantage need tailored and joined-up services , as well as supporting community infrastructure (see Chapter 5). Arrangements such as restrictive contracts and onerous performance measurement that drive standardisation have also been identified as critical barriers to sustainable long-term change (McMullin, 2023).

In particular, our assessment is that New Zealand’s public funding and accountability settings are stifling the uptake of collective, preventative and long-term approaches to addressing persistent disadvantage, including support for Māori and locally led, whānau-centred initiatives (Controller and Auditor-General, 2023; Fry, 2022; 2015; NZPC, 2022a).

The public management system is evolving to respond to complex societal challenges

New models of public management that emphasise the co-creation of services through networks and partnerships are emerging and beginning to be taken up (Brandsen et al., 2018; Dormer & Ward, 2018; Lodge & Gill, 20 1; McMullin, 2023; Scott et al., 2022). This is an international trend that is evident in recent changes to the Public Service and Public Finance Acts, to enable new organisational forms for horizontal governance. It is also reflected in earlier initiatives, such as Whānau Ora, that prioritise the voice, needs and aspirations of people experiencing disadvantage in the design and provision of services. As discussed in the next chapter, this shift is also seen in the growing emphasis on the wellbeing of citizens.

System change often starts with emergent ideas growing within and co-existing (including in conflict) with the dominant system (noting it can also result from external pressures). In their analysis of the evolution of Aotearoa New Zealand’s public management system, Scott et al (2022) found that the Public Service Act is simultaneously reasserting and protecting historic characteristics while pushing toward something new. This finding is consistent with our observation that recent changes are an evolution, but more is needed to enable a connected and integrated response to address persistent disadvantage.

… the Act prioritises horizontal coordination, but does so in a way that privileges hierarchical structures and takes a conservative understanding of leadership as top tiers, rather than a more complex (and post-NPM) view that recognises the value of leadership qualities at all levels. (Scott et al., 2022, p. 1)

Although recent changes to the Public Service Act are aimed at encouraging cross-agency work and perspectives, they remain within a system optimised for the efficiency of “vertical” decision making and individual accountability (Scott & Merton, 2022, pp. 1–2). Hierarchies are more efficient for coordinating large groups of people to do relatively simple tasks, in which time is better spent carrying out the tasks than negotiating and maintaining group consensus (Perret et al., 2020). In contrast, “horizontal” consensus building and collective accountability can be viewed as inefficient (Scott & Merton, 2022, pp. 1–2).

Vertical organising can work well for relatively simple, one-size fits all or “technical” problems, but when situations become complex, responsibility shifts beyond the scope of individual organisations, and the importance of learning and sharing learning increases. Organisations designed to work individually lack the necessary access to information, tools, techniques, and culture to learn together. This makes them unable respond effectively to complex challenges, and to act collectively in the ways that people experiencing persistent disadvantage need them to.

Horizontal or collaborative organising requires more complex organisational forms and practices (Eppel & O’Leary, 2021, p. 15), including hybrid arrangements that draw on the strengths of top-down and bottom-up approaches (Carey & Crammond, 2015, p. 6). Connected, cross-agency working is also more resource intensive (Carey & Crammond, 2015). As discussed in both Chapters 5 and 6, organisations seeking to address complex challenges must develop different practices and cultures to distribute and coordinate – rather than concentrate – power, responsibility, resources and learning. The incompatibility between standard organisational approaches, and processes and practices needed to address disadvantage has been highlighted in the Auditor-General’s reports into how well public organisations are supporting Whānau Ora and whānau-centred approaches.

...since Whānau Ora was introduced, concerns have been consistently raised about how well public organisations are understanding, supporting, and learning from it. There have also been concerns about whether public organisations have adapted their systems and processes to enable whānau-centred ways of working (for example, by changing their funding, contracting, and reporting requirements).

…Overall, the compounding effect of the lack of clear expectations for public organisations and the barriers created by some public sector processes and practices means that Te Puni Kōkiri has made limited progress on its strategic focus area of expanding the use of whānau-centred approaches by public organisations. (Controller and Auditor-General, 2023, pp. 3–4)

Because responsibility for complex challenges sits beyond the scope of any single organisation, responding effectively requires accessing shared information and resources, working with ambiguity and uncertainty, building shared goals, and innovating across networks of people and organisations. Individual decision making (including by ministers) might be efficient in the short term, but it is not appropriate or effective when responding to shared goals.

In Table 3 we contrast the historic and emerging emphasis of the public management system. The intent of the “shifts” we set out in Chapters 4, 5 and 6 of this report is to reinforce the emerging emphasis on delivering public value rather than public goods, and to enable the public management system to better respond to complexity.

Table 3 Contrasts between the historic and evolving emphasis of the system to enable it to deliver public value and to respond to complex contemporary challenges

| Government objectives | Historic emphasis of the system | Emerging emphasis of the system | Shifts required to reinforce emerging emphasis |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Focus of the public management system |

Government seeks to replicate market-driven incentives in the provision of public goods and services, namely:

|

Government strives to deliver “intergenerational” public value, through:

|

|

|

Governance and coordination |

Governance and coordination through vertical hierarchies emphasising responsiveness to ministers and chief executives. |

Governance and coordination through vertical and horizontal networks and partnerships, leading to:

|

|

|

Accountability and performance |

Performance standards drive individual accountability, through:

|

Citizen- and community- centred focus and “locally led, centrally enabled”, leading to:

|

|

Source: Table adapted from Scott et al. (2022), and draws on analysis by Lodge & Gill (2011).

8. Due to data limitations, we regret that we were unable to break these broad categories down into more appropriate subgroups.

9. The New Zealand Deprivation Index (NZDep) is a socioeconomic deprivation index derived from a range of Census 2013 and 2018 measures including low-income household, no internet access in household, people with no job, people with no qualifications, overcrowded housing, damp and/or mouldy housing, people living in households receiving means-tested benefits, sole parent households, or those not living in their own home. NZDep is based on meshblocks in 2013 and reformulated as “statistical area 1” (comprised of one or more meshblocks with a maximum population of 500) in 2018, to divide the country into 10 equal parts or “deciles”. Hence, there will always be “most deprived” deciles (10) and “least deprived” deciles (1). A fuller explanation of the NZDep 2013 and 2018 is found at Otago NZDep, along with interactive maps of neighbourhoods across Aotearoa New Zealand.

10. Michael Foucault’s analysis of power emphasises the importance of understanding the complex ways in which power operates in society, and the role of power in shaping individuals and their interactions with others.

11. The Waitangi Tribunal is a permanent commission of inquiry that makes recommendations on claims brought by Māori relating to Tiriti breaches by the Crown.

12. New Public Management is a public sector management philosophy that aims to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of public services by adopting private sector management practices.