Abramovitz, M. (1956). Resource and output trends in the United States since 1870. The American Economic Review, 46(2), 5–23.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown. Acemoglu, D., & Zilibotti, F. (2001). Productivity differences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 563–606.

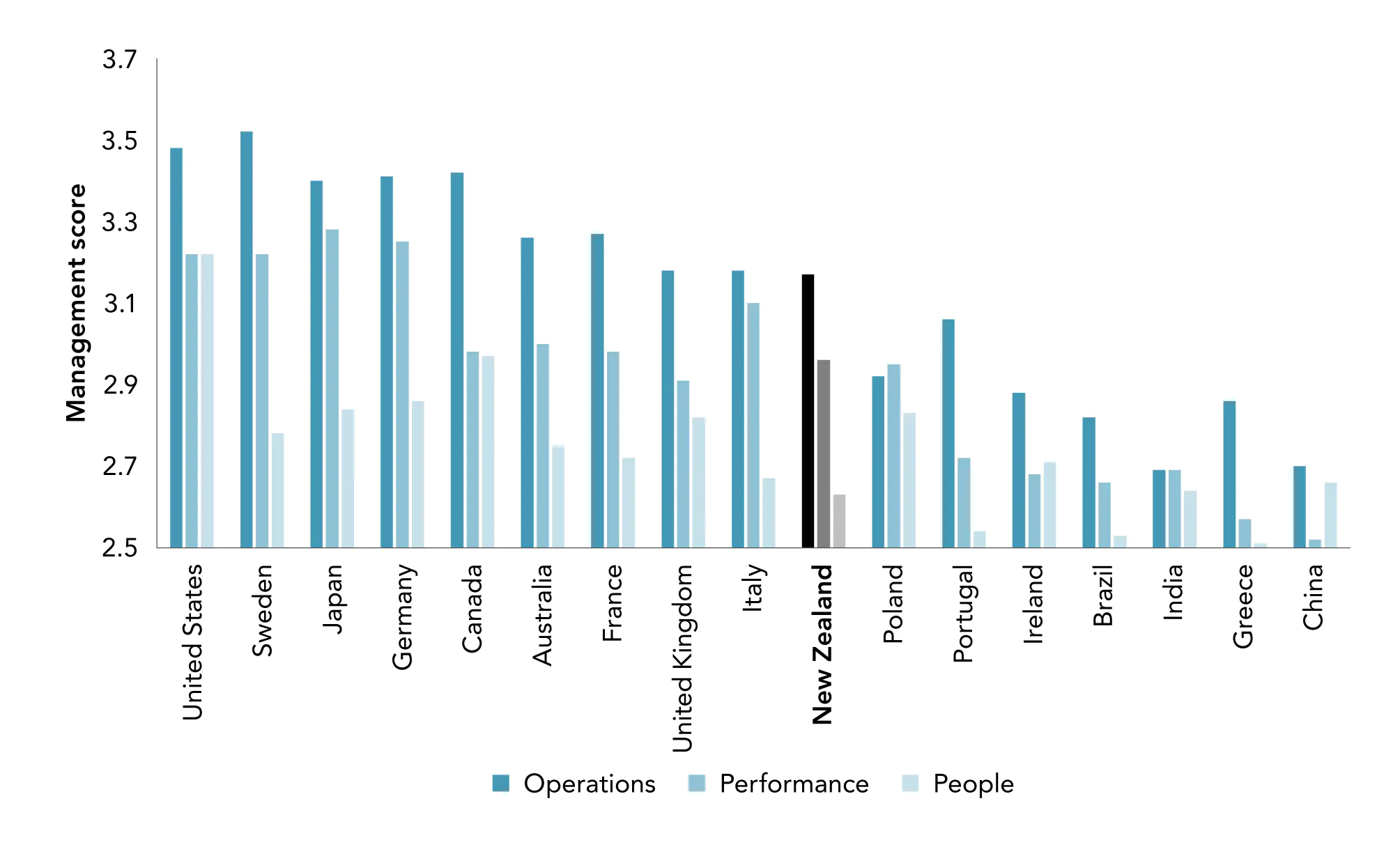

Agarwal, R., Brown, P. J., Bajada, C., Stevens, P., & Green, R. (2020). The effects of competition on management practices in New Zealand–a study of manufacturing firms. International Journal of Production Research, 58(20), 6217–6234.

Aghion, P., & Griffith, R. (2008). Competition and growth: Reconciling theory and evidence. MIT Press.

Ahmad, N., & Koh, S.-H. (2011). Incorporating estimates of household production of non-market services into international comparisons of material well-being. OECD Publishing.

Akcigit, U., & Ates, S. T. (2019). What happened to U.S. business dynamism? (Working Paper No. 25756). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Akcigit, U., & Ates, S. T. (2021). Ten facts on declining business dynamism and lessons from endogenous growth theory. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(1), 257–298.

Allan, C., & Maré, D. C. (2022). Who benefits from firm success? Heterogeneous rent-sharing in New Zealand (Motu Working Paper 22-03). Motu Economic and Public Policy Research.

Andersson, F., Burgess, S., & Lane, J. I. (2007). Cities, matching and the productivity gains of agglomeration. Journal of Urban Economics, 61(1), 112–128.

Andrews, D., & Criscuolo, C. (2019). The best versus the rest: Divergence across firms during the global productivity slowdown (Discussion Paper No. 1645). Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

Australian Productivity Commission & New Zealand Productivity Commission (APC & NZPC). (2019). Growing the digital economy and maximising opportunities for SMEs (Joint Research by the Productivity Commissions of Australia and New Zealand). Productivity Commissions of Australia and New Zealand.

Asian Productivity Organization & OECD. (2021). Towards improved and comparable productivity statistics: A set of recommendations for statistical policy. OECD Publishing.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., Katz, L. F., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2020). The fall of the labor share and the rise of superstar firms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 645–709.

Autor, D. H., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. J. (2003). The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1279–1333.

Barkai, S. (2020). Declining labor and capital shares. The Journal of Finance, 75(5), 2421–2463.

Barrett, P., & Poot, J. (2023). Islands, remoteness and effective policy making: Aotearoa New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 15(3), 682–704.

Bassanini, A., & Caroli, E. (2015). Is work bad for health? The role of constraint versus choice. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 119/120, 13–37.

Battisti, M., Gatto, M. D., & Parmeter, C. F. (2022). Skill-biased technical change and labor market inefficiency. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 139, 104428.

Baumol, W. J. (1993). Health care, education and the cost disease: A looming crisis for public choice. Public Choice, 77(1), 17–28.

Baumol, W. J. (1996). Children of performing arts, the economic dilemma: The climbing costs of health care and education. Journal of Cultural Economics, 20(3), 183–206.

Bedford, R., & Spoonley, P. (2014). Competing for talent: Diffusion of an innovation in New Zealand’s immigration policy. International Migration Review, 48(3), 891–911.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (1998). The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(6), 613–673.

Bertola, G., & Caballero, R. J. (1994). Cross-sectional efficiency and labour hoarding in a matching model of unemployment. The Review of Economic Studies, 61(3), 435–456.

Bertram, G., & Rosenberg, B. (2022, June). How policy and institutions affect the shares of wages, profit, and rent in New Zealand. [Presentation at the Annual Conference of the New Zealand Association of Economists, Wellington].

Birkinshaw, J., Hamel, G., & Mol, M. J. (2008). Management innovation. Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 825–845.

Bloom, N., Jones, C. I., Van Reenen, J., & Webb, M. (2020). Are ideas getting harder to find? American Economic Review, 110(4), 1104–1144.

Bloom, N., Sadun, R., & Reenen, J. V. (2012). Americans do IT better: US multinationals and the productivity miracle. American Economic Review, 102(1), 167–201.

Böckerman, P., & Ilmakunnas, P. (2012). The job satisfaction–productivity nexus: A study using matched survey and register data. ILR Review, 65(2), 244–262.

Bojke, C., Castelli, A., Grašič, K., & Street, A. (2017). Productivity growth in the English national health service from 1998/1999 to 2013/2014. Health Economics, 26(5), 547–565.

Bollyky, T. J., Angelino, O., Wigley, S., & Dieleman, J. L. (2022). Trust made the difference for democracies in COVID-19. The Lancet, 400(10353), 657.

Bolt, J., & Van Zanden, J. L. (2020). Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update (Maddison-Project Working Paper WP-15). University of Groningen.

Boucekkine, R., de la Croix, D., & Licandro, O. (2011). Vintage capital growth theory: Three breakthroughs. In O. de la Grandville (Ed.), Economic growth and development (pp. 87–116). Emerald Group Publishing.

Bowman, J. (2022). Consequences of zombie businesses: Australia’s experience (Working Paper No. 23/2022). Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis, Crawford School of Public Policy.

Brekke, K. A. (1997). Hicksian Income from resource extraction in an open economy. Land Economics, 73(4), 516–527.

Bresnahan, T. F., & Trajtenberg, M. (1995). General purpose technologies ‘Engines of growth’? Journal of Econometrics, 65(1), 83–108.

Bridgman, B., & Greenaway-McGrevy, R. (2018). The fall (and rise) of labour share in New Zealand. New Zealand Economic Papers, 52(2), 109–130.

Brynjolfsson, E., Rock, D., & Syverson, C. (2019). The Productivity J-Curve: How intangibles complement general purpose technologies (MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy Research Brief No. 19/02). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Brynjolfsson, E., Rock, D., & Syverson, C. (2021). The productivity J-Curve: How intangibles complement general purpose technologies. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(1), 333–372.

Card, D., & Lemieux, T. (2001). Can falling supply explain the rising return to college for younger men? A cohort-based analysis. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 705–746.

Carver, T., & Grimes, A. (2016). Income or consumption: Which better predicts subjective wellbeing? (Motu Working Paper 16-12). Motu Economic and Public Policy Research.

Caselli, F., & Coleman, W. J. (2001). Cross-country technology diffusion: The case of computers. American Economic Review, 91(2), 328–335.

Castelli, A., Dawson, D., Gravelle, H., Jacobs, R., Kind, P., Loveridge, P., Martin, S., O’Mahony, M., Stevens, P. A., & Stokes, L. (2007). A new approach to measuring health system output and productivity. National Institute Economic Review, 200, 105–117.

Cerra, V., Lama, R., & Loayza, N. V. (2021). Links between growth, inequality, and poverty (Working Paper No. 2021/068). International Monetary Fund.

Chadeau, A. (1992). What is households’ non-market production worth. OECD Publishing.

Children’s Commissioner. (2018). The Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy (Submission from the Office of the Children’s Commissioner).

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. The Economic Journal, 104(424), 648–659.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

Coe, D. T., & Helpman, E. (1995). International R&D spillovers. European Economic Review, 39(5), 859–887. Coe, D. T., Helpman, E., & Hoffmaister, A. W. (1997). North-south R&D spillovers. The Economic Journal, 107(440), 134–149.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1989). Innovation and learning: The two faces of R&D. The Economic Journal, 99(397), 569–596.

Coleman, A., & Zheng, G. (2020). Job-to-job transitions and the regional job ladder. New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Conway, P., Meehan, L., & Parham, D. (2015). Who benefits from productivity growth? The labour income share in New Zealand (NZPC Working Paper No. 2015/1.

Corrado, C., Haskel, J., Jona-Lasinio, C., & Iommi, M. (2022). Intangible capital and modern economies. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(3), 3–28.

Crawford, R., Fabling, R., Grimes, A., & Bonner, N. (2007). National R&D and patenting: Is New Zealand an outlier? New Zealand Economic Papers, 41(1), 69–90.

Davies, L., Webber, A., & Timmins, J. (2022). The nature of disadvantage. Faced by children in New Zealand: Implications for policy and service provision. Policy Quarterly, 18(3), 38–43.

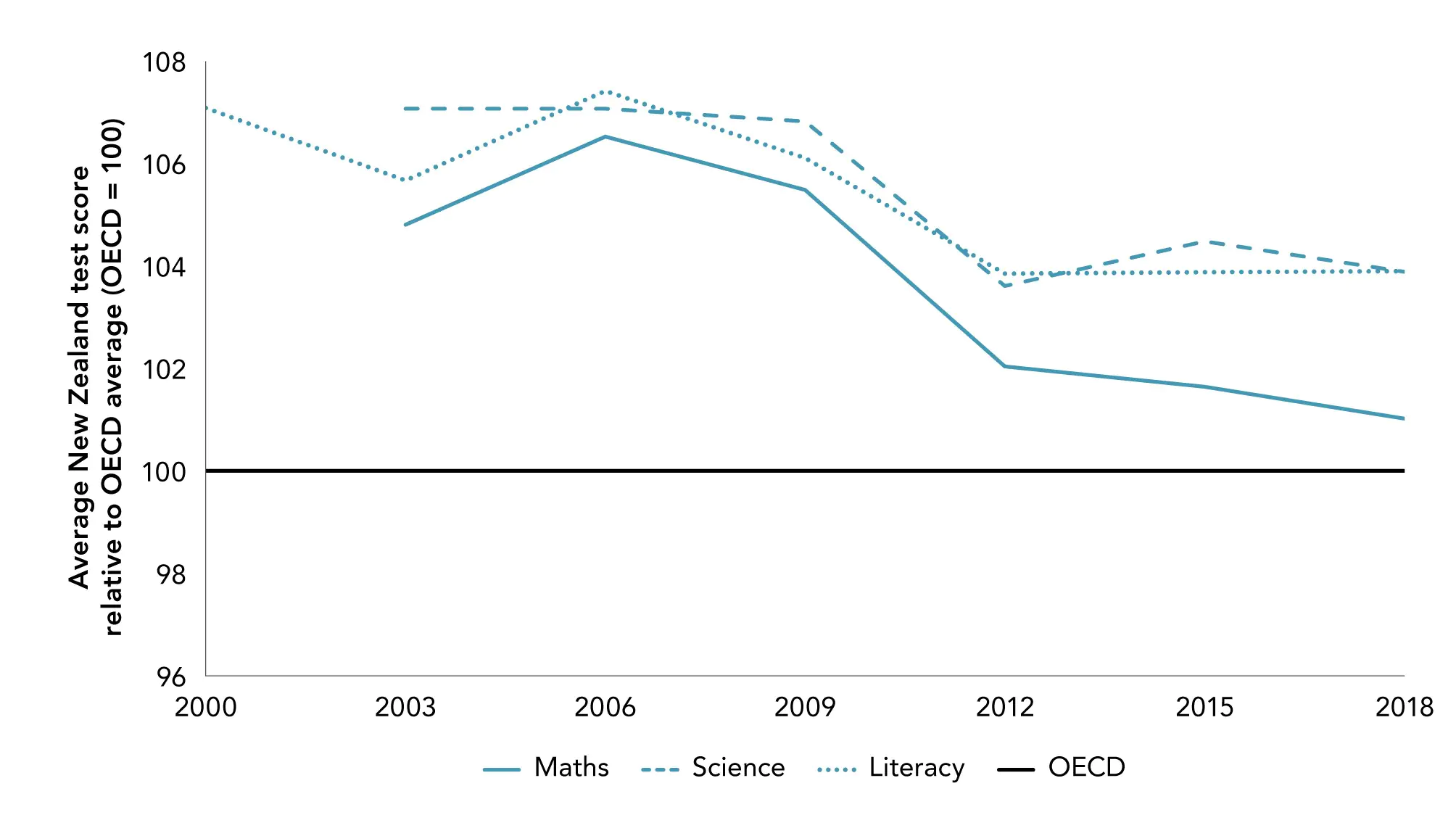

de la Maisonneuve, C., Égert, B., & Turner, D. (2022). Quantifying the macroeconomic impact of COVID-19- related school closures through the human capital channel (No. 1729, OECD Economics Department Working Papers). OECD Publishing.

De Loecker, J., Eeckhout, J., & Unger, G. (2020). The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 561–644.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 53–72.

Diewert, E., & Lawrence, D. (1999). Measuring New Zealand’s productivity (Working Paper No. 99/05). The Treasury.

Dollar, D., Kleineberg, T., & Kraay, A. (2015). Growth, inequality and social welfare: Cross-country evidence. Economic Policy, 30(82), 335–377.

Dollar, D., & Kraay, A. (2002). Growth is good for the poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 7(3), 195–225.

Eaton, J., & Kortum, S. (1999). International technology diffusion: Theory and measurement. International Economic Review, 40(3), 537–570.

Erez, A., & Isen, A. M. (2002). The influence of positive affect on the components of expectancy motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 1055–1067.

Fabling, R. (forthcoming). Working hard or hardly working: Testing for bias in the labour input series. New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Fabling, R., & Grimes, A. (2007). Practice makes profit: Business practices and firm success. Small Business Economics, 29(4), 383–399.

Fabling, R., & Grimes, A. (2010). HR practices and New Zealand firm performance: What matters and who does it? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(4), 488–508.

Fabling, R., & Grimes, A. (2014). The “suite” smell of success: Personnel practices and firm performance. ILR Review, 67(4), 1095–1126.

Fabling, R., & Maré, D. (2012). Cyclical labour market adjustment in New Zealand: The response of firms to the global financial crisis and its implications for workers. (Motu Working Paper 12-04). Motu Economic and Public Policy Research.

Fabling, R., & Sanderson, L. (2013). Exporting and firm performance: Market entry, investment and expansion. Journal of International Economics, 89(2), 422–431.

Fabling, R., & Sanderson, L. (2015). Exchange rate fluctuations and the margins of exports. (Motu Working Paper 15-05). Motu Economic and Public Policy Research.

Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R., & Timmer, M. P. (2015). The next generation of the Penn World Table. American Economic Review, 105(10), 3150–3182.

Fenn, G. W., Liang, N., & Prowse, S. (1997). The private equity market: An overview. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments, 6(4), 1–106.

Fitchett, H., & Jacob, P. (2022). How do we stack up?: The New Zealand housing market in the international context (Analytical Notes AN2022/06). Reserve Bank of New Zealand | Te Pūtea Matua.

Flatau, P., Galea, J., & Petridis, R. (2000). Mental health and wellbeing and unemployment. Australian Economic Review, 33(2), 161–181.

Foliaki, S. (2001). Pacific mental health services and workforce: Moving on the Blueprint. Mental Health Commission.

Fookes, C. (2022). Social Cohesion in New Zealand: Background paper to Te Tai Waiora: Wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand 2022 (Analytical Paper No. 22/01). The Treasury.

Fraser, H. (2018). The labour income share in New Zealand: An update (Research Note No. 2018/1). New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Gemmell, N., Nolan, P., & Scobie, G. (2017). Public sector productivity: Quality adjusting sector-level data on New Zealand schools (Working Paper No. 2017/2). New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Gemmell, N., Nolan, P., & Scobie, G. (2018). Quality adjusting education sector productivity. Policy Quarterly, 14(3), 46–51.

Gluckman, P., Bardsley, A., Spoonley, P., Royal, C., Simon-Kumar, N., & Chen, A. (2021). Sustaining Aotearoa New Zealand as a cohesive society. Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures.

Gordon, R. J. (2018). Why has economic growth slowed when innovation appears to be accelerating? (Working Paper No. 24554). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Graunt, J. (1676). Natural and political observations made upon the bills of mortality. John Martyn.

Green, R., & Agarwal, R. (2011). Management matters in New Zealand: How does manufacturing measure up? Ministry of Economic Development New Zealand.

Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2007). Firm heterogeneity, exporting and foreign direct investment. The Economic Journal, 117(517), F134–F161.

Greenwood, J., & Jovanovic, B. (1990). Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 1), 1076–1107.

Griffith, R., Redding, S., & Reenen, J. V. (2004). Mapping the two faces of R&D: Productivity growth in a panel of OECD industries. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(4), 883–895.

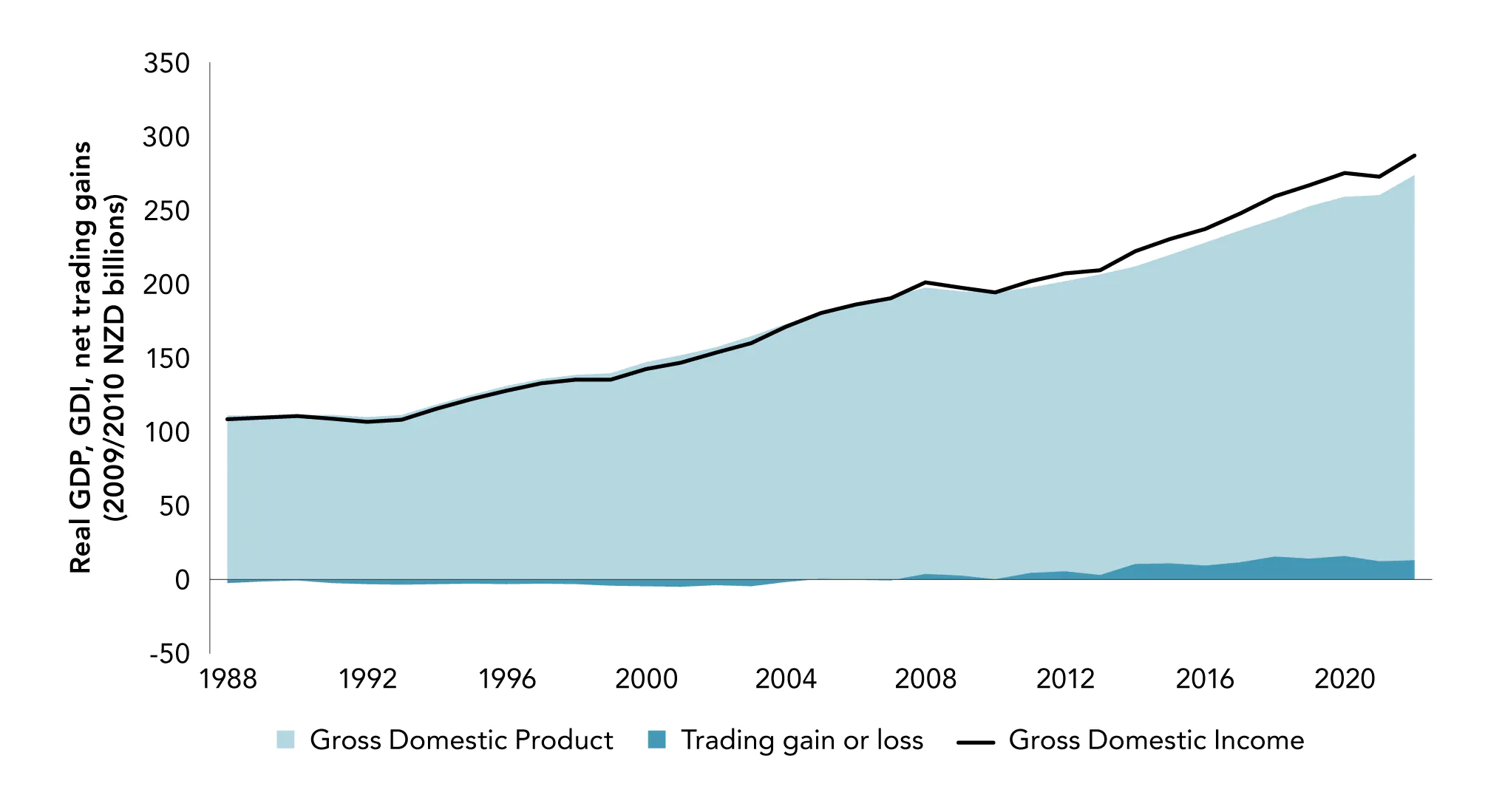

Grimes, A., & Wu, S. (2022). Sustainable consumption growth: New Zealand’s surprising performance. New Zealand Economic Papers, (2022, October 26), 1–15.

Gromada, A., Rees, G., & Chzhen, Y. (2020). Worlds of influence: Understanding what shapes child well-being in rich countries (Innocenti Report Card 16). UNICEF.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1990). Trade, innovation, and growth. The American Economic Review, 80(2), 86–91.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Quality ladders in the theory of growth. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(1), 43–61.

Grossman, G. M., & Oberfield, E. (2022). The elusive explanation for the declining labor share. Annual Review of Economics, 14(1), 93–124.

Hall, B. H., & Khan, B. (2003). Adoption of new technology. National Bureau of Economic Research. Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2020). The economic impacts of learning losses. OECD Publishing.

Hanushek, E., & Woessmann, L. (2010). The high cost of low educational performance: The long-run economic impact of improving PISA outcomes. OECD.

Hartmann, D., Guevara, M. R., Jara-Figueroa, C., Aristarán, M., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2017). Linking economic complexity, institutions, and income inequality. World Development, 93, 75–93.

Hausmann, R., Hidalgo, C. A., Bustos, S., Coscia, M., & Simoes, A. (2014). The atlas of economic complexity: Mapping paths to prosperity. MIT Press.

Hausmann, R., Hwang, J., & Rodrik, D. (2007). What you export matters. Journal of Economic Growth, 12, 1–25.

Hellmann, T., & Puri, M. (2000). The interaction between product market and financing strategy: The role of venture capital. The Review of Financial Studies, 13(4), 959–984.

Helpman, E. (1984). A simple theory of international trade with multinational corporations. Journal of Political Economy, 92(3), 451–471.

Helpman, E., & Krugman, P. R. (1987). Market structure and foreign trade: Increasing return, imperfect competition, and the international economy (Reprint edition). MIT Press.

Hicks, J. R. (1946). Value and capital. Oxford University Press.

Hidalgo, C. (2015). Why information grows: The evolution of order, from atoms to economies. Basic Books.

Hidalgo, C. A., Klinger, B., Barabási, A.-L., & Hausmann, R. (2007). The product space conditions the development of nations. Science, 317(5837), 482–487.

Horstmann, I. J., & Markusen, J. R. (1987). Strategic investments and the development of multinationals. International Economic Review, 28(1), 109–121.

Horstmann, I. J., & Markusen, J. R. (1992). Endogenous market structures in international trade (natura facit saltum). Journal of International Economics, 32(1–2), 109–129.

Howitt, P. (2010). Endogenous growth theory. In S. N. Durlaug & L. E. Bloom (Eds.), Economic growth. The New Palgrave economics collection (pp. 68–73). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hoynes, H., Miller, D. L., & Schaller, J. (2012). Who suffers during recessions? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 27–48.

Hughes, T., Cardona, D., & Armstrong, C. (2022). Trends in wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand: 2000–2020 [Background Paper for the 2022 Wellbeing Report]. The Treasury.

Hulten, C. R. (2007). Total factor productivity: A short biography. In C. R. Hulten, E. R. Dean, & M. Harper (Eds.), New developments in productivity analysis (pp. 1–54). University of Chicago Press.

Ifcher, J., & Zarghamee, H. (2011). Happiness and time preference: The effect of positive affect in a random- assignment experiment. American Economic Review, 101(7), 3109–3129.

Inklaar, R., Woltjer, P., Albarrán, D. G., & Gallardo, D. (2019). The composition of capital and cross-country productivity comparisons. International Productivity Monitor, 36, 34–52.

Isen, A. M. (2008). Some ways in which positive affect influences decision making and problem solving. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd Edition) (pp. 548–573). The Guilford Press.

Isen, A. M., & Geva, N. (1987). The influence of positive affect on acceptable level of risk: The person with a large canoe has a large worry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39(2), 145–154.

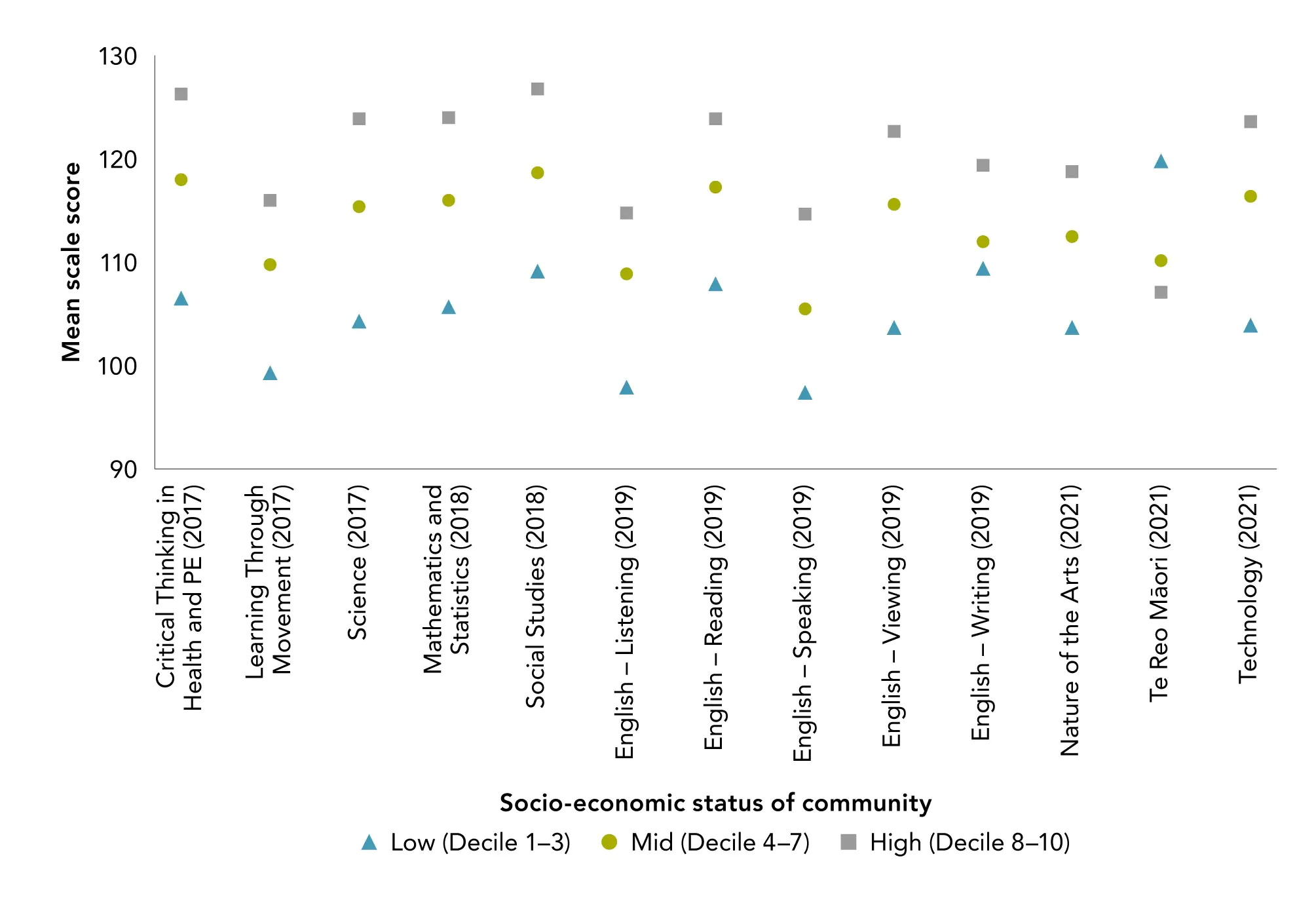

Jagger, D., & Stevens, P. (2019). He Whakaaro: Accounting for educational disadvantage [He Whakaaro Education Insights]. Ministry of Education.

Janssen, J., Galt, M., & Bollinger, G. (2022). New Zealand’s productivity performance: Taking a broader view (Analytical Note No. 22/05). The Treasury.

Johansen, L. (1959). Substitution versus fixed production coefficients in the theory of economic growth: A synthesis. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 27(2), 157–176.

Johnson, A. (2023, March 30). Which jobs will AI replace? These 4 industries will be heavily impacted. Forbes. Karabarbounis, L., & Neiman, B. (2014). The global decline of the labor share. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), 61–103.

Karabarbounis, L., & Neiman, B. (2019). Accounting for factorless income. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 33, 167–228.

Keller, W. (2002). Geographic localization of international technology diffusion. American Economic Review, 92(1), 120–142.

Keller, W. (2004). International technology diffusion. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(3), 752–782. Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Macmillan & Co.

Kirchsteiger, G., Rigotti, L., & Rustichini, A. (2006). Your morals might be your moods. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 59(2), 155–172.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288.

Kneller, R., & Stevens, P. A. (2006). Frontier technology and absorptive capacity: Evidence from OECD manufacturing industries. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 68(1), 1–21.

Kuznets, S. (1934). National income, 1929-1932. In S. Kuznets, National income, 1929-1932 (pp. 1–12). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lattimore, R. G., & Hawke, G. (1999). Visionaries, farmers and markets: An economic history of New Zealand agriculture (No. 12830). AgEcon Search.

Layard, P., & Layard, R. (2011). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. Penguin UK.

Layard, R. (2006). Happiness and public policy: A challenge to the profession. The Economic Journal, 116(510), C24–C33.

Le, T., & Jaffe, A. B. (2017). The impact of R&D subsidy on innovation: Evidence from New Zealand firms. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 26(5), 429–452.

Lepenies, P., & Gaines, J. (2016). The power of a single number: A political history of GDP. Columbia University Press.

Levine, R. (2005). Finance and growth: Theory and evidence. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1(A), 865–934.

Levine, R., & Zervos, S. (1998). Stock markets, banks, and economic growth. The American Economic Review, 88(3), 537–558.

Liu, B., Chen, H., & Gan, X. (2019). How much is too much? The influence of work hours on social development: An empirical analysis for OECD countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4914.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.

Lucas, R. E., Jr. (2015). Human capital and growth. American Economic Review, 105(5), 85–88.

Maré, D. C., & Graham, D. J. (2013). Agglomeration elasticities and firm heterogeneity. Journal of Urban Economics, 75, 44–56.

Maré, D. C., Hyslop, D. R., & Fabling, R. (2017). Firm productivity growth and skill. New Zealand Economic Papers, 51(3), 302-326.

Maré, D. C., Le, T., Fabling, R., & Chappell, N. (2017). Productivity and the allocation of skills (Motu Working Paper 17-04). Motu Economic and Public Policy Research.

Maré, D. C., Morton, M., & Sanderson, L. (forthcoming). Missing migrants: Border closures as a labour supply shock. Motu Economic and Public Policy Research.

Markusen, J. R. (1984). Multinationals, multi-plant economies, and the gains from trade. Journal of International Economics, 16(3–4), 205–226.

Markusen, J. R., & Venables, A. J. (1998). Multinational firms and the new trade theory. Journal of International Economics, 46(2), 183–203.

Markusen, J. R., & Venables, A. J. (2000). The theory of endowment, intra-industry and multi-national trade. Journal of International Economics, 52(2), 209–234.

Mason, G., & Osborne, M. (2007). Productivity, capital-intensity and labour quality at sector level in New Zealand and the UK (Working Paper No. 07/01). The Treasury.

McCann, P. (2009). Economic geography, globalisation and New Zealand’s productivity paradox. New Zealand Economic Papers, 43(3), 279–314.

McGowan, M. A., Andrews, D., & Millot, V. (2017). The walking dead?: Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries (Working Paper No. 1372). OECD.

McNaughton, T. (2008). Adjusting for changes in labour composition in Statistics New Zealand’s Productivity Series. Labour, Employment and Work in New Zealand (2008), 420–423.

Mincer, J. (1984). Human capital and economic growth. Economics of Education Review, 3(3), 195–205.

Morris, M., & Stevens, P. (2010). Evaluation of a New Zealand business support programme using firm performance micro-data. Small Enterprise Research, 17(1), 30–42.

Moughan, P. J. (20 1). Floreat Scientia: Celebrating New Zealand’s agrifood innovation (1st Edition). Wairau Press.

Myers, M. (2009). The impact of the economic downturn on productivity growth. Economic & Labour Market Review, 3, 18–25.

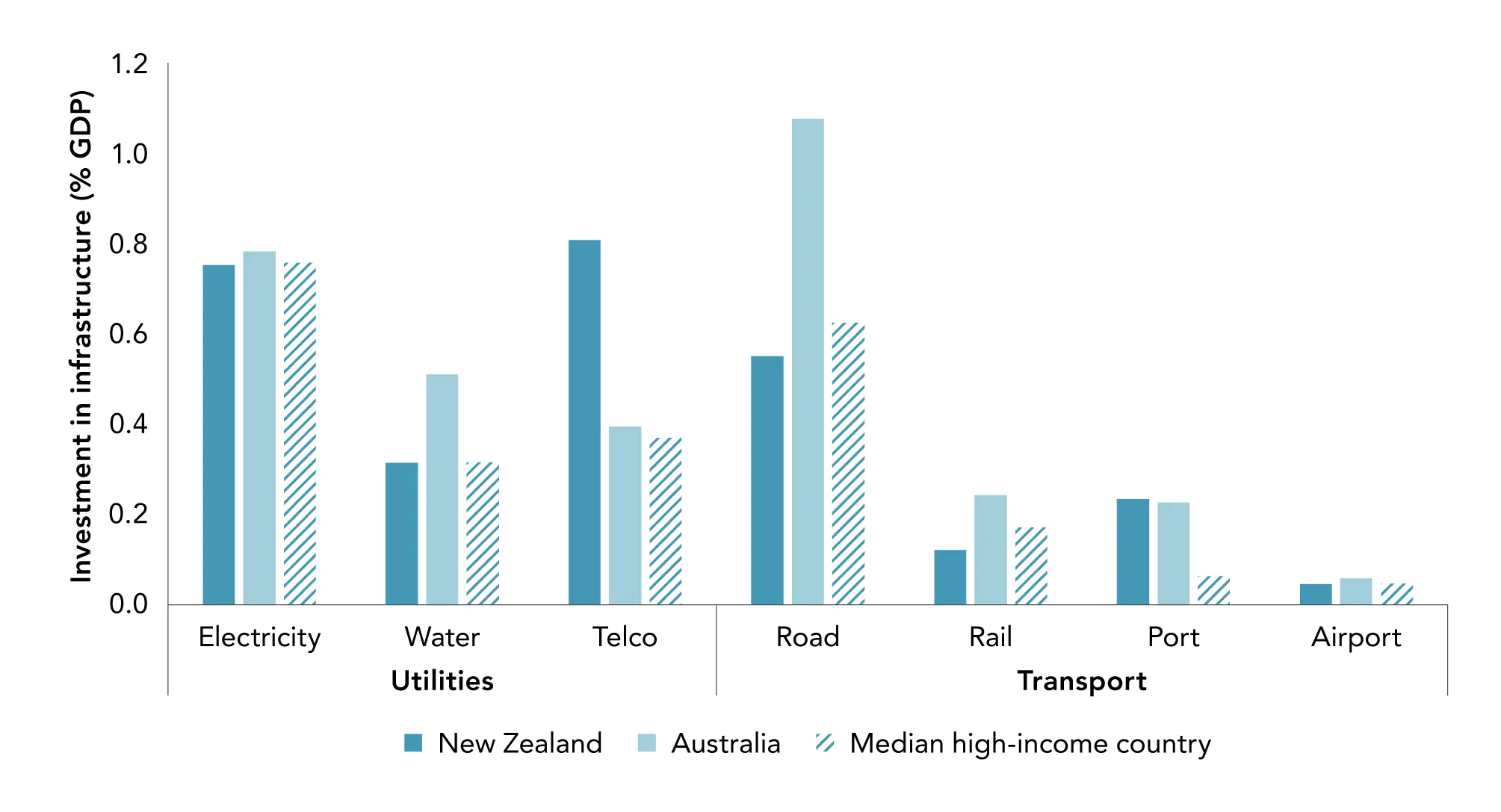

New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2021). Investment gap or efficiency gap? Benchmarking New Zealand’s investment in infrastructure (Te Waihanga Research Insights Series).

New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2022a). The decline of housing supply in New Zealand: Why it happened and how to reverse it. (Te Waihanga Research Insights Series.).

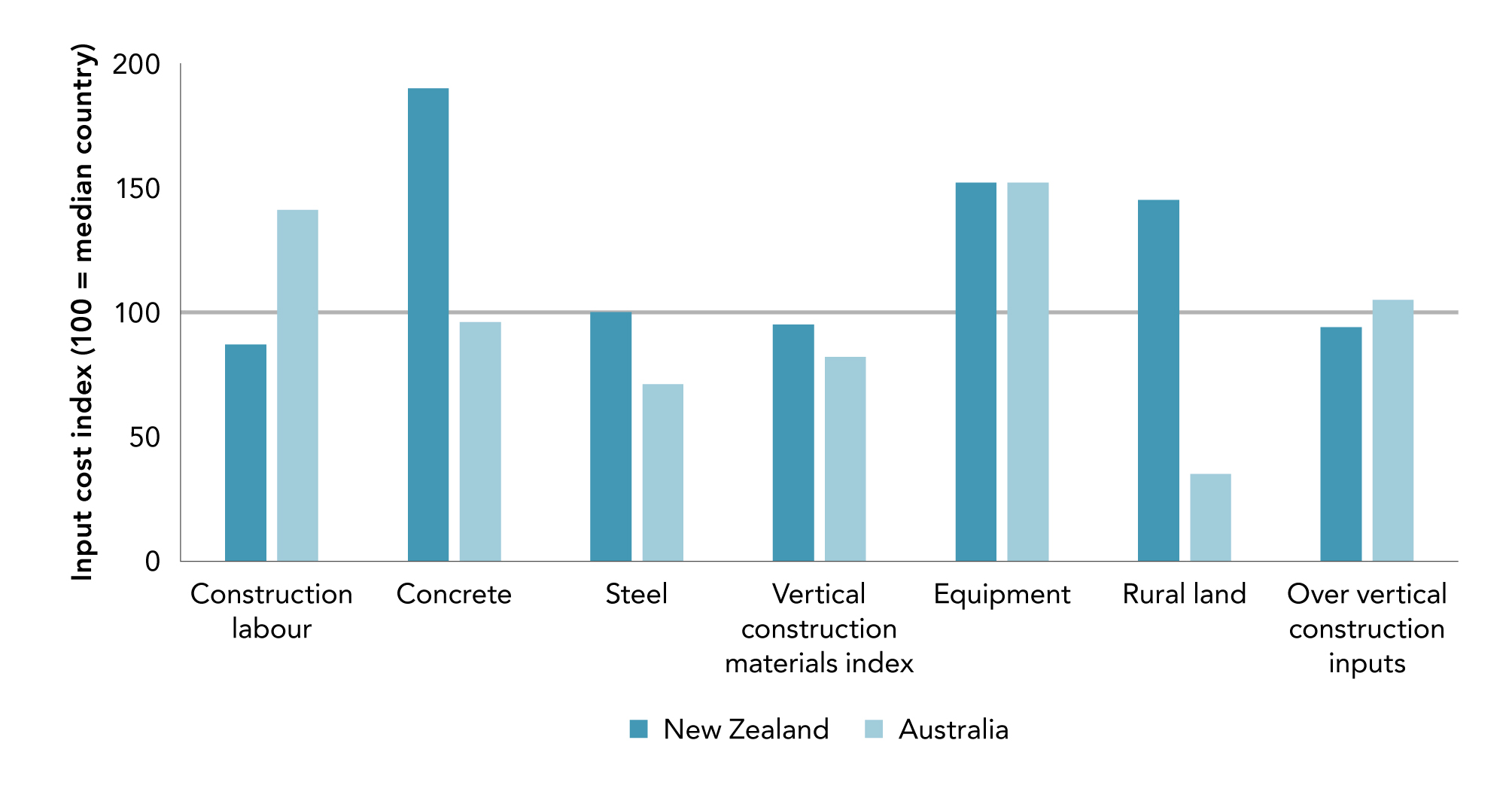

New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2022b). The lay of the land: Benchmarking New Zealand’s infrastructure delivery costs (Te Waihanga Research Insights Series).

Nordhaus, W. D., & Tobin, J. (1973). Is growth obsolete? In M. Moss (Ed.), The measurement of economic and social performance (pp. 509–564). National Bureau of Economic Research.

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112. Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities. Harvard University Press.

Nussbaum, M. C., & Sen, A. (Eds.). (1993). The quality of life. Clarendon Press Oxford.

New Zealand Productivity Commission (NZPC). (2018a). Improving state sector productivity [Final Report]. NZPC. (2018b). Low-emissions economy [Final report].

NZPC. (2019). Technological change and the future of work [Issues paper]. NZPC. (2020a). New Zealand firms: Reaching for the frontier [Draft report].

NZPC. (2020b). Technological change and the future of work [Final Report]. NZPC. (2021a). New Zealand Firms: Reaching for the frontier [Final Report]. NZPC. (2021b). Productivity by the numbers.

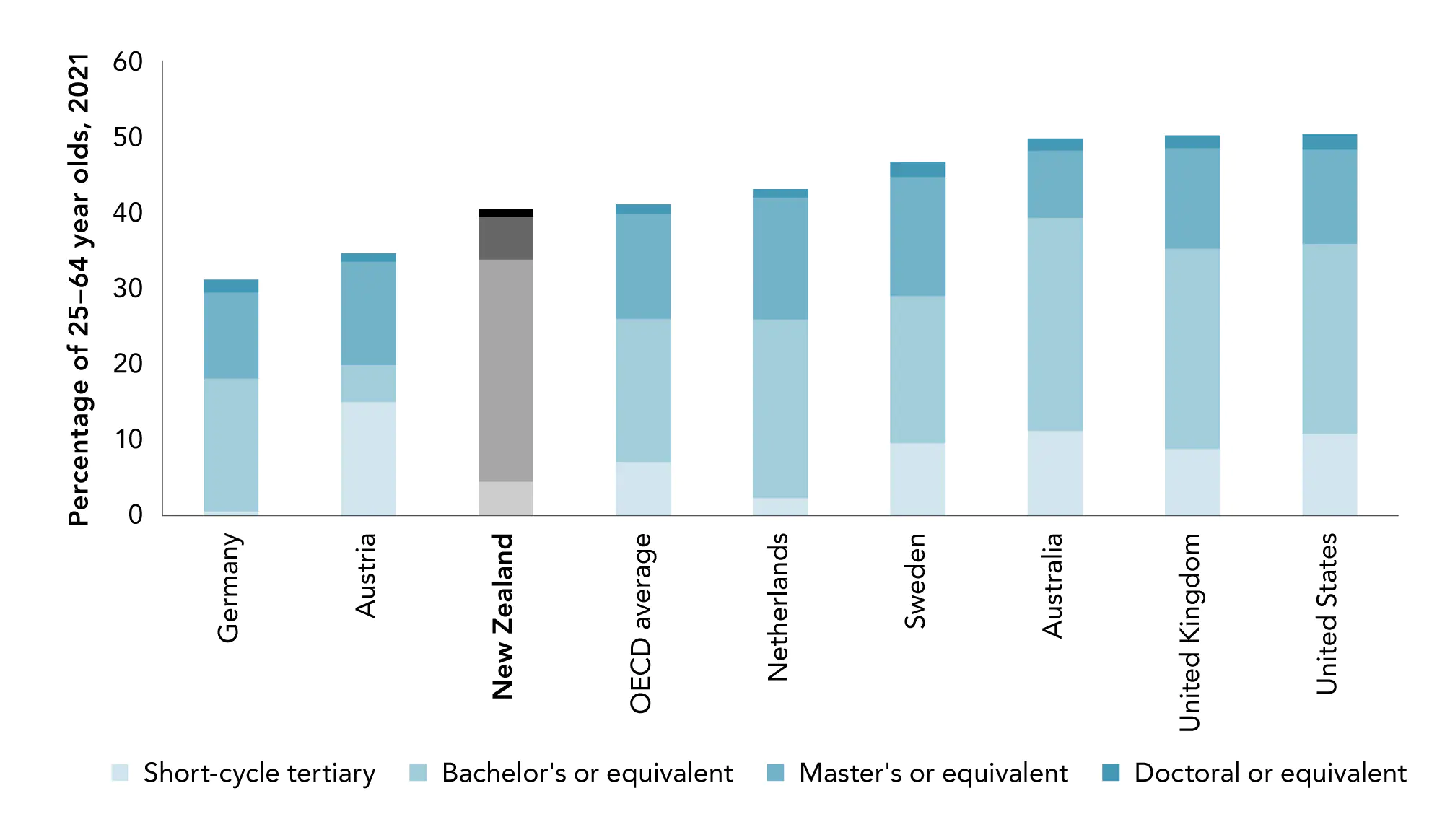

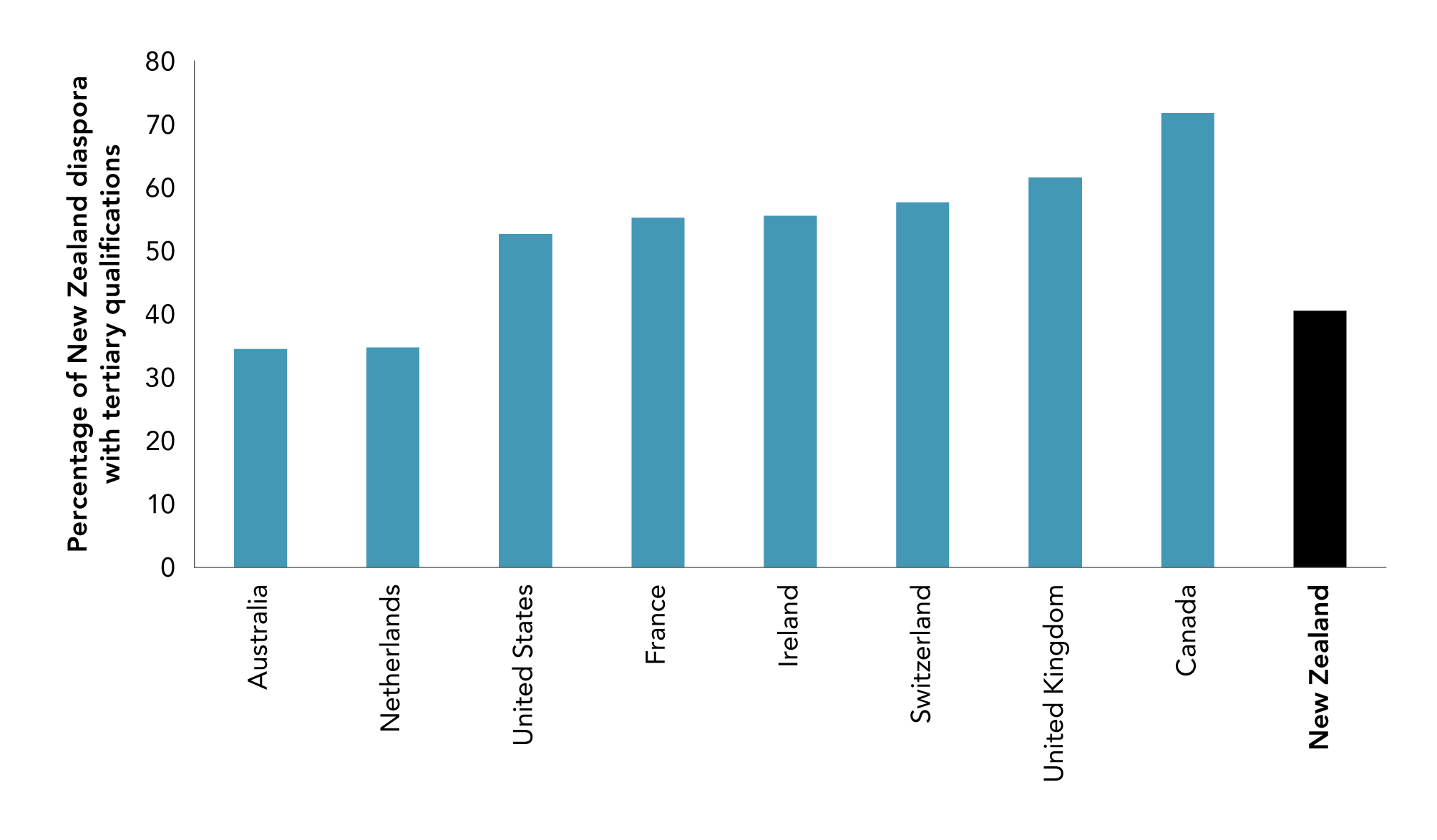

NZPC. (2022a). Immigration by the numbers.

NZPC. (2022b). Immigration — Fit for the future [Final Report]. NZPC. (2023a). A fair chance for all [Final report].

NZPC. (2023b). Frontier Firms: Follow-on review [Final Report].

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). The future of productivity. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2017a). International trade, foreign direct investment and global value chains [New Zealand Trade and Investment Statistical Note]. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2017b). OECD Economic Surveys: New Zealand 2017.

OECD. (2017c). OECD science, technology and industry scoreboard 2017: The digital transformation. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2018). Equity in education: Breaking down barriers to social mobility. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2022a). Identifying the main drivers of productivity growth: A literature review. OECD Publishing. OECD. (2022b). OECD Economic Surveys: New Zealand 2022 [Overview].

Oi, W. Y. (1962). Labor as a quasi-fixed factor. Journal of Political Economy, 70(6), 538–555.

O’Mahony, M., & Stevens, P. (2006). International comparisons of output and productivity in public service provision: A review. In G. A. Boyne, K. J. Meier, L. J. O’Toole Jr., & R. M. Walker (Eds.), Public service performance: Perspectives on measurement and management (pp. 233–253). Cambridge University Press.

Oswald, A. J., Proto, E., & Sgroi, D. (2015). Happiness and productivity. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(4), 789–822.

Parente, S. L., & Prescott, E. C. (1994). Barriers to technology adoption and development. Journal of Political Economy, 102(2), 298–321.

Partridge, R., & Wilkinson, B. (2019). Work in progress: Why Fair Pay Agreements would be bad for labour. The New Zealand Initiative.

Pearce, D. W., & Atkinson, G. (1995). Measuring sustainable development. In D. Bromley (Ed.), The handbook of environmental economics (pp. 166–181). Blackwell.

Pells, S. (2018). How useful are our productivity measures? Literature review. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

Pelosi, M., Rodano, G., & Sette, E. (2021). Zombie firms and the take-up of support measures during Covid-19 (Occasional Papers No. 650). Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area.

Pencavel, J. (2015). The productivity of working hours. The Economic Journal, 125(589), 2052–2076. Piketty, T. (2018). Capital in the twenty-first century. Harvard University Press.

Prescott, E. C. (1998). Lawrence R. Klein lecture 1997: Needed: A theory of total factor productivity. International Economic Review, 39(3), 525–551.

Reddell, M. (2017, August 29). Labour share of income. Croaking Cassandra.

Riekhoff, A.-J., Krutova, O., & Nätti, J. (2019). Working-hour trends in the Nordic countries: Convergence or divergence? Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 9(3), 45-70.

Riggs, L. (Forthcoming). Multi-dimensional disadvantage and wellbeing [Working Paper]. New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Riggs, L., Keall, M., Howden-Chapman, P., & Baker, M. G. (2021). Environmental burden of disease from unsafe and substandard housing, New Zealand, 2010–2017. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99(4), 259–270.

Robbins, C. A. (2016). Using new growth theory to sharpen the focus on people and places in innovation measurement. Blue Sky Forum, Informing science innovation policies, towards the next generation of data and indicators.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 2), S71–S102.

Rosenberg, B. (2017). A brief history of labour’s share of income in New Zealand 1939–2016. In G. Anderson, A. Geare, E. Rasmussen, & M. Wilson (Eds.), Transforming workplace relations in New Zealand 1976-–016 (pp. 79–106). Victoria University Press.

Rosenberg, N. (1972). Factors affecting the diffusion of technology. Explorations in Economic History, 10(1), 3–33.

Sanderson, L. (2022). The evolution of management practices in New Zealand (Chief Economist Unit Working Paper No. 22/03). Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

Schneider, T., Hong, G. H., & Van Le, A. (2018). Japan: Land of the rising robots. Finance & Development, 55(002), 28–21.

Schreyer, P., & Pilat, D. (2001). Measuring productivity. OECD Economic Studies, 33(2), 127–170. Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. Harper & Brothers.

Scott, D. (2020). Education and earnings: A New Zealand update. Ministry of Education.

Scur, D., Sadun, R., Van Reenen, J., Lemos, R., & Bloom, N. (2021). The World Management Survey at 18: Lessons and the way forward. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 37(2), 231–258.

Sen, A. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. North-Holland.

Sen, A. (2003). Development as capability expansion. In S. Fukuda-Parr & A. Shiva Kumar (Eds.), Human development (pp. 3–16). Oxford University Press.

Simpson, H. (2009). Productivity in public services. Journal of Economic Surveys, 23(2), 250–276.

Sin, I., Fabling, R., Jaffe, A. B., Maré, D. C., & Sanderson, L. (2014). Exporting, innovation and the role of immigrants (Motu Working Paper 14-15). Motu Economic and Public Policy Research.

Solow, R. M. (2000). Notes on social capital and economic performance. In P. Dasgupta & I. Serageldin (Eds.), Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective (pp. 6–10). World Bank.

Stansbury, A., & Summers, L. (2020). The declining worker power hypothesis: An explanation for the recent evolution of the American economy [NBER Working Paper No. 27193]. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Stats NZ. (2020, September 7). Four in 10 employed New Zealanders work from home during lockdown [Media Release].

Stats NZ. (2022, October 27). New Zealand business demography statistics: At February 2022 [Information release].

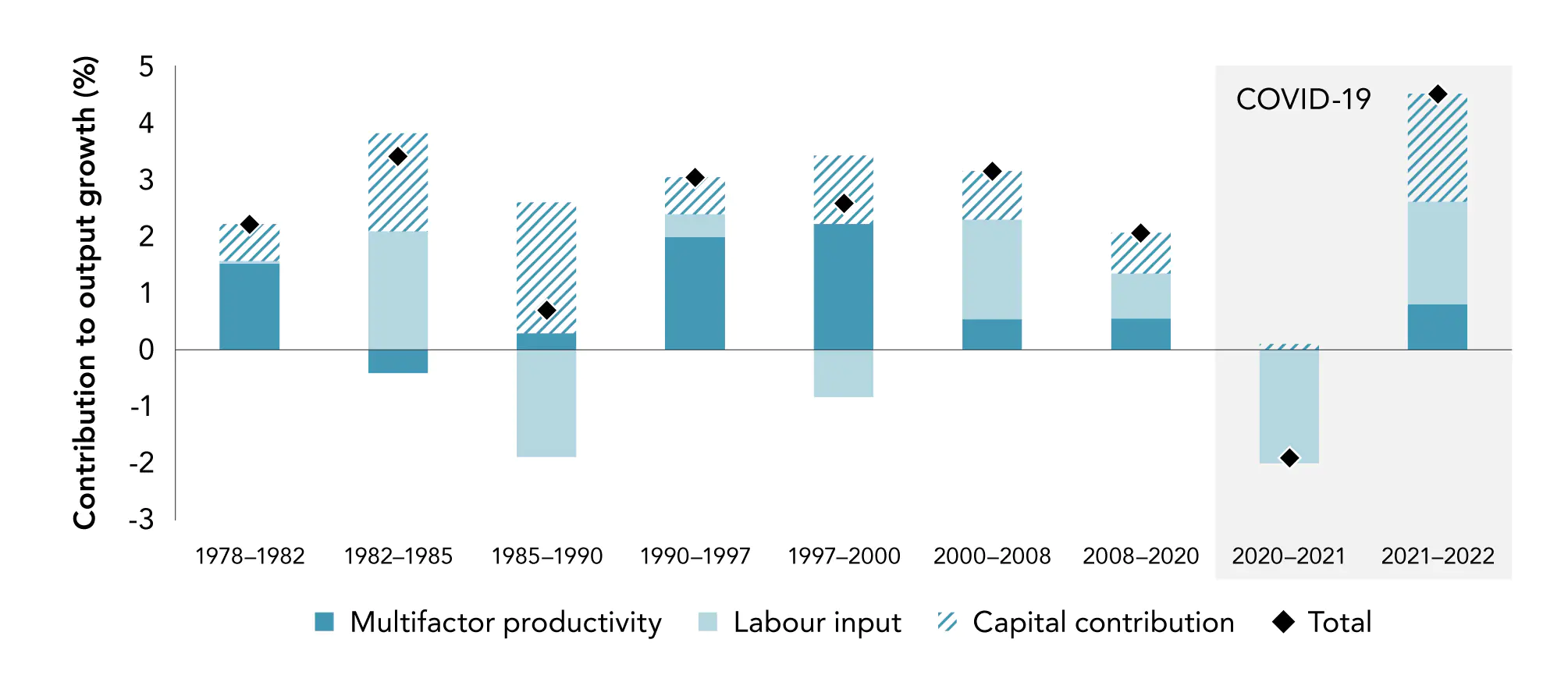

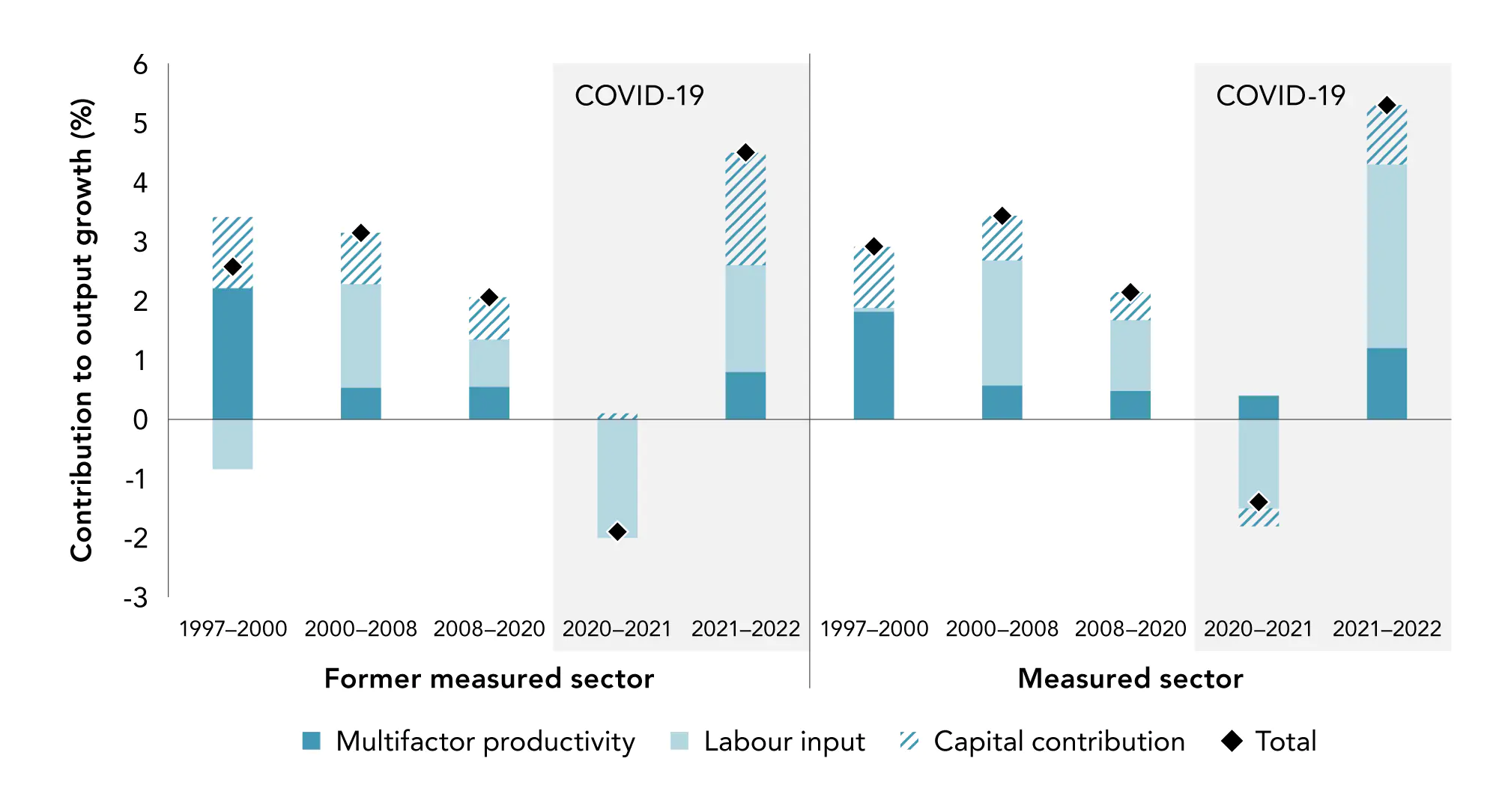

Stats NZ. (2023, March). Productivity statistics: 1978–2022.

Stevens, P. (2006). Public sector performance: Introduction. National Institute Economic Review, 197, 65–66.

Stevens, P. (2007). Skill shortages and firms’ employment behaviour. Labour Economics, 14(2), 231–249.

Stevens, P. (2011). Innovation and the modern economy: An economist’s perspective. In Moughan, P. J., McCool, P., & Riddet Institute (Eds.), Floreat Scientia: Celebrating New Zealand’s agrifood innovation (pp. 17–22). Wairau Press.

Stevens, P., Stokes, L., & O’Mahony, M. (2006). Metrics, targets and performance. National Institute Economic Review, 197, 80–92.

Studenski, P. (1958). The income of nations: Theory, measurement, and analysis: Past and present; A study in applied economics and statistics (Vol. 1). New York University Press.

Summers, L. (2016). Secular stagnation and monetary policy. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 98(2), 93–110.

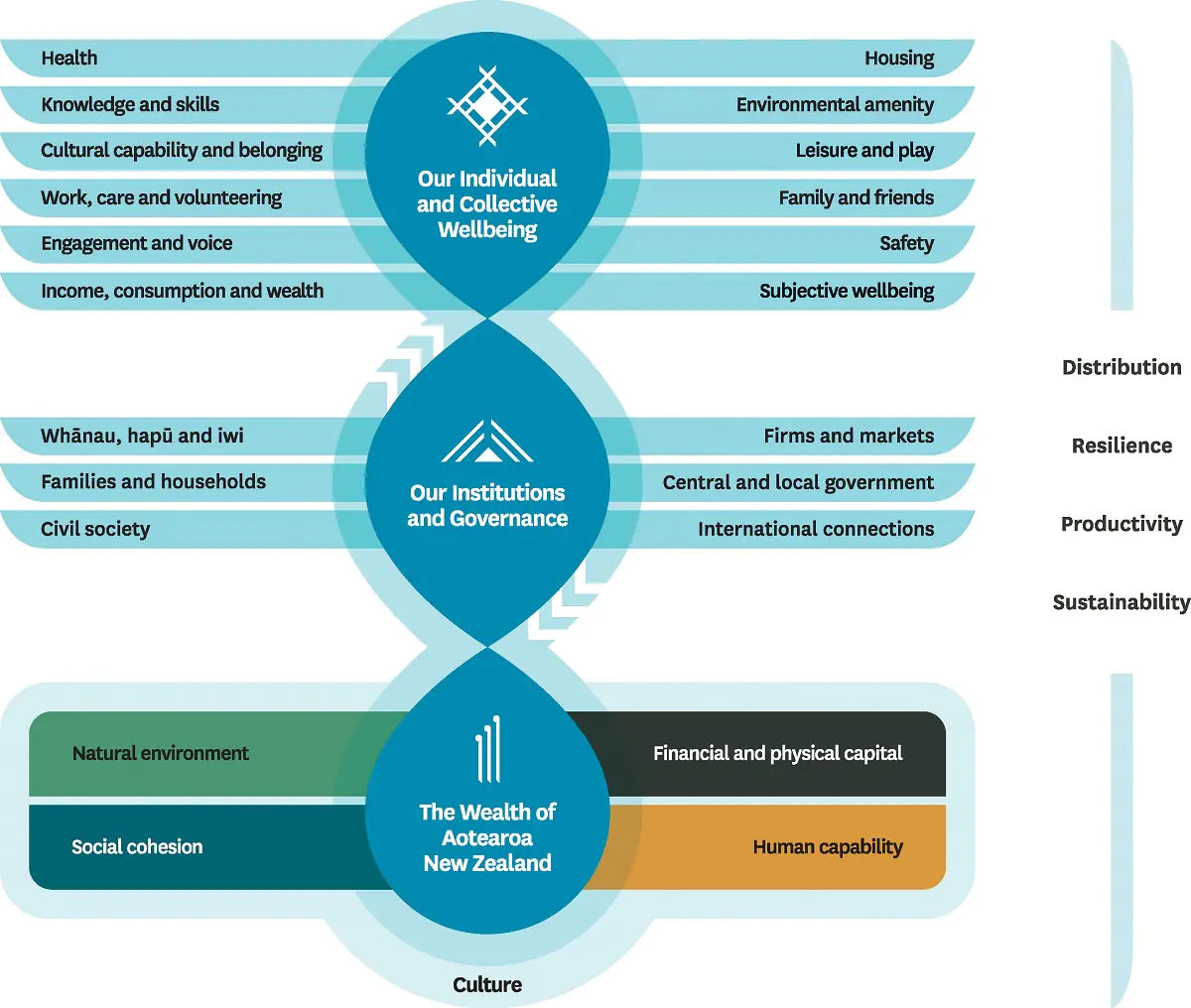

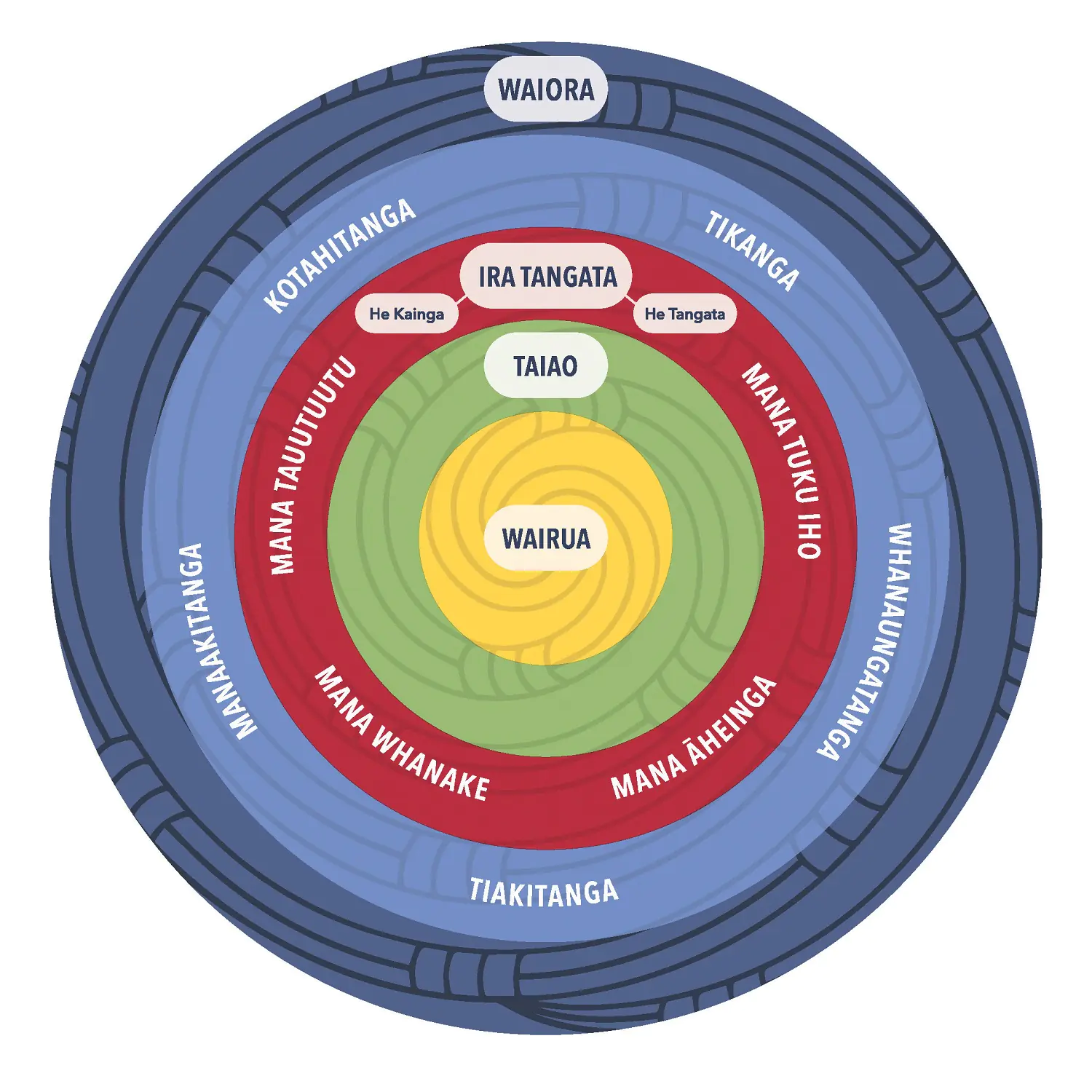

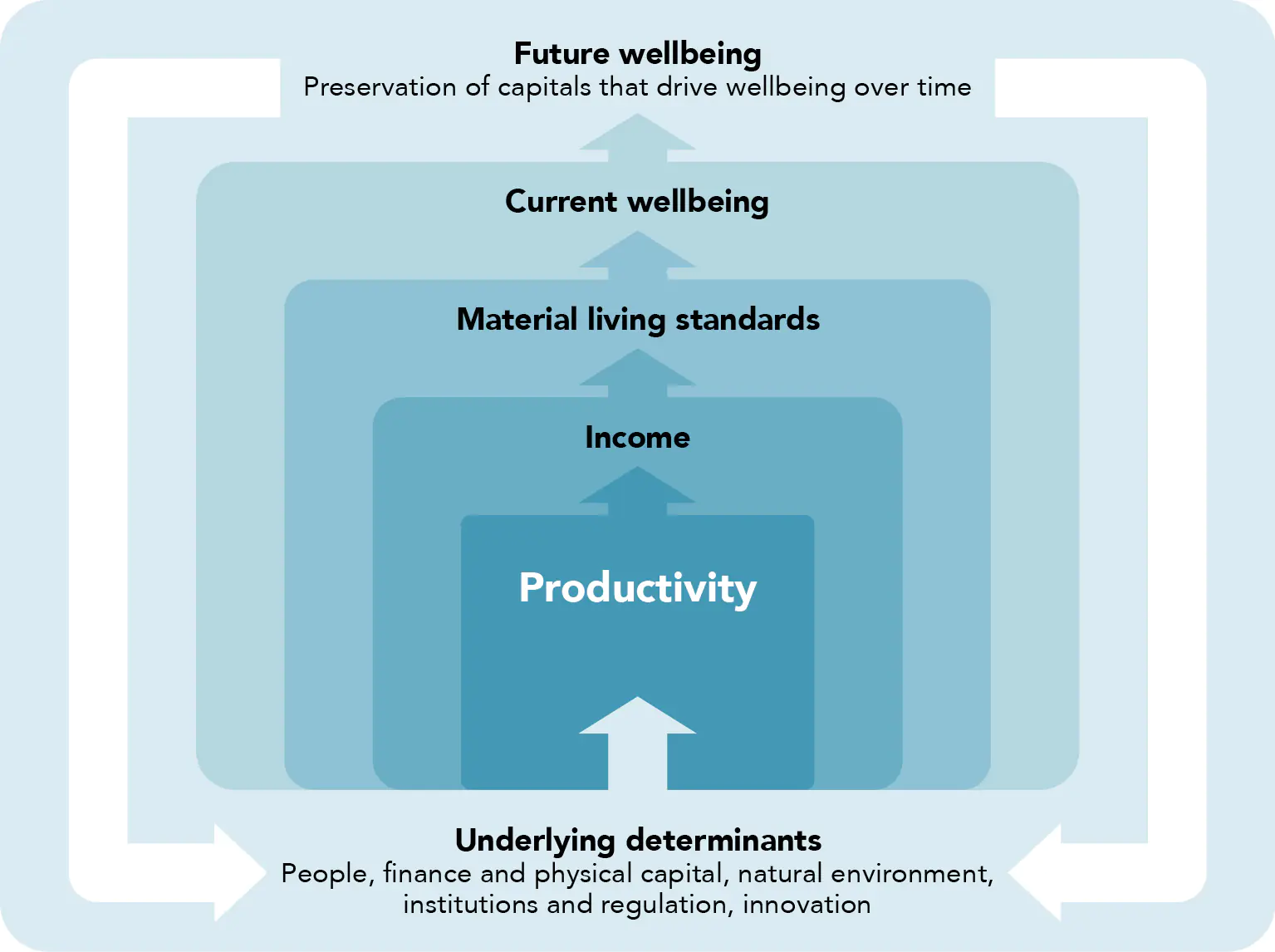

The Treasury. (2021). The Living Standards Framework 2021.

The Treasury. (2022). Te Tai Waiora: Wellbeing in Aotearoa New Zealand 2022.

Tipper, A. (2013). Output and productivity in the education and health industries. [Paper presented at the 54th New Zealand Association of Economists Conference, Wellington, New Zealand]. Stats NZ.

Triplett, J. E. (2001). What’s different about health? Human repair and car repair in national accounts and in national health accounts. In D. M. Cutler & E. R. Berndt (Eds.) Medical care output and productivity (pp. 15–96). University of Chicago Press.

Ward, A., Zinni, M. B., & Marianna, P. (2018). International productivity gaps: Are labour input measures comparable? (Working Paper No. 99; p. OECD). OECD Publishing.

Waring, M. (2018). Still counting: Wellbeing, women’s work and policy-making. Bridget Williams Books. Waring, M., & Steinem, G. (1988). If women counted: A new feminist economics. Harper & Row.

Wiki, J., Marek, L., Hobbs, M., Kingham, S., & Campbell, M. (2021). Understanding vulnerability to COVID-19 in New Zealand: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 51(sup1), S179–S196.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Evidence from panel data. Economica, 65(257), 1–15.

World Bank. (20 1). The changing wealth of nations: Measuring sustainable development in the new millennium. Xu, B. (2000). Multinational enterprises, technology diffusion, and host country productivity growth. Journal of Development Economics, 62(2), 477–493.

Yeung, J. W., Zhang, Z., & Kim, T. Y. (2018). Volunteering and health benefits in general adults: Cumulative effects and forms. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–8.