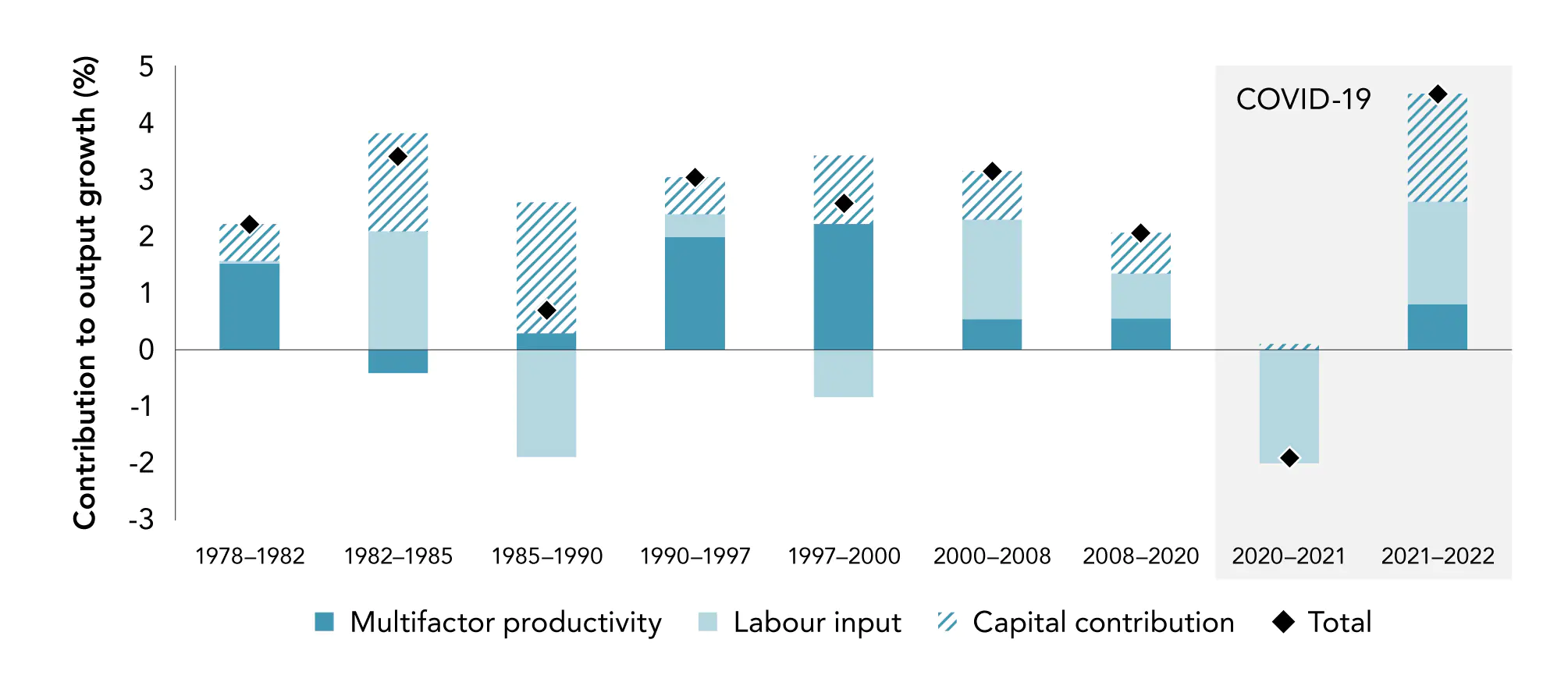

In this section, we examine what has changed since the previous Productivity by the numbers (NZPC, 2021b). The analysis presented in this section is based on the most recent release of Stats NZ’s productivity statistics from 1978–2022 (Stats NZ, 2023).

Although the latest figures understandably are of most interest, it is important to state that annual movements can be volatile and often do not reflect changes in the underlying drivers of productivity. Further, each new release of productivity statistics comes with revised historical data for both input and output indicators, resulting in updated productivity estimates for previous years.

Measured productivity varies over the economic cycle for both economic and measurement reasons, so economists generally focus on the longer-term patterns, and Stats NZ recommends focusing on productivity across growth cycles. Averaging over the whole economic cycle provides the best opportunity to understand the underlying position of productivity in Aotearoa New Zealand’s economy, removing cyclical variation in capacity utilisation. Even if investment expenditure varies over the business cycle in response to the availability of funds, the costs of borrowing and expectations of future sales and income can take a long time to feed into the capital stock. In addition, because capital utilisation is difficult to measure, it is generally held constant over the economic cycle by statistical agencies. The actual variation in capital utilisation will therefore appear in reported productivity. For example, in economic downturn, firms do not immediately sell capital items (unless they experience cashflow issues), so some will lie relatively idle until demand increases.

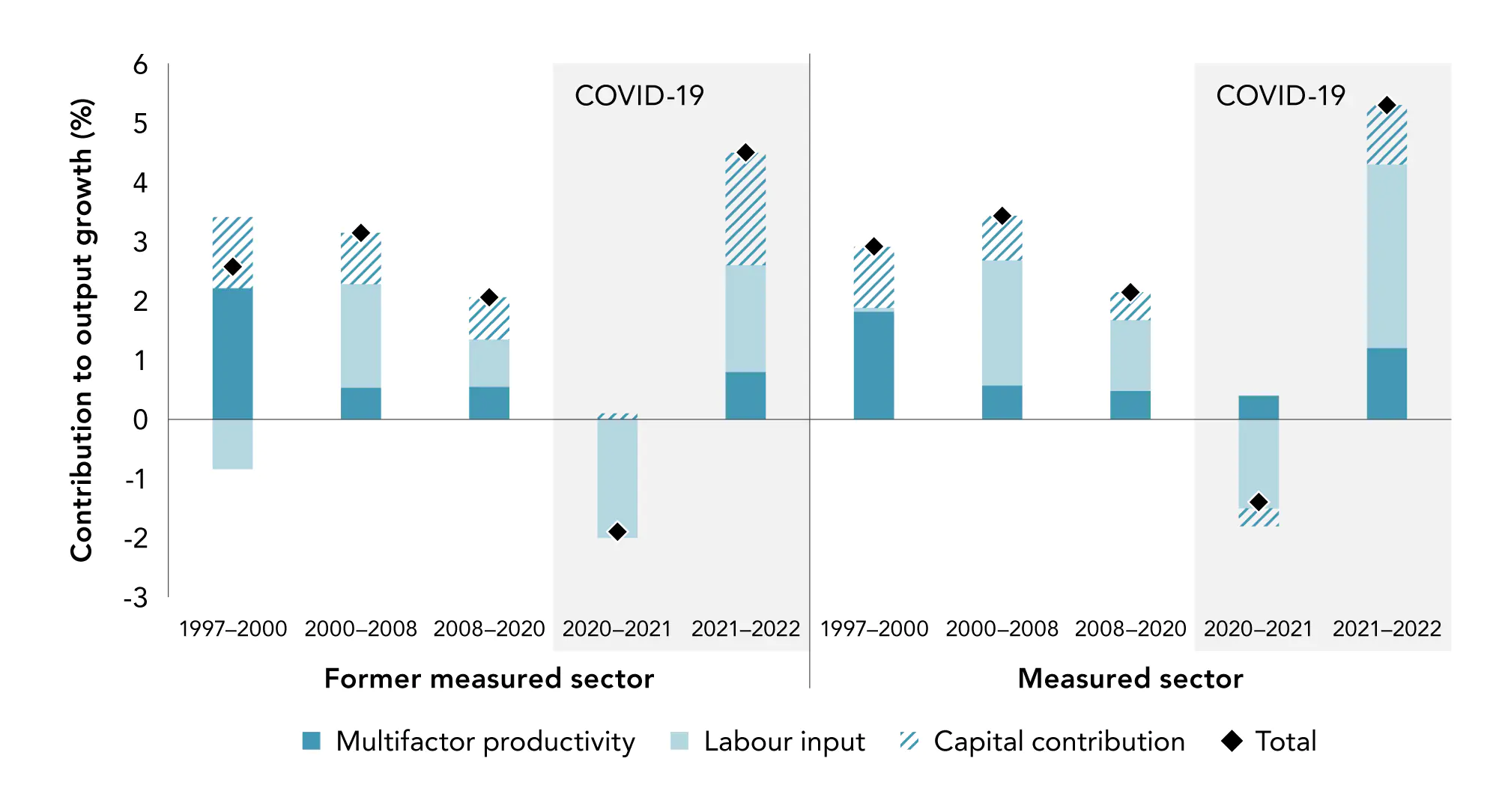

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was not like other recessions our economy has experienced. Productivity numbers are unlikely to be similar to other recessions for both economic and measurement reasons. The pandemic introduced a seismic shift to the economy and society, with long-lasting impacts on the way we work, travel, and socialise. Government interventions to minimise the economic damage of the pandemic also had an impact. This has had two major consequences. First, Stats NZ made changes to the way it calculates productivity and its components, for the statistics to be useful in the pandemic context. Second, the usual assumptions about economic behaviour did not hold. In bad times, firms with declining revenues will shrink or fail altogether. This was less likely to happen during the pandemic, due to the availability of subsidies, meaning there are a number of firms still operating that would otherwise have ceased (Bowman, 2022; McGowan et al., 2017; Pelosi et al., 2021).

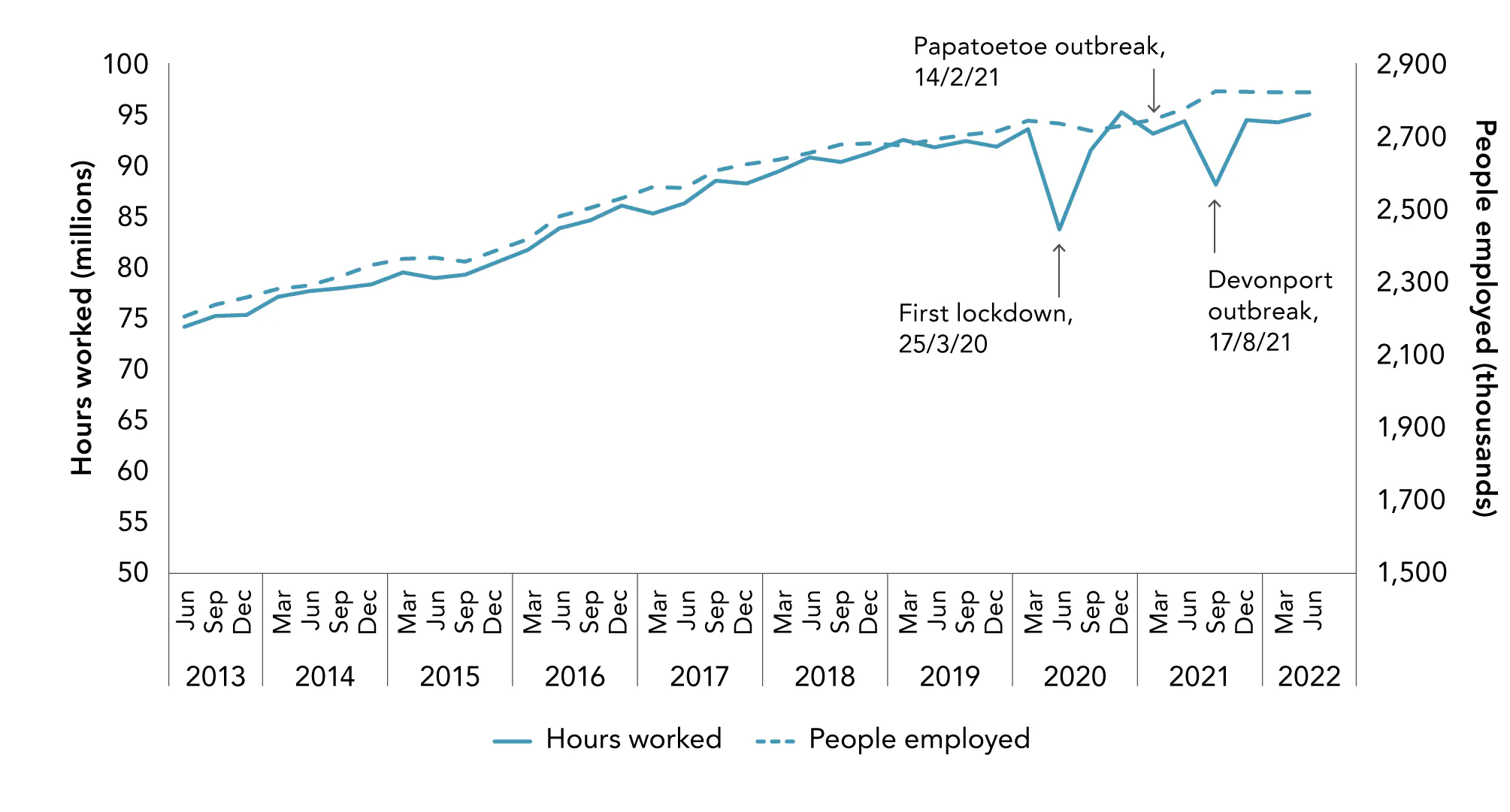

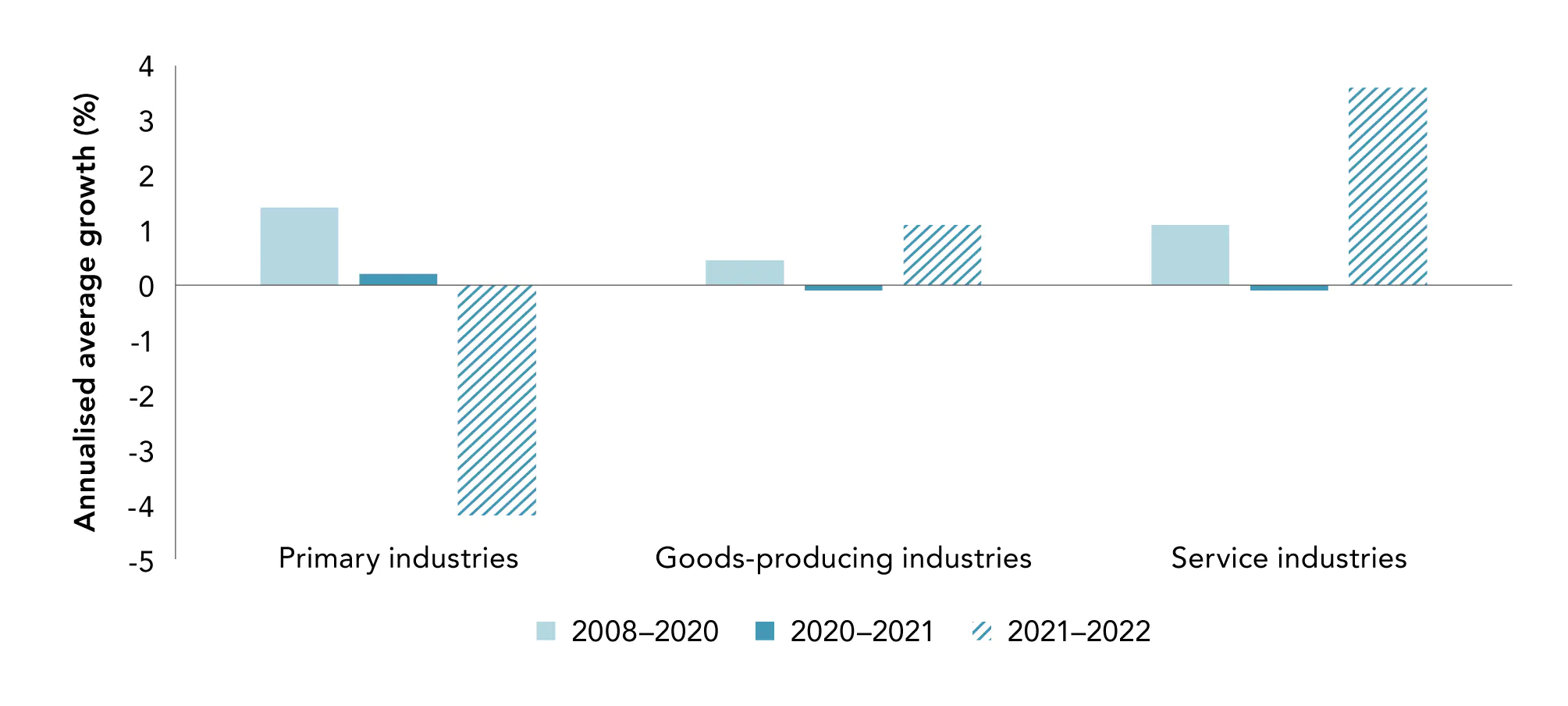

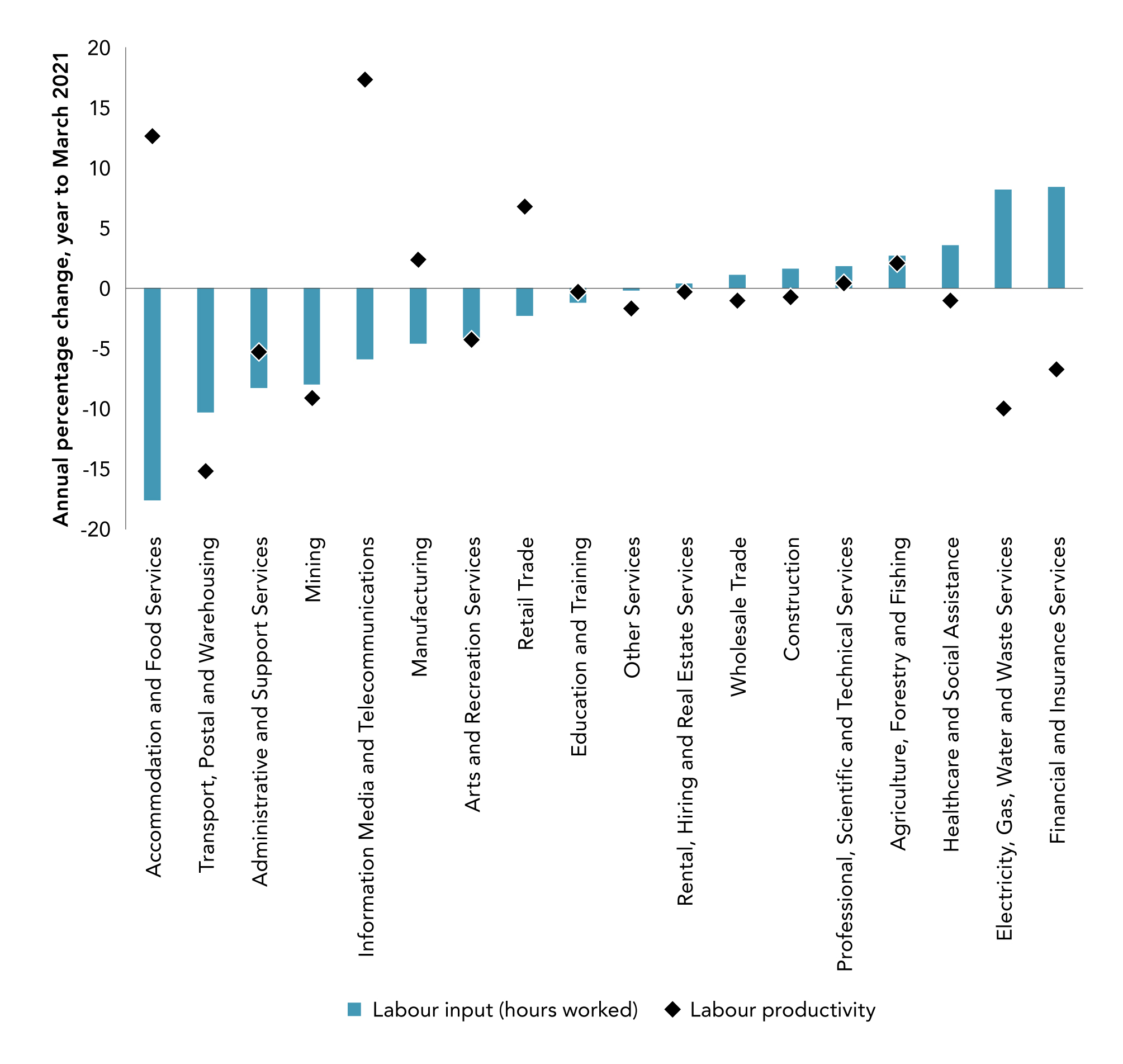

The data in the following charts go up to the year ending March 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting lockdown have been among the most economically disruptive events in recent history, with Aotearoa New Zealand’s GDP falling by the largest amount on record in the June quarter of 2020, before rebounding dramatically in the following quarter. For labour productivity, the effect of a recession depends on the extent to which firms hold on to staff during a downturn and how much firms suffer declines in output. For example, Myers, (2009) argued that, during a downturn, labour productivity growth “would be expected not to fall as much as output growth in theory because it is the least productive workers that are laid off first and the more productive workers that are retained” (p. 20). Lockdowns had different effects on businesses, depending on whether they were classed as essential services, their location, the extent to which they could continue to operate despite workers being confined to their homes, and the availability of government assistance to maintain employment relationships. As we go on to explain below, the varied effects of lockdowns meant the economic response to COVID-19 was quite different to responses to other economic shocks.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major influence on the economy

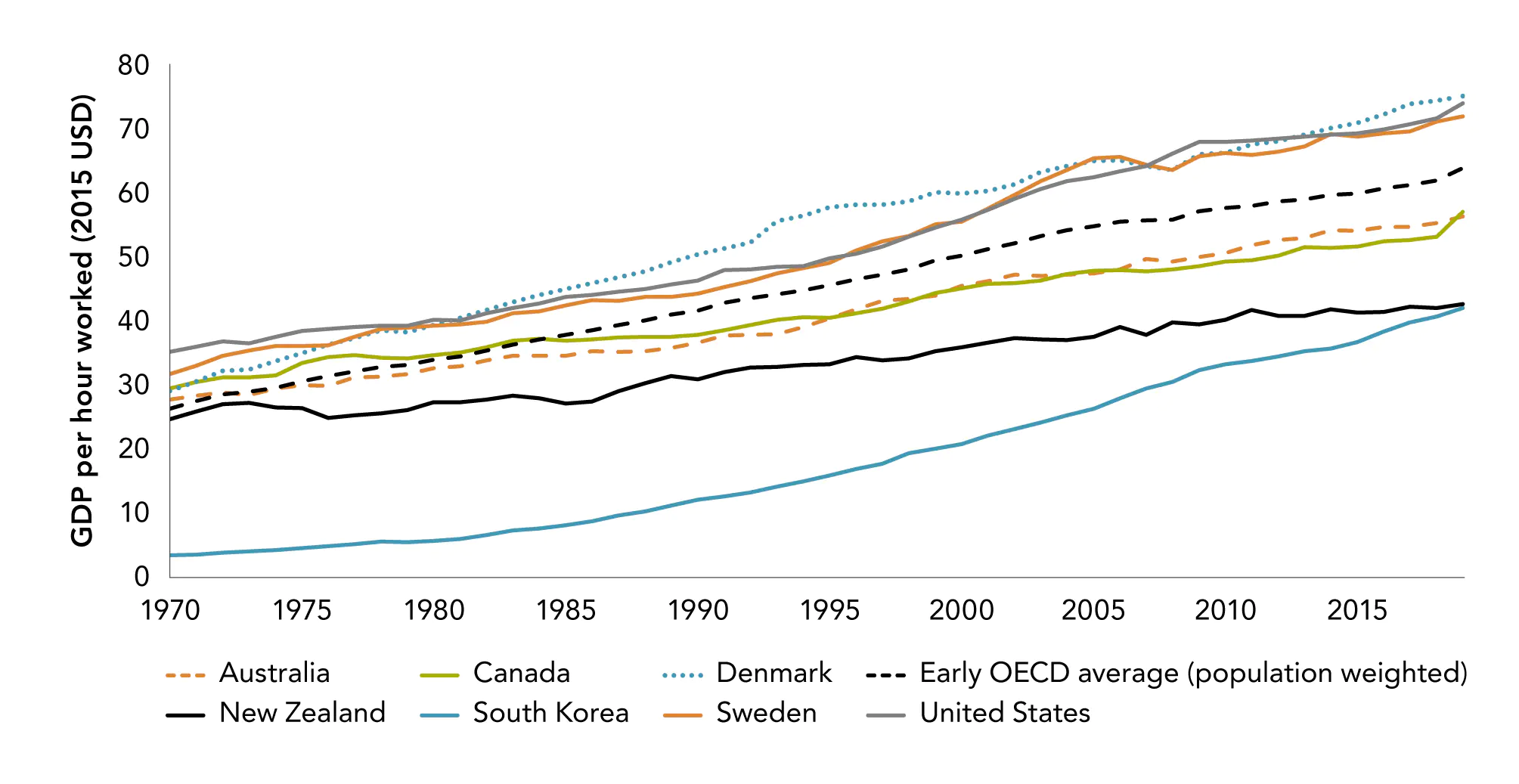

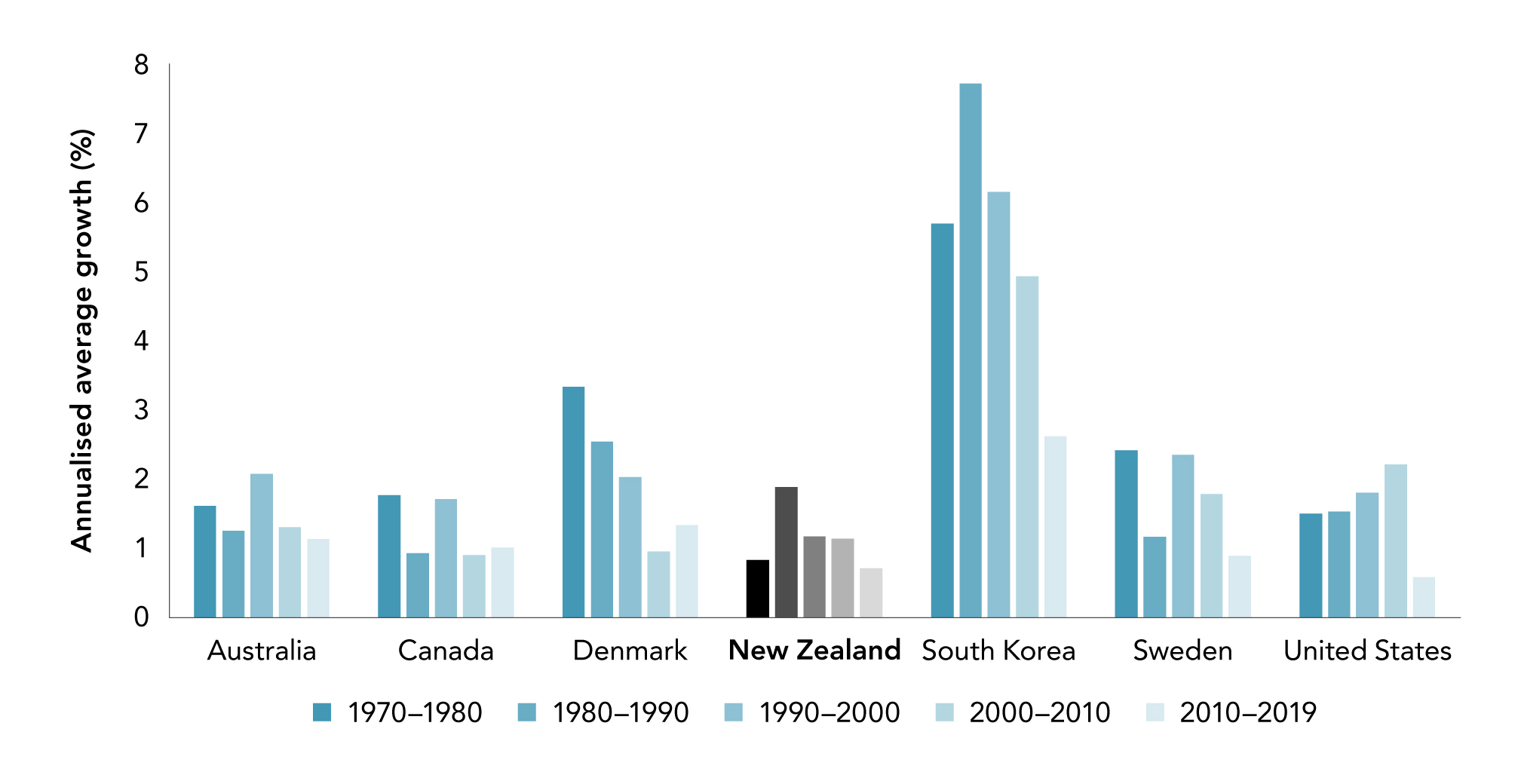

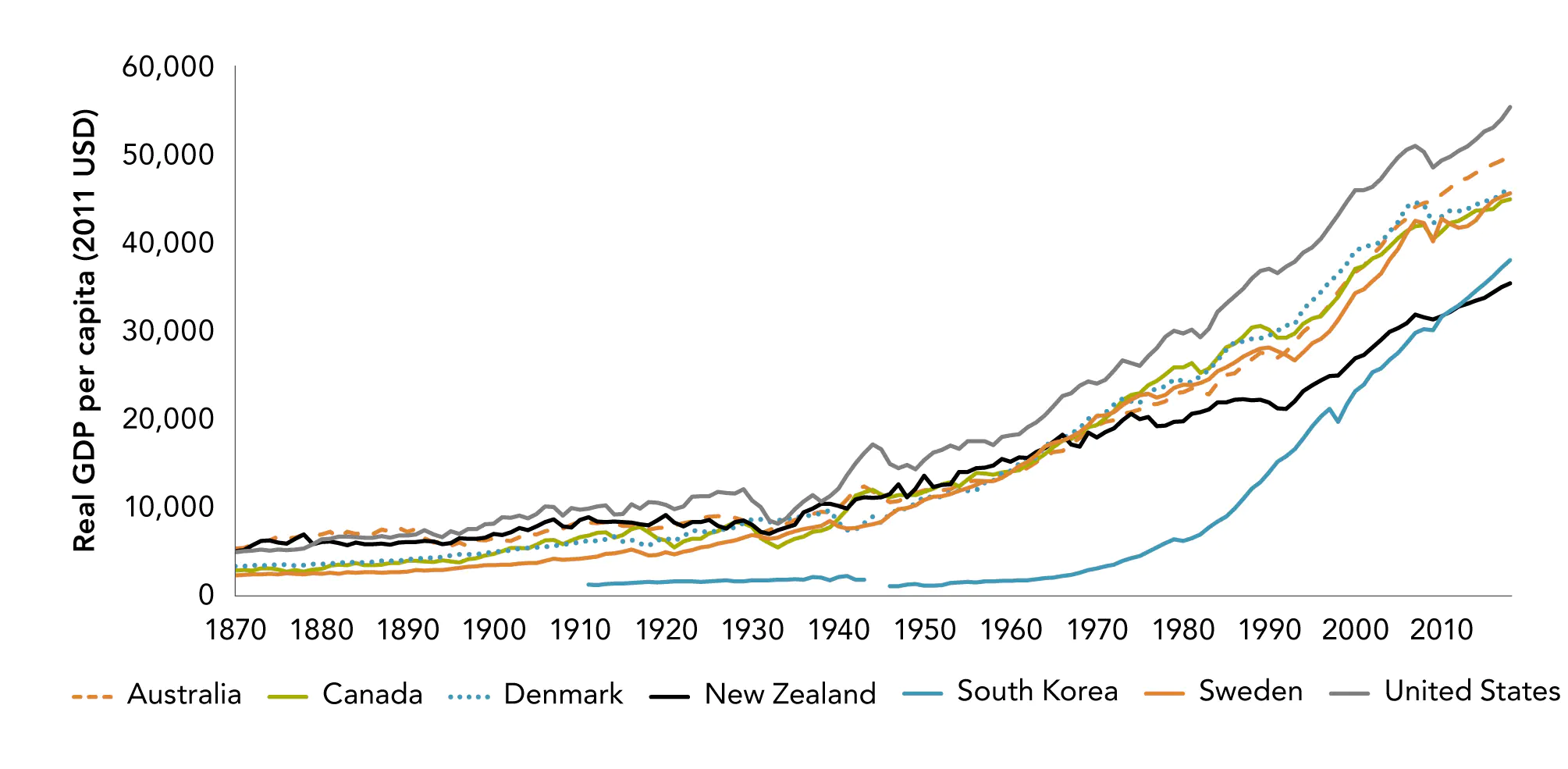

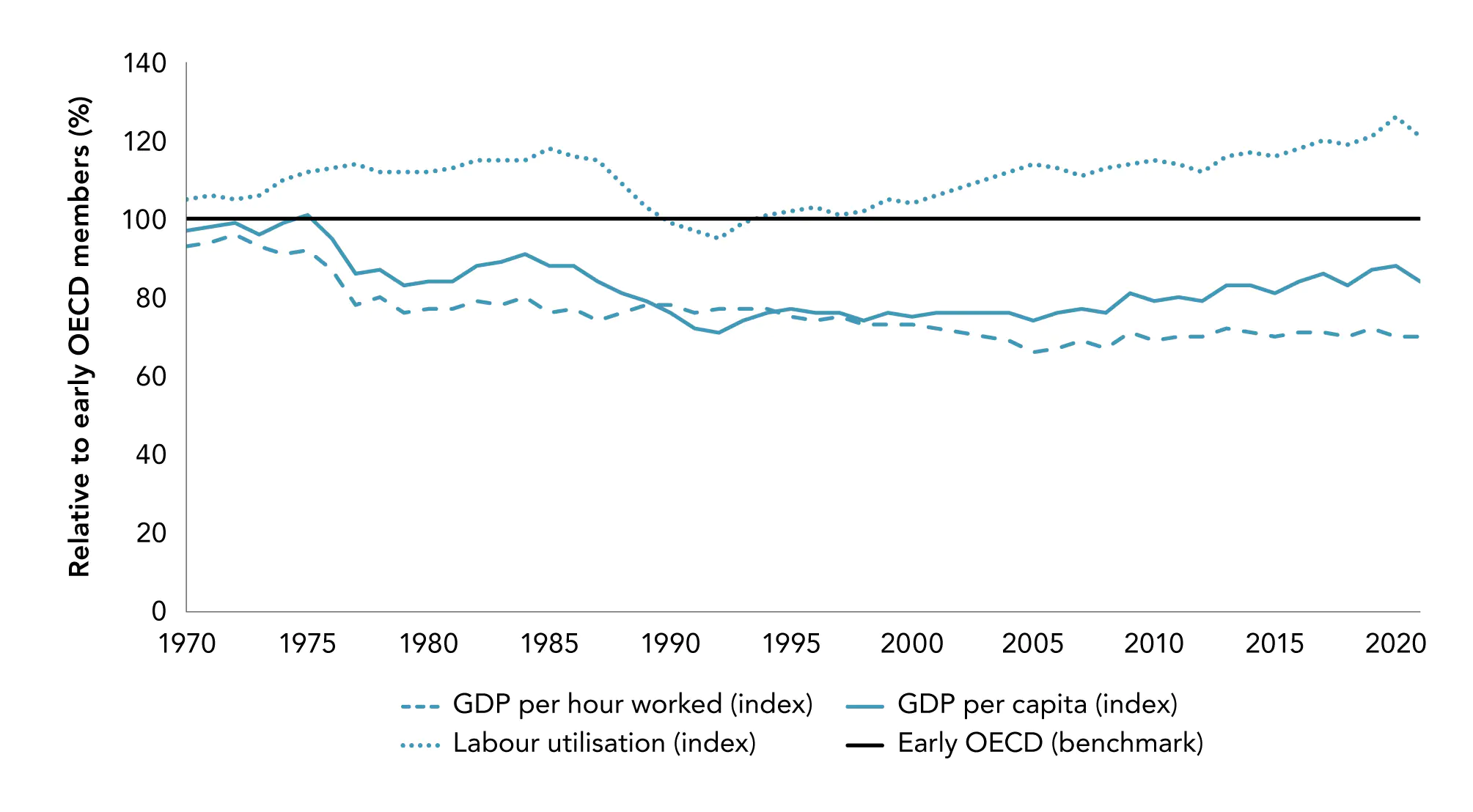

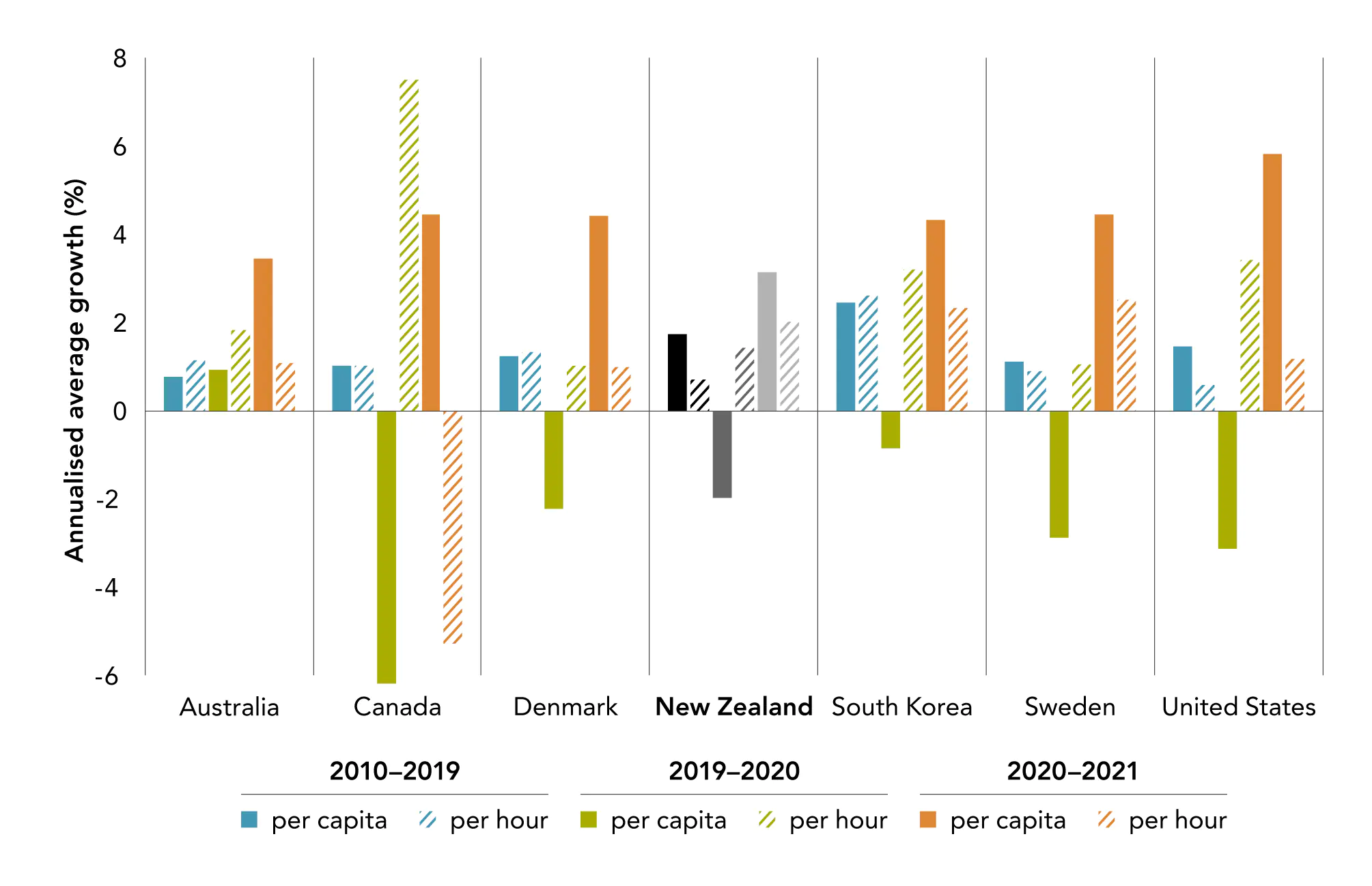

Figure 3.14 compares growth in GDP per capita and GDP per hour worked in Aotearoa New Zealand and other OECD countries. Events in 2020 were unprecedented for the entire world, and output in general was low for almost every OECD country. However, the impact of the pandemic on output per hour worked vs output per capita has been very different. During the lockdown period, labour input decreased, and capital utilisation reduced, leading to a dramatic drop in output per capita. This fall rapidly reversed in 2021, as people and firms returned to work. Both the 2020 decline and the 2021 recovery were relatively muted in New Zealand, perhaps reflecting the shorter duration of the 2020 lockdowns and the provision of government assistance to firms and workers, alongside continuing strict border controls and extended lockdowns (particularly in Auckland).

In contrast, output per hour worked remained strong in 2020, with many countries seeing growth in GDP per hour worked well above the average of the previous decade. Declining output per capita and rising output per hour was a combination of a decrease in total output and an increase in the average capacity of the remaining firms and workers. There are several reasons for this. As already noted, capital will not adjust as fast as labour, so this led to an increase in the effective capital-labour ratio within firms. In addition, as they are reducing labour input, firms will tend to reduce the hours of the least productive staff first wherever possible, increasing the average productivity of staff working. The COVID-19 pandemic experience is also a reminder that we should rely on long-term multi-year trends instead of the productivity figures for a single year.